American cultural theorist Sianne Ngai offers an account of some “dirty words” for art and culture in our time in her 2012 book Our Aesthetic Categories, where she raises the terms “zany,” “cute” and “interesting” to the status of aesthetic concepts like the beautiful and the sublime. While these latter concepts have long been used to characterize our disinterested engagement with artworks, Ngai’s categories form a new critical vocabulary bound to the often self-interested, or at least purposeful, activities of consuming, labouring and exchanging. The cute is Ngai’s aesthetic of powerlessness, reflecting our predatory relationship with commodities; the zany is associated with emotional labour and the performance-driven conditions of the workplace; and the interesting is connected to the information economy and its sprawling networks of exchange. Besides gathering an awful lot of cultural material in their nets, these terms warn us about the ills of late capitalism: accumulating endlessly, smiling on command and scrolling, sorting and bookmarking until our eyes bleed.

Of Ngai’s three key words, the interesting is surely the most frequently invoked in contemporary art discourse. We could blame Conceptualism: in a legendary 1971 project, American artist John Baldessari sent instructions to a group of students at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design to write “I will not make any more boring art” on the walls of the school’s Mezzanine Gallery. Now, “interesting” and “interested in” are overused in artists’ talks, where they serve a gathering function (“I was interested in x, y and z…”) or mark a change of course (“…and then I became interested in object-oriented ontology!”). In polite vernissage conversation, “interesting” hangs ambivalently in the air between sincere praise and a kiss of death.

For Ngai, the interesting does indeed have roots in Conceptual art from the 1960s and ’70s, primarily its cool, detached attitude, recursive or ongoing temporality and neutral modes of presentation. However, “interesting” also flirts with boredom and risks becoming “merely interesting,” a phrase Ngai adopts from Michael Fried’s landmark critique of Minimalism, “Art and Objecthood.” When we say something is interesting, she argues, it’s because we’ve picked out a novelty against a “backdrop of the expected and familiar,” such as the lone image of a glass of milk in Ed Ruscha’s artist’s book Various Small Fires and Milk (1964). Other Conceptual artists add personal and political dimensions to this category. Baldessari’s photo series A Person Was Asked to Point (1969) and his Commissioned Paintings (1969) attach a physical gesture to the aesthetic. For Ngai, we point out what’s interesting, idiosyncratically, and thennominate it more publicly as a work of art. Of course, whether or not we acknowledge the nomination of merely interesting things as art sometimes depends simply on who is doing the pointing. However it comes about, by identifying an object or observation as interesting, we create a space in conversation to test our reasons for the judgment.

Thirteen years after Baldessari sent his orders to those students in Halifax, Toronto artist Micah Lexier graduated from NSCAD with an MFA. To this day, Lexier seems to have internalized the point of that earlier lesson. “I think my work is firmly rooted in Conceptualism,” says Lexier of his artistic practice. “I love all its tropes and strategies, but I am not bound to them.… I take what I love about it and mix it with what is interesting me at the time.” Among his interests he lists handwriting, signage, found imagery, portraiture, line drawings and letters. But other items on his list break the mould, such as simplicity, everyday, the passage of time, and family. In effect, Lexier’s work engages the merely interesting as a means of identifying patterns and organizing information to relay more abiding interests in interpersonal relationships, aging and community.

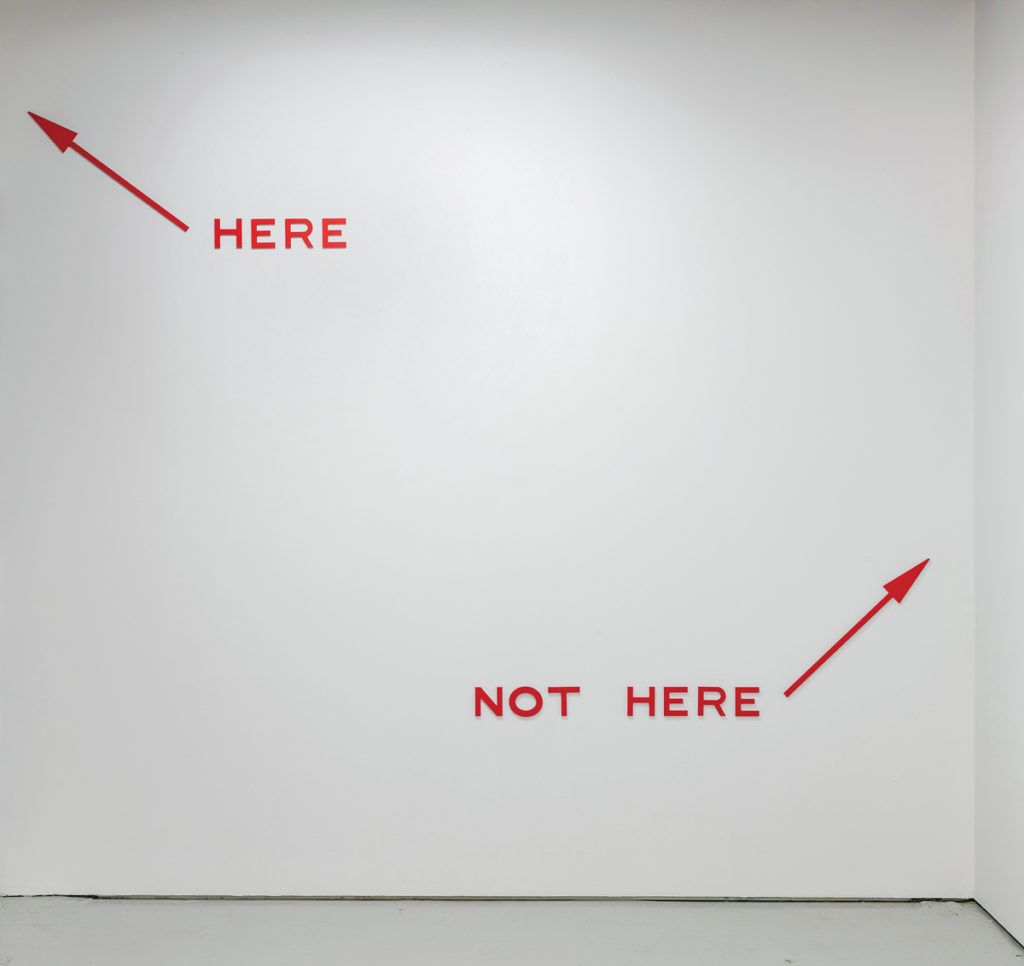

Lexier’s latest body of work offers a case in point. “Here, Not Here,” a solo exhibition on view last fall at Birch Contemporary in Toronto, included four pairs of aluminum arrows (a recurring motif for Lexier) painted in discrete colours and installed on the gallery walls. Each arrow was accompanied by the seemingly arbitrary block-letter directive to look or move “HERE” but “NOT HERE.” In the back gallery, another set of wall-mounted works featured pairs of drawings in acid-etched stainless steel of domino shapes stacked in subtly varied configurations. A small arrow points to one of the dominoes as it changes position between the two drawings, as if in a game of spot the difference. What at first looks like a series of merely interesting diversions turns into a deeply interesting, even cautionary, meditation on vulnerability and dissimulation. The works are based on found images: a photo from a Second World War camouflage manual indicating safe and exposed positions, and an instructional drawing for a game of dominoes.

The deliberateness of Lexier’s placement of each element in the exhibition is interesting, which is to say that, in Ngai’s terms, differences begin to stand out against a background of sameness the longer one looks at the work. The moving domino in each drawing has a mysterious raison d’être, a conspicuous individuality that the other fixed pieces don’t. As the arrows direct viewers to one side or the other of a corner in the front gallery, the banal architectural detail of a right angle begins to take on the character of a moral boundary. These considered tweaks display Lexier’s meticulous sense of material and design, but the work is even more durably interesting than this. In conversation with Lexier, I learned that the interests of various communities were part of the decision-making behind the exhibition, in its plays of appearance and disappearance, standing and falling. While he dislikes being pigeonholed by any one label, Lexier agreed that his work captures anxieties about death and survival in his own gay, Jewish and artist communities.

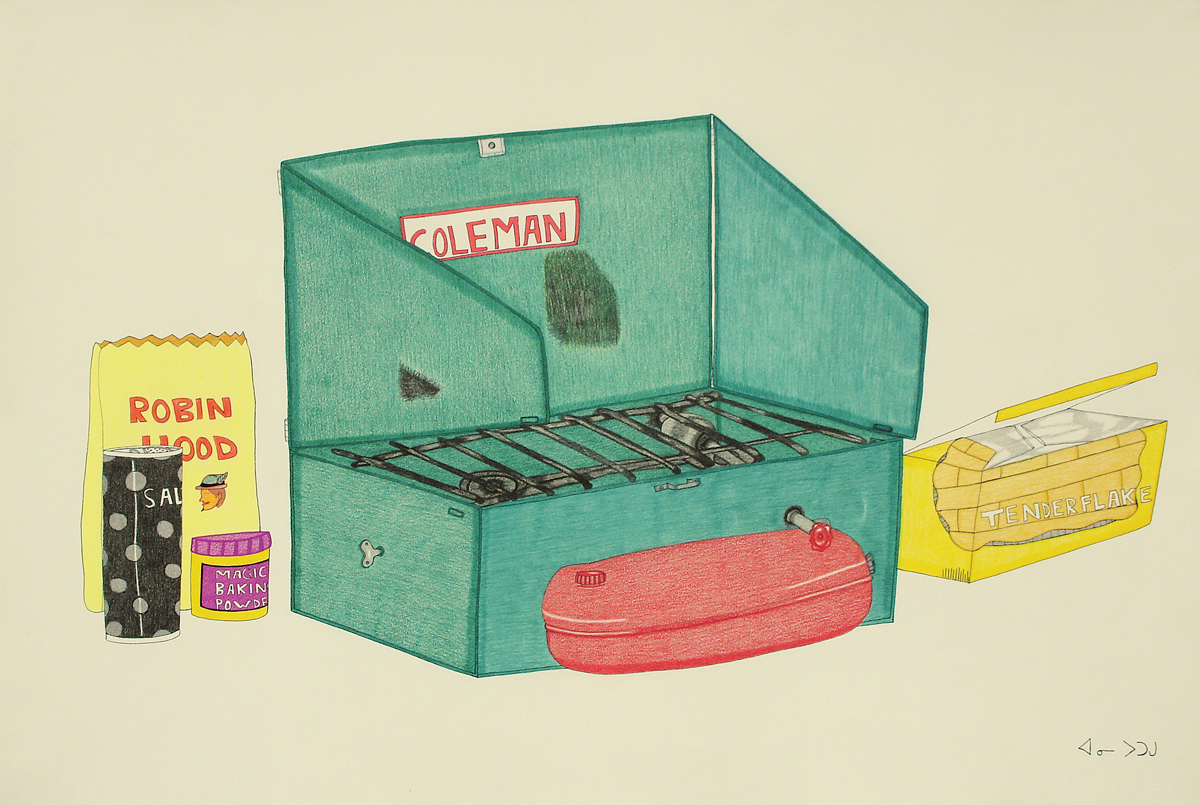

Annie Pootoogook, Coleman Stove with Robin Hood Flour and Tenderflake, 2003–04. Pencil crayon and ink, 76.2 cm x 1.12 m. Courtesy Feheley Fine Arts. Copyright Dorset Fine Arts.

Annie Pootoogook, Coleman Stove with Robin Hood Flour and Tenderflake, 2003–04. Pencil crayon and ink, 76.2 cm x 1.12 m. Courtesy Feheley Fine Arts. Copyright Dorset Fine Arts.

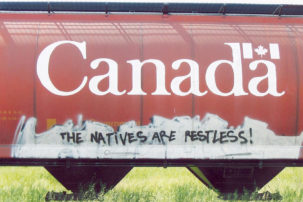

What is interesting about Conceptual art for many of its practitioners since the 1960s is how it aligns with clearly stated political interests. Conceptualism has been taken up in a vital way by artists with explicitly identity-political aims. In the curatorial thinking behind Wood Land School’s “Kahatenhstánion tsi na’tetiatere ne Iotohrkó:wa tánon Iotohrha / Drawing Lines from January to December” at SBC Gallery of Contemporary Art in Montreal, Conceptualist devices were used to make claims (to land, to traditions and to a sovereign future) in the interests of Indigenous peoples. The project engaged three notable features of Conceptualism, or the aesthetic of the interesting: its use of text and documentation, its ongoing or recursive temporality, and its claim-making effect of expanding a public sphere for contemporary art. Details of the works and attitudes of the artists in the project stand out as willed differences against a monotonous background of settler colonial representations of indigeneity.

Organized by artists Duane Linklater and Tanya Lukin Linklater, along with curator cheyanne turions and artist Walter Scott, the Wood Land School project was a year-long exhibition comprised of four parts or “gestures.” The late Inuk artist Annie Pootoogook’s Coleman Stove with Robin Hood Flour and Tenderflake (2003–04) served as the conceptual anchor for the exhibition, remaining on display for its entire duration. In the drawing, Pootoogook depicts what could be considered the merely interesting ingredients and appliances used for making bannock. Within the drawing’s symbolic nexus, however, the organizers’ deeper interests in mobility and becoming as elements of an “Indigenous futurity” are expressed. Pootoogook presents these ingredients for future use. For the organizers, the work metaphorically points ahead to the ongoing project of Indigenous self-determination. The fact that the stove is portable suggests the importance of pursuing the Indigenous community’s interests wherever they are undermined, on both sides of the Canada-US border, where the exhibition’s participants live and work.

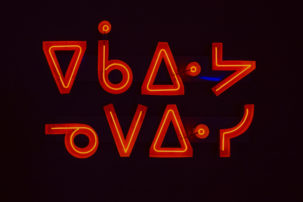

In the exhibition’s second gesture, Joi T. Arcand’s neon channel sign ᐁᑳᐏᔭ ᓀᐯᐃᐧᓯ (e¯ka¯wiya ne¯pe¯wisi) (2017) presents language as a medium of communication between Indigenous persons, but also as a potential tool for coalition-building outside of the Indigenous community. The wash of pink neon light from Arcand’s sign is familiar at a glance. One recognizes the look of the sign from shopping malls and commercial strips, or, for contemporary art initiates, it recalls the work of Conceptualists and Minimalists like Dan Flavin and Bruce Nauman. These points of reference draw the viewer in even if the sign’s Plains Cree syllabics remain inaccessible. The translation of the sign, “Don’t be shy,” can be read as an invitation for Indigenous and non-Indigenous viewers alike to assist in bringing about the future Arcand envisions, by engaging in conversations about self-determination, mutual accountability and stewardship of land.

Also in the second gesture, Wendy Red Star’s black-and-white poster of an all-Crow rock band titled The Maniacs (We’re Not The Best But We’re Better Than The Rest) (2017) utilizes the Conceptualist form of the photo document. The exhibition notes stress the importance of the band for their fans: “White people had the Beatles, and we [Crow Indians] had the Maniacs.” The band’s look recalls the Beatles in their clean-cut pre–Sgt. Pepper’s period, and the home-studio setting of the image might just as well have been from the band’s own Lodge Grass, Montana, reservation or from a nearby town where the band members endured “racial tensions between white farmers and Native people.” One notes the striking difference race makes in the poster (as it did in the band’s career) against a background of familiar markers of rock music subculture.

This disturbance in the photo is key to its interest. For turions, Conceptualist devices like this one seek to challenge or “interrupt” a taken-for-granted historical record. When asked about the influence of Conceptualism in the Wood Land School project, turions remarked that the exhibition was “as much about the intellectual space that it claimed and the histories it interrupted as it was about the objects in the gallery.”

Struggles against settler colonial violence are also at the centre of the work of Montreal-based Palestinian artist Muhammad Nour Elkhairy. In his text-based, four-minute video work I Would Like to Visit (2016), Elkhairy employs the cool, minimal aesthetic of what Ngai would call the merely interesting as an alternative to more dramatic representations of Palestinian victimhood. While it is difficult for Palestinians in the diaspora to occupy a neutral political position, the aesthetics of the interesting in Conceptual art offer an appearance of neutrality that Elkhairy directs toward political ends. The piece begins and ends with a simple sentence on a computer screen: “I would like to visit Israel.”

In between these moments, a deeply conflicted text is cobbled together out of qualifiers, refinements and second-guesses. The original statement of desire is thwarted by a series of logistical and moral obstacles to its fulfillment. Elkhairy could visit the “apartheid state of Israel” if he possessed a North American passport, he reasons, making himself a settler on colonized land. The last line typed before the entire text is highlighted and then swiftly deleted reads, “I may be granted a visit visa, If I erase any visible political affiliations and beliefs I have and appear neutral.” If Lexier abstracts merely interesting elements from a politically charged military photo, Elkhairy returns us to a battleground of conflicting interests.

Elkhairy creates an unresolved, looping text that conveys the experience of waiting endlessly in exile. The Conceptualist ruse in this case calls a diasporic public sphere into being from settler colonial states in North America and the Middle East. Like the Wood Land School project, which ultimately aims at coalition-building in Canada and across the US border, Elkhairy’s work envisions a “global Indigenous solidarity.”

The art historian Lucy Lippard worried in the 1970s about a loss of political power for Conceptual art, a power that seemed to her to depend on the feminist, anti-corporatist, anti-racist interests of its earliest proponents, and its resistance to commodification. Conceptualism became merely interesting, rather than vitally of interest. The artists of the Wood Land School gestures and Elkhairy carry on this critical tradition, repositioning Conceptualism as an art of publicly oriented ideas rather than privately coveted things. In both cases, the stylistic features of their works are perfectly attuned to historical experiences of dematerialization that continue to hold urgent political, as well as aesthetic, interest.

Tammer El-Sheikh is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Fine Arts at Concordia University in Montreal. His writing on contemporary art has appeared in Parachute, ETC and C Magazine, among others. This post adapted from the article “Interesting” in Canadian Art‘s Spring 2018 issue, which is themed on “Dirty Words.”

Micah Lexier, Here, Not Here (Red) (detail), 2017. Waterjet-cut 1/4-inch aluminum and enamel paint, dimensions variable. Collection Szafranski, Calgary. Courtesy Birch Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Micah Lexier, Here, Not Here (Red) (detail), 2017. Waterjet-cut 1/4-inch aluminum and enamel paint, dimensions variable. Collection Szafranski, Calgary. Courtesy Birch Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.