TikTok is a digital media space born of other digital territories: its artistic genealogy comes from Musical.ly, where people lip-synched to audio clips, and its inspiration emerged from popular platforms such as Vine and Twitter, both notable for their constraints (six seconds of video and originally 140 characters, respectively). It once seemed impossible to tell a good story in 140 characters or six seconds, but micro-blogging in any medium echoes the restrictions of sonnets or haikus. Artists get creative in surprising ways when given constraints. The tools to make digital art can be financially inaccessible, and the barrier of access to communities of digital artists for those in rural or isolated places can prove challenging, but for Indigenous peoples, TikTok fills a desire for access to digital media technologies. Memes can be adopted and adapted by the pockets of Indigenous community that develop new forms of cultural knowledge.

It is in these pockets of community that TikTok’s transformative power lies. Communities like hijabi TikTok, Deaf TikTok and transboy TikTok show how less-mediated creative spaces let otherwise marginalized creators command attention. Art institutions are and have always been exclusive, only making space for a select few, but creators are taking to the digital world to mark out a different space, defying the top-down hierarchies that have defined the success of art industries. Creators riff on the same sounds from a library of audio clips and visual languages, but otherwise marginalized TikTok creators add their own spin to memes and contribute to a new language emerging from these digital spaces.

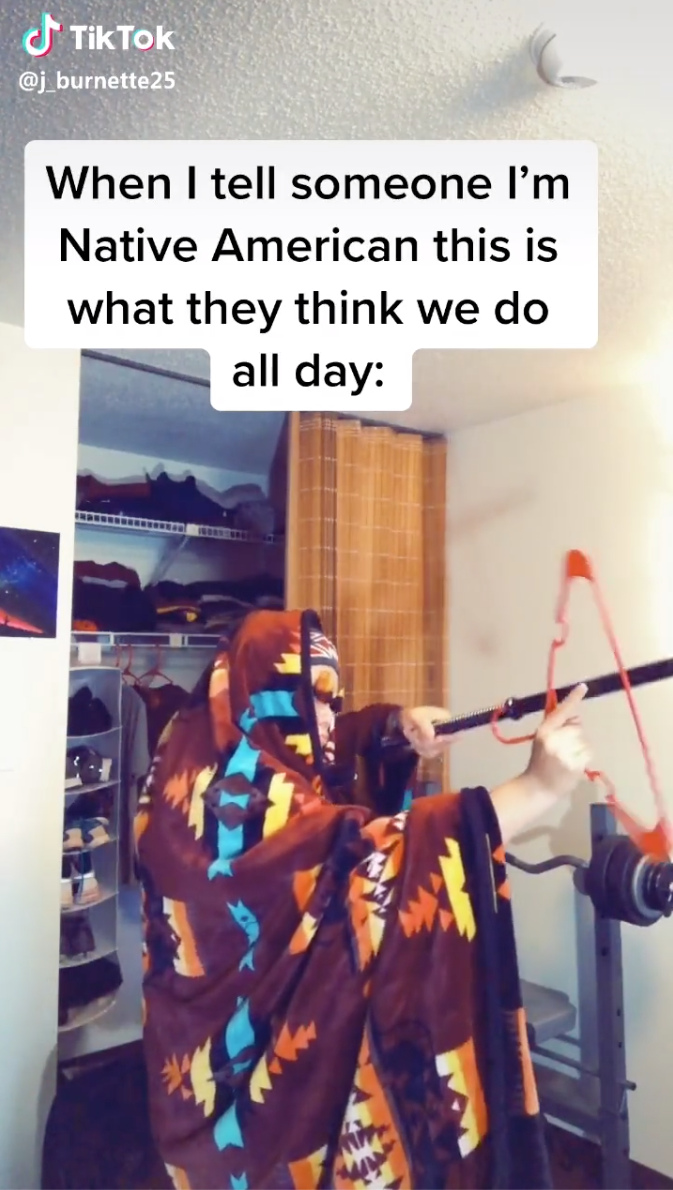

Indigenous creators on TikTok rise to the challenge as well by replicating mainstream TikTok sounds and dances with a Pendleton hanging in the background or doing popular handclapping games and trending TikTok dances in pow wow regalia. It feels revolutionary to see Indigenous representation in digital spaces. But these digital creators aren’t just content with riffing on a meme. They are taking it further than simple recitation by turning inward to express what is sometimes truly weird insider humour. NDN TikTokers are extremely aware of their audiences and how they see and are seen: they are refusing appropriation and non-Indigenous audiences through powerful forms of mutual recognition.

Of course, there are TikToks where the creators know their audience to be non-Indigenous people. They perform Indigenous cultures for voyeurs, they educate about Indigenous languages and they shrug as they list the races they’ve been mistaken for. Indigenous TikToks created for outsiders defiantly confront the way mainstream spaces see Indigenous people: disappearing, or already disappeared.

@j_burnette25, October 7, 2019.

@j_burnette25, October 7, 2019.

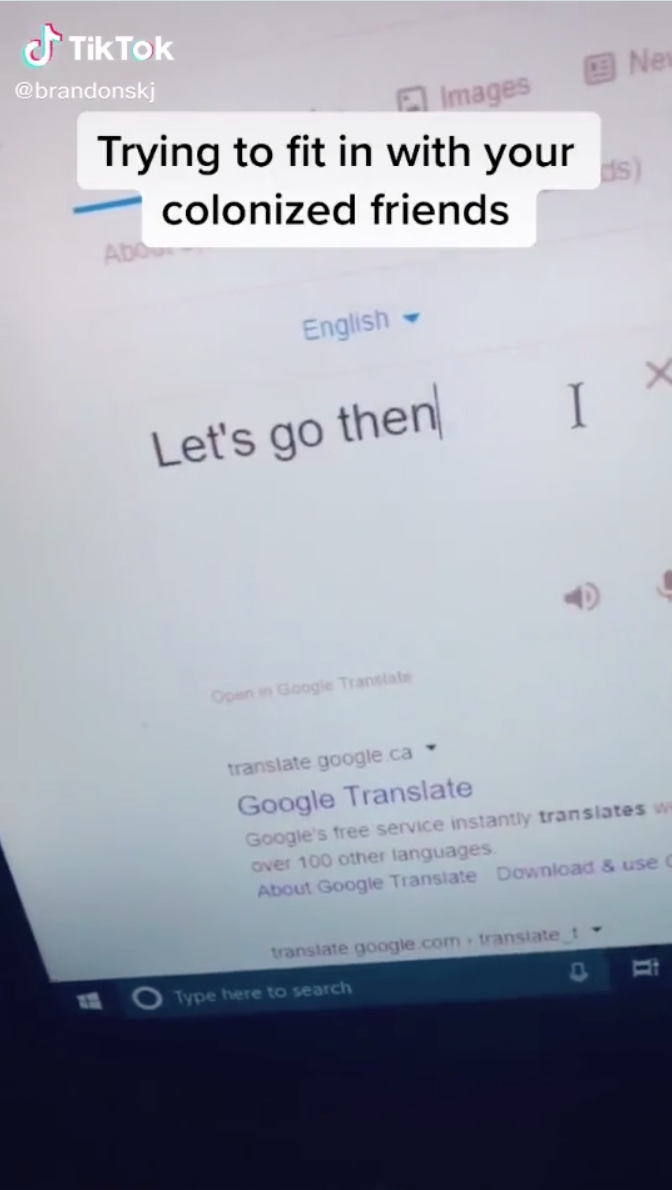

@brandonskj, February 12, 2020.

@brandonskj, February 12, 2020.

NDN TikTokers are digital creators who know their broader audiences and confront them, rather than just performing for them. NDN TikTokers are calling out racism and demanding Land Back by rallying for Wet’suwet’en. They are the makeup artists slapping a hand over their mouths to paint a red handprint, honouring murdered and missing Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit relatives. They’re calling out people wearing headdresses. They’re making fun of the way outsiders mythologize and flatten all Indigeneity. Given the nature of Indigenous youth refusal on TikTok, it should be no surprise that when the red handprint was appropriated by non-Indigenous people, NDN TikTok creators were quick to name this as theft. TikTok’s structure of repeating a sound, a dance or a meme does mean that non-Indigenous people can easily take the work created within Indigenous communities. But Indigenous creators aren’t passively allowing appropriation, either.

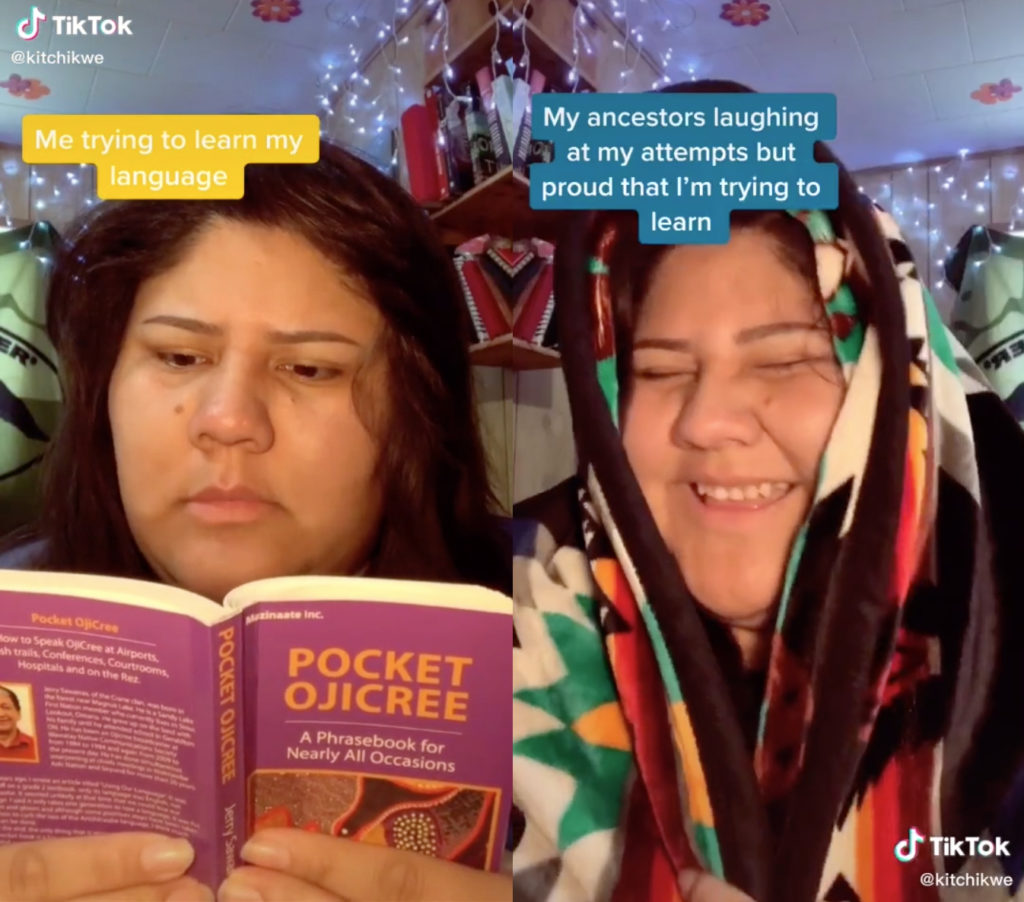

Still, the Indigenous creators on TikTok who define the innovation of NDN TikTok are those creating content largely unconcerned with outsiders. Their videos are meant to be consumed by anyone (a video might, for example, make its way to someone’s “For You” page, a constant stream of content users can infinitely scroll) but, because of in-humour and refusal, are only truly understood and enjoyed by other Indigenous people. There’s a tonal shift when NDN creators create for other Indigenous peoples—first, the relief of not having to explain history or backstory; and second, the ability to make intricate, self-referential jokes in a shared language. What is delightful about these videos is that they take on a question at the core of a recent tweet from Erica Violet Lee: Why does Indigenous presence always have to be about “resisting” and “defending”? Indigenous TikTokers who know they don’t have to perform the stoic, proud, resilient Indian to be heard are allowing themselves to be soft, funny and sweet; they are an affirmation of Indigenous life, in all its realness and silliness and intergenerational joy.

@brettstoise, February 27, 2020.

@brettstoise, February 27, 2020.

TikTok moves fast. By the time you read this, these videos will feel old, but if I were to program a small snapshot screening of the truly weird and lovely of NDN TikTok, it would certainly include spooky inside jokes about whistling at the northern lights and the goth Native aesthetic emerging across the platform. Then there are the Native takes on memes such as posing challenges, aging gookum style, the “babe stop” challenge and humorous reflections about code switching and using Native slang when around “colonized” friends. There are also powerful moments of mutual recognition, such as the struggle of being an Indigenous trans boy starting testosterone and facing the “skinny Native boy” body. TikTok is also a pocket for Native girl joy and friendship, as in this video of two cousins giving the “Rez News Report.” And I have to mention the sacred sandwich TikTok. It’s so odd! It makes no sense. It’s weirdly paced, strange and surreal, but I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it for weeks. It’s the kind of TikTok that is wholly unconcerned with an outside audience, and instead feels as though it was created just for me and other NDNs.

Digital creation for NDN TikTokers is a tool that allows their voices to be shared. Digital creation isn’t new to Indigenous art, and for Indigenous communities, adaptation is as old as frybread. NDN TikTok may look exactly like everyone else’s TikTok, using the same grammar of shared sounds and memeable poses, but Indigenous people have been so over-researched, so confined to museums and history books, that our very presence in new digital spaces feels surprising, yet welcome in its defiance.

When TikTok’s “For You” page shuffles in a video with A Tribe Called Red blasting in the background, it feels like TikTok’s algorithm, too, is exceptionally aware of its own audiences. Serendipitous discovery on TikTok is so seamless. TikTok delivers, without prompting, without following—even if a user does not have an account—a steady stream of tailored content. The platform demands interaction, forcing videos to play on loop until you swipe up. It places creators in front of you and learns from your pauses, swipes and double-taps. We delight in the repetition, humming the sounds of TikTok that get embedded in our heads and learning the dances without even really realizing it’s happening. As soon as TikTok figures out you might like Indigenous content, it adjusts and learns.

@bamb_dez88, February 27, 2020.

@bamb_dez88, February 27, 2020.

Like any digital medium, its owners are out to make money, and they’re making money from our data, our whims, our yearnings, as well as our specific hunger to have Indigenous representation in our digital spaces—what we linger on, what we laugh at and are compelled to share with our friends. All of our interactions are big business, and that should worry us.

Indigenous content creators might be aware of these privacy issues while using TikTok. But because Indigenous people are already surveilled in so many ways, they accept the risk. From Status numbers to police carding and oversight from CSIS, living joyfully even under the surveillance state seems possible because we already do it every day.

Indigenous people have been so over-researched that our very presence in new digital spaces feels surprising, yet welcome in its defiance.

Indigenous creators are constantly balancing their concerns for privacy with their need to see and be seen, and to bring Indigenous art into existence. At the core of artful existence is a deep well of joy. TikTok is a digital space that combines the visual language of Instagram, the pockets of community of early Facebook and the same immediacy that made Vines exhilarating. It should be no surprise, then, that there’s an idyllic part of TikTok, where the joy of seeing this representation creates a whole new genre of TikToks: gratitude in seeing ourselves. Indigenous creators are absolutely delighting in each other. We might be starved for representation that doesn’t commodify, appropriate or flatten us, but here, in these spaces, we’re living for each other.

On good days, my “For You” page looks like an NDN utopia. Queer NDN babies make up dances. Native moms are being loved up. There is cheeky seduction, intergenerational joy and ancestors delighting in their descendants persevering. It’s amazing the things we will risk to see and share unfettered Indigenous joy. So to all NDN TikTok, as TikToker @kidggrreegg might say, you put the wow in pow wow.

@kitchikwe, January 22, 2020.

@kitchikwe, January 22, 2020.