In her first solo exhibition, “An Exploration of Resilience and Resistance,” Kali Spitzer filled a gallery with Indigenous women, queer, trans and non-binary folks—people I know from back home, from The Rez and from down the block. These are the people I grew up with, people in my communities whose care and love I call home. No, I don’t know them personally. But standing in front of their images, I know them. Because with her exhibition at Grunt Gallery, Spitzer is exhibiting a healing I know well—sibling medicine.

Each photograph in “An Exploration of Resilience and Resistance” has an accompanying audio track, which can be listened to on a headset, meant to allow those photographed to speak in whatever way they chose. Listening to the audio is like sharing a whispered secret. For me, the audio aspect of the images evokes “whisper networks” created among Indigenous women and queer and trans Indigenous peoples to survive misogynist spaces and violence in their communities. Spitzer references networks of care in another intimate element of the show: the scale of the photographs themselves. All are 40 x 30 inches in size, which lends to the intimacy of viewing them. The photographs feel like personal family portraits on the wall in your grandma’s living room. The open space of the gallery and the way the images face one another makes it seem like those photographed are in constant conversation with one another, like I used to imagine the people in my grandma’s photographs would be when everyone was fast asleep late at night.

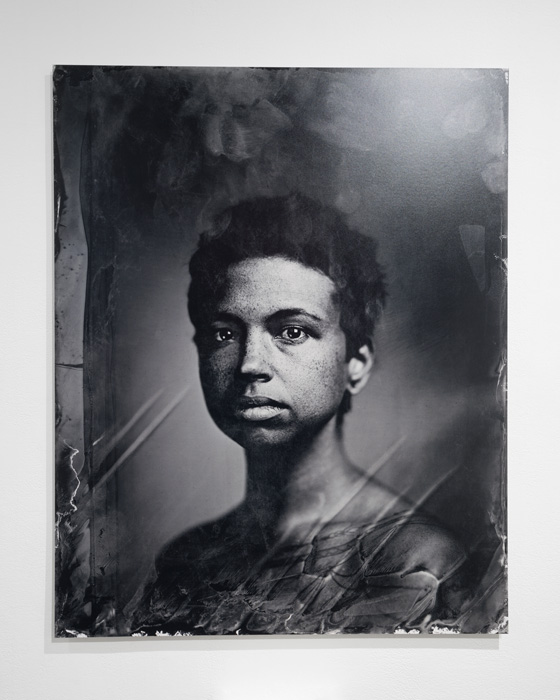

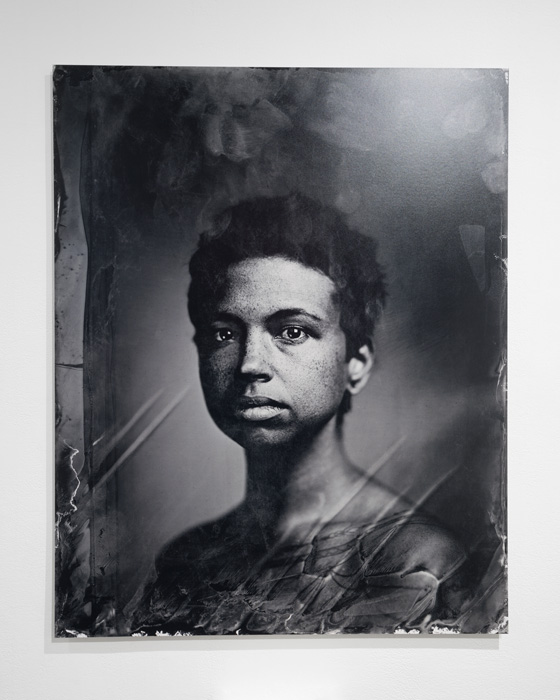

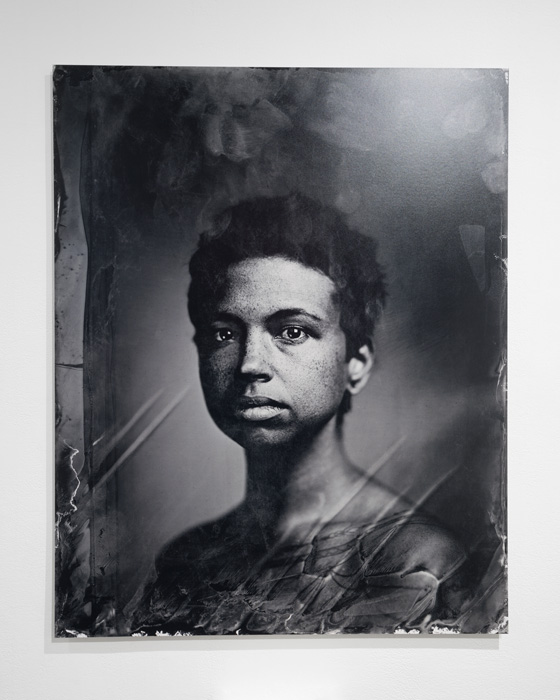

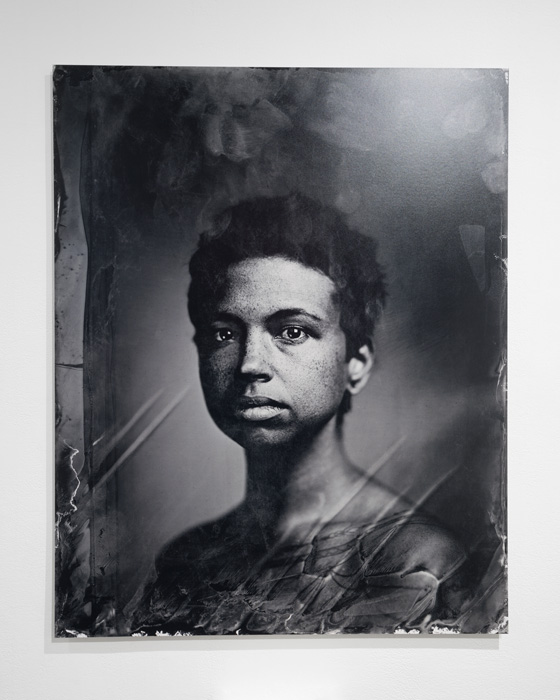

Spitzer’s images are arrestingly beautiful, of course in part due to those photographed. But the tintype method she uses gives them a romantic gothic aesthetic as well. The process darkens the image and its sitter, creating a deep, rich, billowing texture across its surface. Much like the historical photos they reference, Spitzer’s photographs depict dark skin tones, wrinkles, scars and other features. When I used to look at historical photos of Indigenous peoples, I would notice the ancestors’ skin was darker than mine is now. I’ve often wondered, Would my ancestors recognize my face, if I travelled back in time? It wasn’t until learning about Spitzer’s process, and how the tintype method darkens the skin tones it captures, that historical photography began to take on a new meaning for me. Suddenly these images I had studied endlessly since my entrance into Indigenous art history appeared beautiful in their exaggeration instead of a fetishized NDN gothic horror come to life.

Historical photos of Indigenous peoples ultimately served an imperial and colonial project: the use of voyeuristic, orientalist, and fetishistic cultural representation to legitimize imperialism and settler colonialism.

I’ve always thought NDNs are great at horror. We tell stories around campfires that come from the scariest of ancient storylines. We share horrors that stir up such fright they can even mask traumas. We tell scary stories that reveal the beautiful fragility and symbiosis between life and death, much like our ceremonies prepare us for. I think back to the history photos that were taken of my ancestors, portraying what ethnographers thought to be dying peoples. I believed that historical photos of Indigenous peoples were that same horror story Derrida told when he described archive fever—the deadening of Indigenous communities by institutions such as museums, and the voyeuristic fascination of collecting objects from apparently dying communities. Historical photos of Indigenous peoples ultimately served an imperial and colonial project: the use of voyeuristic, orientalist and fetishistic cultural representation to legitimize imperialism and settler colonialism; and an ongoing reference to such photos in an attempt convince us that our ancestors, and that we, no longer exist; that we are something else, something other than Indigenous, and to legitimate access to Indigenous resources and land.

But Spitzer reclaims the tintype method for modern Indigifemmes, not the gazes of old white men and women. By referencing historical photos of Indigenous peoples, Spitzer acknowledges the colonial traumas associated with being photographed as an Indigenous person. Spitzer’s images are not the result of an artist inflicting their will—here individuals collaborated with Spitzer to represent themselves and gain autonomy over their depiction. Spitzer wants to heal shared traumas through the sibling bonds formed during collaborative processes. In this way, part of the artwork is the creation of trust- and protocol-based relationships. Spitzer’s process is one of healing and solace, fostered together as Indigenous peoples. There is an implicit vulnerability here, in the face of an industry, audience and medium that imagines Indigenous peoples as deadened. Spitzer is like Brené Brown for brown and Black girls—our hearts need a little more care than the hearts of white women, living in a world made in their image.

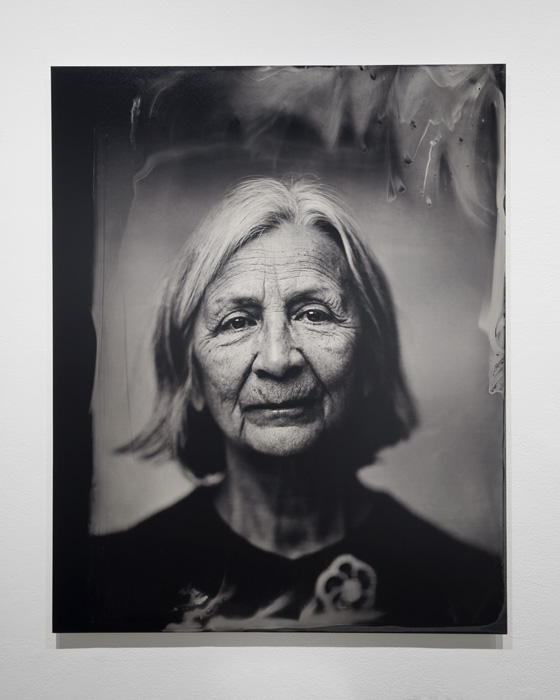

Kali Spitzer, Val Napoleon, 2018. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Kali Spitzer, Val Napoleon, 2018. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

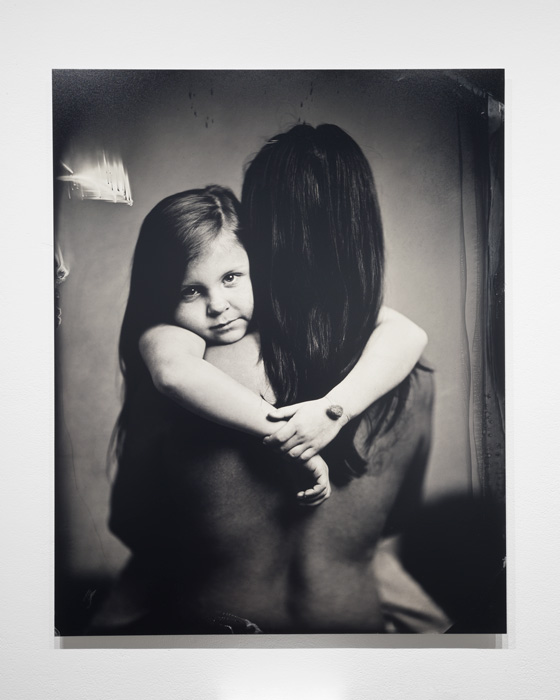

Kali Spitzer, Betsy saw Bisou Bisou saw Betsy, 2018. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Kali Spitzer, Betsy saw Bisou Bisou saw Betsy, 2018. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Mother and child embrace and defiantly return the settler gaze in Vora-Allen Wickliffe and Son Chaske-Waste Kaitaki Twiss (2018). Spitzer is not representing a National Geographic–esque depiction of “primitive” Indigenous mothering. Instead, Spitzer contends that Indigenous mothers are enough without the imposition of a colonial rhetoric of white motherhood imposed on Indigenous homes. Indigenous mothers have their own traditions of community-engaged parenting that existed on Turtle Island long before the settler state and its intrusive arms. In Erena Arapere and Daughter Parekohatu Arapere (2018) mother and child are depicted breastfeeding, what Leanne Simpson calls the first treaty. Indigenous parents have had corporations and institutions impede on their ability to safely breastfeed their children for generations—this is an act of defiance and reclamation. In Betsy saw Bisou, Bisou saw Betsy (2018) parent and child are depicted embracing, a reminder of the intimate bonds of love that residential schools, and now foster care, attempt to eradicate from our communities. This is what is at stake, and why Indigenous communities fight for reproductive and parenting sovereignties. In Spitzer’s catalog of femme histories, there are also proud matriarchs, such as in Val Napoleon (2018), and strong siblings in regalia unabashedly displaying their culture with various forms of NDN bling, such as in the photographs Sister (2016) and Cara Romero (2016). But there are also individuals who refuse Indigenous signifiers, who refuse, as Alicia Elliott has written, to be the noble savage of photography’s past, such as in Kiniaii (2016), and who are fierce Indigiqueens regardless.

Spitzer’s aesthetics reveal the queer disappeared from The Discipline of Indigenous art history, but also the queer Indigenous future defiantly opposed to that erasure.

I know what you must be thinking, dear Indigenous reader—here I am, another NDN talking about the disappearing Indian in art. What a cliché. But Spitzer is portraying a different kind of disappearing NDN, and there’s nuance conveyed that is subtle and worthy of attention. But first I will need to talk about The Discipline of Indigenous art history and its increasingly trending forms of “futurism.” Grace Dillon has asked of the future imaginary, “Does [science fiction] have the capacity to envision Native futures, indigenous hopes, and dreams recovered by rethinking the past in a new framework?” Similarly, The Discipline of Indigenous art and Indigenous studies considers Indigenous futurism as any instance of creative depiction of Indigenous peoples in the future, an assertion tied to identity politics.

Lee Edelman has argued that there is no escape from the present into the future, that for those deemed queer, there is only a violent present repeating itself. The future is a neoliberal fallacy of the status quo—one that, regrettably, like a good queer thinker, I need pray at the alter of psychoanalytical theory to explain. As Billy-Ray Belcourt wrote in his poem “IF I HAVE A BODY, LET IT BE A BOOK OF SAD POEMS,” in his book This Wound is a World, “ok yes, i have been reading a bit of psychoanalysis lately, forgive me. i am desperate. desperate to figure out how someone like me is still here.” Many a “desperate” queer NDN has found themself at the mercy of the psychoanalytic to explain what it feels like to be a living ghost, an impossibility, a body fighting for legibility somewhere in the in-between.

Edelman was interested in the child as a location upon which society projects its future aspirations, particularly with Freud’s theory of childhood development and how it accounts for a world of imaginary relations. Freud argued that we live in a symbolic order, a psychic, physical and material space that manifests through symbolic forms such as language. And Edelman believed that the recognizable forms that construct identity are actually a fantasy made through said symbolic order. Freud’s world of imaginary relations is verbose, convoluted and perhaps elitist, it’s true, but it also helps us contend with the queer in The Discipline.

“Big P” Indigenous Politics that centralize identity formation projects such as self and sovereignties appear radical but are actually formed through processes of othering, through competition between differing forms of identity for recognition within the symbolic order. When we participate in a symbolic order, we are always seeking likeness, and thus difference, simultaneously. Thus, we are grounding Indigenous Politics in an inherent exclusion. The Discipline is a world of imaginary relations where we are all required to have the same signifiers to participate. We compete for recognition within The Discipline through forms of sovereignty and selfhood, and within the larger arena of competing identities under a single neoliberal order (a sovereign people and sovereign nations). But what is a world of imaginary relations for the queer of The Discipline, for all those who possess no future, no sovereignty, no selfhood, and who, under the settler colonial order, are not a part of this people or nation?

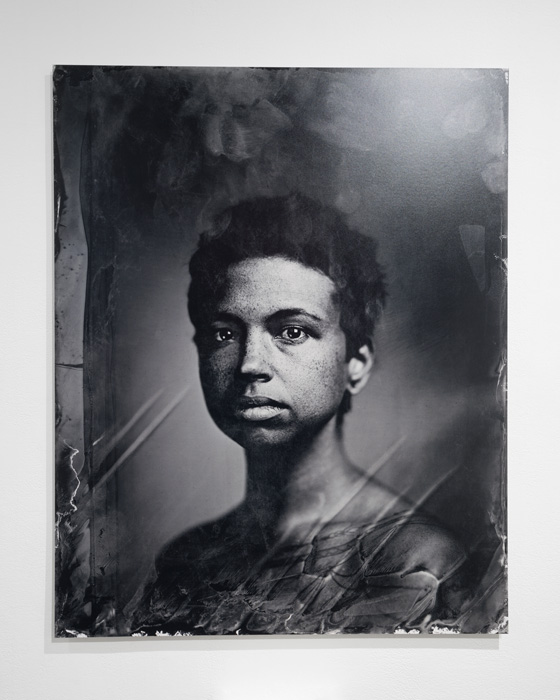

Kali Spitzer, Holland Andrews, 2018. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Kali Spitzer, Meiko Meredith, 2015. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Kali Spitzer, Datura, 2015. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Kali Spitzer, Cora-Allen Wickliffe and Son Chaske-Waste Kaitiaki Twiss, 2018. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Kali Spitzer, Erena Arapere and Daughter Parekohatu Arapere, 2018. Archival C Print of scanned Tintype. 30x40 inches. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

I’m not arguing that queer peoples don’t exist in Indigenous art. Queer, here, is not meant to be just another identity-formation project. I want to consider Kali Spitzer’s photography as an account for queer Indigenous possibility rather than identity. The Discipline imagines queer theory as outside itself. The queer, to The Discipline, signifies whatever refuses intelligibility within its signifiers of sovereign and self. This might be because of The Discipline’s fixation on identity politics and an assumption that the “queer” is just another form of identity formation—identity alternative to, and competing with, Indigenous selfhood and sovereignties. But queer (possibility) is not an identity: it’s an anti-identarian project.

Spitzer’s Meiko Meredith (2015) captures an Indigenous person in physical bondage, as denoted by the harness on their torso—one of those whose bodies and representations were historically deemed too queer for historical and anthropological Indigenous art. The image addresses the tension of being an Indigenous person queer within The Discipline, who possesses no future but has been forced through a symbolic order to fruitlessly grasp at what The Discipline outlines as the Indigenous future. The denial of the queer within The Discipline can be seen through the continued return to historical figures like We’wha to analyze “Two-Spirit” perspectives, and the consistent pushing out of emerging queered voices that actually articulate our beautiful, queer Indigenous present. Even when allowed the space to speak, these perspectives remain niche and alternative to The Discipline.

Spitzer is representing a different kind of disappearing NDN—the queer, disappeared from The Discipline, and using aesthetics to do so. The queer Indigenous future is about more than having survived a genocide and continuing into a neoliberal future. The queer Indigenous future is an ethic and a way of utilizing aesthetic conventions as an anti-colonial way of being and, in doing so, exposing what’s real outside of the symbolic order: The Real. The Real isn’t something that can be explained through language because it evades the symbolic order that encompasses language as a form, and that only perpetuates identity-politic driven community formation. Art provides a potent clearing to grasp at that which we cannot yet know when oppressed under a symbolic order, but that Inidgiqueers and Indigenous trans peoples know exists because we exist and embody it, thereby confounding the symbolic order of The Discipline. The Real is alternative family structures, non-binary gender presentation and futurist Indigenous fashion. Aesthetics hint at The Real, at this something that escapes language, and exposes the symbolic order. No, we can never fully get out of the symbolic order, but Aesthetics like Spitzer’s help us lift its veneer by exposing unconsciousness, what might emerge from beneath the symbolic order, on an intuitive and unadulterated level.

Kali Spitzer, “An Exploration of Resilience and Resistance,” 2019. Installation view. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Kali Spitzer, “An Exploration of Resilience and Resistance,” 2019. Installation view. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Spitzer’s aesthetics reveal the queer disappeared from The Discipline, but also the queer Indigenous future defiantly opposed to that erasure. Every image in “An Exploration of Resilience and Resistance” was breathtaking but I found myself standing in front of Datura (2015) for an extended period of time. Datura bears their chest—a chest made indecipherable because of Datura’s refusal to let the audiences see their face, which they cover with a T-shirt pulled over their head. The audience plays a role here: Does the audience sexualize the image, despite Datura’s adamant refusal? What does it mean if the audience is projecting intent, a sexualized ownership over the image, if the gender of Datura remains ambiguous? Datura confuses gender conventions with their intentional ambiguity, forcing the viewer to confront their own internalized signifiers of normative gender. Like Datura, Holland Andrews (2018) also rejects typical signifiers of Indigenous femininities such as long hair and beaded jewelry. Datura and Holland Andrews expose The Real by refusing to ascribe to gendered signifiers that come to define the roles of good Indigenous women. Datura and Holland expose a world outside of the symbolic order. Again, we witness a whisper that blurs and uncomfortably exposes The Discipline’s identity prerogatives of self and sovereignty, because the audience knows that these are also images of “resistance” and “resilience.”

Emily Riddle argues that, in their actions every day, queer and trans Indigenous peoples enact a different kind of governance, one seldom talked about but which represents a powerful political force. Just as queer and trans Indigenous peoples enact a different kind of governance, I argue that the queer enacts a different kind of futurism. A queer Indigenous project holds that we need to transform relationalities before we can move past any form of identity or symbolic order. What if we embraced nuance, difference and deviance as an anti-colonial ontology, embracing shared separation, exposing the void and admitting things are already unmade. Could this be a relational turn—no grandeur project or mission, just an intention to be together in our separation, in a way that isn’t part of a neoliberal design? The queer Indigenous future emerges from this relational offering: not simply as any aesthetic depiction of Indigenous peoples in the futures—a formation of Indigenous futurism based on identity politics and participation in the symbolic order—but as an ethical protocol, a way of relating and a vision of possible and otherwise worlds.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Bobby Benedicto for giving me feedback and edits on early drafts of this review.

Kali Spitzer, “An Exploration of Resilience and Resistance,” 2019. Installation view. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Kali Spitzer, “An Exploration of Resilience and Resistance,” 2019. Installation view. Courtesy/grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.