This year, as Montreal’s 375th anniversary coincided with the 150th anniversary of Canadian confederation, the city doubled down on its efforts to reinforce a national narrative. Amid the colonial fanfare, now-former Mayor Denis Coderre spent a reported $39.5 million to illuminate the Jacques Cartier Bridge as a birthday gift to the city. The art that stood out to me throughout the year was work that resisted the nation-building project, and offered both critique and a space for decolonial reimaginings.

Two-Spirit Sur-Thrivance and the Art of Interrupting Narrative at Never Apart

Curated by Jeffrey McNeil-Seymour and Michael Venus, “Two-Spirit Sur-Thrivance and the Art of Interrupting Narratives” featured Two-Spirit artists from across the country. The exhibition aimed to disrupt colonial narratives by re-centring Two-Spirit voices within the discourses of reconciliation and settler queerness.

Featured in the show were prints, preparatory sketches and sculptures by Kent Monkman, as well as photography, video and beadwork by Dayna Danger, both of whom employed camp and the visual lexicon of kink. Their work was playful with an erotic charge, an intimacy created by the taboo public display of sculptural sex toys and fetish gear, such as Danger’s beaded and black leather BDSM masks, or Monkman’s Miss Chief’s Praying Hands (Red) (2016).

Preston Buffalo’s self-portraiture challenged the colonial gaze and put viewers into direct, one-on-one conversation with the image of the artist to confront a legacy of anti-Indigenous violence and erasure. In Toile Face, for example, Buffalo made direct eye contact with the viewer, his floating face superimposed with red toile.

Fallon Simard’s video pieces digitally animated photographs taken by the artist’s mother to grapple with the displacement and dissociation caused by colonial disruptions to land. The initial photograph in Mercury Poisoning (2016) showed the shoreline of Couchiching First Nation, the artist’s home territory, where the lake is continually poisoned by mercury from a nearby paper mill. As the video unfolded, the photograph became distorted beyond recognition, the initial shot warped by blotches of colour like an oil slick.

As a response to Metis artist Jaime Black’s REDress Project, Jeffrey McNeil-Seymour’s Unsettl(er)ing offered space for reflection about the ongoing violence faced by Indigenous women. Through subtle gendered codes, the work critiqued the ways in which the use of colonial paradigms of gender and sexuality within discourses of murdered and missing Indigenous women often erases the lived realities (and violence) faced by Indigenous trans women and Two-Spirit people. In this piece, a map of Indigenous nations in Turtle Island was overlaid with a red dress made from a gauzy, translucent material that hung near eye-level. I was constantly aware of my body’s relation to the dress, which fuelled a reckoning of my own position as a Black queer subject in Canada, the ways in which I am complicit in colonial violence and the erasure of Two-Spirit identities, and how I might use my position to foster Black Indigenous solidarity.

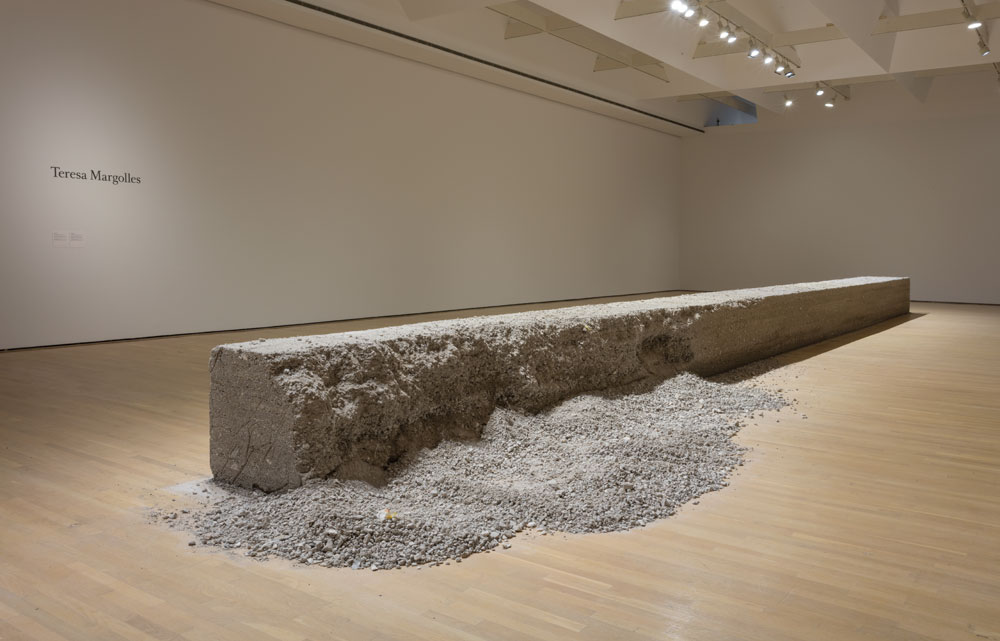

Teresa Margolles, La Promesa (The Promise), 2012. Sculptural block made of ground-up remains from a demolished house in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, 15-tonne version, 73 x 80 x 1600 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

Teresa Margolles, La Promesa (The Promise), 2012. Sculptural block made of ground-up remains from a demolished house in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, 15-tonne version, 73 x 80 x 1600 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

Mundos at the Musée d’art contemporain

Another exhibition that commanded my attention this year was Teresa Margolles’s solo show “Mundos” at the MAC. With a body of work that spans decades, Margolles is one of Mexico’s most prominent contemporary artists, and this show marked her first major museum exhibition in Canada. Largely a response to the institutional neglect and state violence in the Northern Mexican border town of Ciudad Juarez, “Mundos” included installation and sculptural work, video, photography, and performance, most of which Margolles made within the last decade.

Many of Margolles’s pieces played with scale, which rendered the marginal too large to ignore. In Pesquisas, Margolles created a haunting portrait of the ongoing femicide in Ciudad Juarez, which has been sanctioned by willful ignorance and perpetuated by state inaction. In this piece, the artist photographed posters of missing women she found on the streets of Ciudad Juarez from the late 1990s to present day, many of the them torn or rendered illegible due to years of damage and neglect. Thirty of these posters, blown up, were placed across an entire gallery wall.

In the large-scale photographic series Pistas de Baile, trans sex workers stand among the remains of various demolished nightclubs in Ciudad Juarez, ones that have been torn down in the wake of renewed development interest in the city’s downtown. The women in these photographs confront the viewer’s gaze. They assert their presence in a landscape in which they face increased marginalization, their workspaces bulldozed in the name of urban renewal. On the floor of the gallery sat a six-metre long neon sign from Mundos, a former nightclub from which the exhibition takes its name, its glow and hum in the otherwise quiet gallery a reminder of resilience.

La Promesa, a performance piece situated around a 16-metre long sculptural wall, called attention to the interplay between border control and international trade that exploited and then displaced Ciudad Juarez’s working class. The wall was constructed from 22 tons of debris collected from an abandoned house in a development in Ciudad Juarez. That site was home to thousands of people who migrated to the city to work at factories that assembled tariff-free exports to the United States. Many of these factory workers were subsequently forced to leave Ciudad Juarez due to the continual threat of violence. As an intervention throughout the exhibition’s run, volunteers chipped away at the wall daily and dispersed the rubble across the museum floor. By the time I saw La Promesa in early May, the wall had been chipped away significantly, the air thick with a dust that would not settle.

La Foret Noire at the MAI (Montreal, arts interculturels)

I stumbled into Anna Jane McIntyre’s “La Foret Noire” at the MAI by chance when I attended a writing workshop that took place within the exhibition. A gallery may sound like a sterile setting for a writing workshop, but Anna Jane McIntyre’s multimedia installation reanimated the space into a lush and imaginative landscape. The complexity and care with which McIntyre braided together disparate cultural artifacts in her work felt particularly important in a year in which Black and Indigenous communities, refugees and new immigrants, and Muslim communities (specifically Muslim women) faced increasing hostility in Montreal. In the face of such hostility, McIntyre’s work provided possibilities for the formation of new coalitions.

I visited “La Foret Noire” again a few days after the writing workshop and allowed myself to get lost in its imaginings once more. The exhibition “La Foret Noire” was culled from a mixture of Trinidadian, British and Canadian influences, ephemera, imagery and folklore. Long gauzy banners hung from the ceiling, each printed with the black silhouette of a child-like rendering of a tree with branches and leaves that sprouted from thick trunks in every direction. A small cabin, with a lamp-lit interior and a tricycle parked at the door, housed puppets, dolls, trinkets and a bed of colourful quilts. The theatrical design of the space begged for narrative, but a clear one was tactfully evaded. McIntyre left clues for viewers to pick up: a handmade doll, a broom propped against a wooden chair, a wind chime hung to dangle from a cabin roof. These clues didn’t lead to a single narrative, which granted the exhibition an elusive quality that spoke to the multilayered nature of mixed identities, migration and diaspora.

Cason Sharpe is a writer based in Montreal. He is the author of the collection Our Lady of Perpetual Realness and Other Stories.

A view of the Teresa Margolles exhibition “Mundos” at the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal.

A view of the Teresa Margolles exhibition “Mundos” at the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal.