My inspirations are woven carpets depicting gardens with great mastery. Centuries or millennia old, these are far from romanticized landscapes: they suggest balanced microcosms with flora, fauna, myths and legends of their specific times. And here, looking out through large glass windows of my studio, is my own garden, shaped over 18 years’ labour. I have a chance here to contemplate the landscape in every season—see birds moving, cats hunting, deer visiting. I have a small greenhouse to help lengthen the short growing season.

The foundation of my gardening practice is what I brought from Hungary when I immigrated to Canada in 1988. When I work on the land, I am inspired by my ancestors’ farmer lives, their hunger to grow food. When I was young, I loved biology and used to picture myself in a research lab making new discoveries with plants, cells, molecules and genes. My life made different turns, however. Instead of being a scientist, I now, at 68 years of age, earn my living as an independent visual artist—and I also became a gardener. Is there such a thing as just “becoming” a gardener, though? At root, I have an obsession for horticulture: tree-planting and food-growing. I like to visit great gardens, real and virtual. I exchange seeds and ideas locally and visit botanical gardens internationally, taking pictures, making drawings from this subject all the time. Gardening comes close to my professional artistic life in subject and scale. At this point I would not know, really, which comes first.

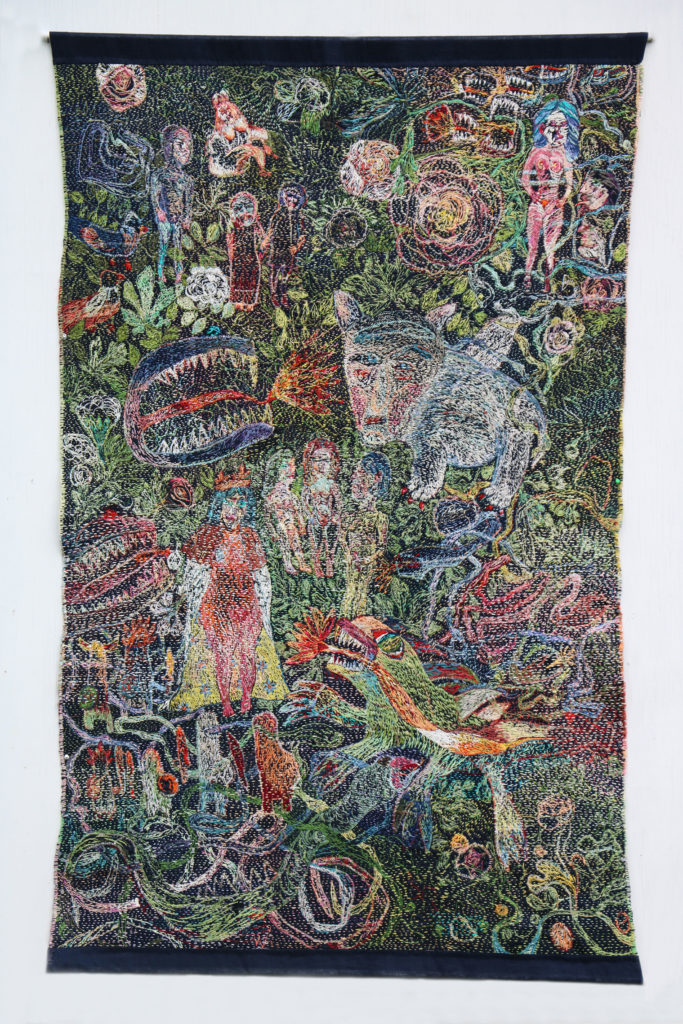

Anna Torma, Permanent Danger, 2017. Hand embroidery on linen, 2.06 x 1.25 m. Photo: Istvan Zsako.

Anna Torma, Permanent Danger, 2017. Hand embroidery on linen, 2.06 x 1.25 m. Photo: Istvan Zsako.

My garden contains three equally important parts, connected by a walkway network. Each part is approximately two acres: The first part is the undisturbed territory of wildlife, that which we do not visit often. Our 18 years of presence here is enough time to see the change, to see how the previously domesticated area became bushland, then a forest with spruces, white pines, silver poplars and birches. It is a reverse action to the early settlers’ “clearing” of the land. The second part is a meadow with a small creek. Green lawn patches, mowed a few times a year, marshland trees and bushes make the scenery. This rich place gives us a chance to hear birds and frogs, meet bees and other insects—the little helpers. Pollinators love the wildflower meadow, full of goldenrod, dandelion and other plants, which are rarely qualified as more than weeds. The third part gives me the most work, but pays back handsomely: the studio and greenhouse. This is where the tender seedlings begin to acclimatize and gain strength to endure the cold early-spring months with hurricane-grade winds.

The gardening year begins when the days with sunshine hours grow longer and the seeds germinate fast. My edible garden starts with seedlings: traditional and unique, heritage and hybrid, and sometimes surprise ones. I also grow plants from flower seeds, which I collect with passion everywhere. I learned how to propagate cuttings, make topiaries, duplicate plants by dividing their roots. These are my new skills learned as a gardener. When I started, I wanted to build a physical relationship with the earth, wanted to feel abundance, to surround myself in the sea of flowers and the unequalled colours that their petals give us. When we found this property on the East Coast of Canada and moved from Ontario 18 years ago, there was much we did not know about it. We continue to learn.

Anna Torma’s garden, Baie Verte, New Brunswick, fall 2019.

Anna Torma’s garden, Baie Verte, New Brunswick, fall 2019.

This is the unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik and Mi’kmaq Peoples, skilled in hunting, fishery and basket-making. Also known to some as Baie Verte, this place was once an Acadian village of only a few families, colonized by French explorers in the late 17th century, among other settlements in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The low coastal tide here allowed farmers to make an effective dyke system and produce sweetgrass pastures and salt-marsh hay. They had cattle-raising and fishing practices. After the Expulsion of the Acadians began in 1755, parts of this place were handed out to English soldiers as granted lands. According to local historian Jean-Luc Chasse, the village was also used as a refugee camp for Acadians after the nearby Fort Beauséjour fell to the British. Those soldiers wanted to reach Prince Edward Island, still a French colony for several more years, and spent the waiting time in Baie Verte while en route. This complicated local history is, inevitably, another foundation of my gardening practice.

The artworks I make in my garden-side studio are textile objects, embroidered by hand. I often use a linen base and silk threads, the best materials to complete fine needlework. Strong narrative elements with darker undertones usually dominate the surface of my pieces: I work with the idea of Dionysian feelings, portraying male and female figures interlaced by real and imagined vegetation, suggesting connectedness in an earthly microcosm. I also want to show the enjoyment and appreciation of myths and legends of different cultures, sexualities, flowers, fruits, colours, and living and imagined creatures, seeing the environment and human identity as a whole but fragile, and always changing, subject.

“I follow in my grandparents’ footsteps when I believe that gardening is meaningful—that it rejuvenates the soul and germinates, again and again, a kind of hope.”

This year’s harvests have also been defined by change. In early spring of 2020, because of pandemic isolation, I had more time to establish my gardening season. I made practical decisions. I enlarged the vegetable paths, made a separate, elevated place for the tomatoes, planted 16 trees and collected seaweeds for next year’s mulching. The impact of the slow pandemic time on the garden has not ended there. I went back to reading and researching about climate, the atmosphere and plant life, and was interested to know more about the relationship between humanity and nature. I learned that in this age of extraction and consumption of hydrocarbons, nature and culture are no longer distinguishable. Our oxygen-rich atmosphere, made by plants, is in danger. Our very existence is in danger. Infinite living beings, our cohabitants, rely on the plants’ metabolic excretion—oxygen—and are in danger as well. Our living conditions, our ability to survive, depend on ecological thinking: the realization that the earth is a closed system, that everything is connected. All our intellectual and artistic attention on a micro- and macrocosmic scale is needed to stop the magnitude of disaster.

Here is something I read this spring, from philosopher Emanuele Coccia’s 2018 text “The Cosmic Garden,” that has stayed with me: “Every garden is the production of an atmosphere. Every garden is a technique that has to make breathing possible.” In winter, my garden diary is a good help. I can look back on my successes and disasters, learn from the facts, then follow my instincts to imagine the next year’s adventures. I follow in my grandparents’ footsteps when I believe that gardening is meaningful—that it rejuvenates the soul and germinates, again and again, a kind of hope.