When issues around art collections and cultural property emerge, lawyers are often the people who deal most intimately with the resulting conflicts and resolutions.

“I would say that art feels like magic to a lot of people,” Toronto lawyer Jonathan Sommer reflects. “And that’s the beauty of it. But you can’t let the magical qualities of art lead to magical thinking in the way you buy it. Especially if it’s meant for investment purposes, or partly for investment purposes.” In his experience, not many artworks increase in value over time.

One key, Sommer says, is to stay rational and get things like provenance and other promises about the work in writing because forgeries and bad- faith dealers are more prolific than one might expect.

François Le Moine is a Montreal lawyer who specializes in art, cultural heritage and copyright legislation. He also teaches on these matters at Université de Montréal. In his experience, art theft is much more widespread in Canada than most collectors are aware. “We are talking hundreds of thefts every year,” says Le Moine, “and the recovery rate is only 10 to 15 per cent.”

Le Moine advises that collectors thoroughly document their artworks to increase the chances that a work will be recovered if stolen. “It’s quite important to have copies of the artworks available,” and not just on a personal hard drive. “All of the acquisition documentation and high-resolution pictures—of both the front and reverse sides of an artwork—will really help when you are trying to fight for your art later on,” especially if it surfaces on the secondary market or elsewhere.

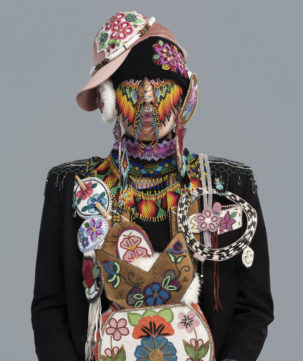

Sarah Beamish, a Toronto lawyer of Ngaruahinerangi (Maori) and Western European ancestry, notes that collectors of cultural property should research which communities might have ownership over Indigenous works before purchasing them. “The farther back you are going [in terms of the age of the artwork] the better idea it is to be looking into those things,” Beamish notes.

In the future, Indigenous law could become part of cultural property management in Canada too. “When we talk about laws, we usually think federal or provincial,” says Beamish. “But as we take things like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples more seriously, it’s worth considering: What about Indigenous people’s laws?” She notes that colonial law focuses on individual ownership, where Indigenous laws focus more on collective ownership.

Denis Walz is a Vancouver lawyer and art collector. In his legal work, he thinks through the long-term timelines of an art practice. Under copyright law, Walz notes, the collector does not have moral rights or copyright to the artwork, only certain property rights, and is thus more of a steward than anything else.

“You have to care for the artwork, you are custodian of this work, whatever it is, and it should outlast you,” Walz says. “You have a duty to store and handle things appropriately so they are not damaged by light or other elements.”

This post is adapted from the Canadian Art Collecting Guide, out in our Spring 2020 issue, “Influence.”