Men never send dick pics, only sunsets. The view from my balcony, they say. Texted gold-and-black horizons, Tinder photos of built glitter against mountains. A sunset is harder than a dick. Because what do you even say to that? Meteorologists say it’s the particles that make the scarlet: smoke from a burning forest, gaseous volcanic sulphur, engine soot, industrial gas. Light scatters: violet the most, red the least. Our earth-wrecking makes the sky so good and ’grammable. But that’s not how you respond to a man’s sunset. You’re supposed to say beautiful, I’d love to see it sometime. The people of Instagram are making trips to photograph things before they’re gone or before we’re all dead, whichever comes first. We have to see the glacier because we’re melting it. We have to see the eclipse before smog obscures the sun forever. I took a plane from Ohio to Tennessee and back in one day just to see the same sun and moon we have here at home. I would have driven out of my city to a place way beyond the light pollution to see the meteor shower last week, but I was afraid of that kind of dark—outdoors dark, preferred by serial killers—so instead I looked at astrology internet on my phone and tried to figure out whether I’ll die alone.

The apocalypse will happen during my lifetime, if I can figure out how to live long enough. I want to be a hundred in a good-looking flesh case. I’ve been smearing my skin with the secretions of snails, 24-karat-gold flecks suspended in serum, iron dust from the Toluca meteorite. I dress my hair like Jezebel’s as she waited at her window for Jehu. It has the lustre of oil that travelled seven thousand miles. This won’t end well. I know men: they hunted the sea mink for its pelt, laying traps, sniffing minks out with dogs, digging out mink homes with shovels and crowbars, smoking minks out of holes. Before they went extinct, the sea minks turned nocturnal, doing what they could in secret night, closing their curtains and extinguishing their lamps and not texting the men back.

The weather here is so mean it seems like someone might be mad at me: half-boiling slicks of summer, deep freezes, blizzards, floods, tornadoes, all shifting so fast that the air feels unsettled, like it might snap if I say the wrong thing. Inside the city, downpours weep into our basements; outside the city, trees grow like panic attacks. GOD LOVES YOU said a sign in the countryside the last time I drove a hundred miles out. SOMEHOW, NOTHING SATISFIES LIKE BEEF! said another. Nothing? That’s right: some things make a man hungrier. Some pelts are gateway pelts. Some eclipses are neat, but the eclipse-chasers will tell you that if you really want to see a good one— no clouds, no light pollution, totality—you need to fly halfway around the world. When I got to where I was going out in the country, the ground was covered in snow. In mid-April! A couple days after it hit 70! Climate change, we all said, and I realized I’ve never really thought about that, couldn’t tell you exactly what it means, having read maybe two articles about climate change and three thousand about the astrology of romantic compatibility, because I’m going to die long before we end the world. In a bed, probably. By a man. They’ve shown me they can end me with their breath-stopping hands and flicking knives. But I’ve been thinking lately, maybe I do want to die with my friends in the mass extinction that follows the full melt. I’ll be a good survivor: my body can learn to do anything.

Once, a man asked me up to see his view. I lived across the street, so mine was nearly the same. But I did go up. We sat on the balcony and he said, Now I’m going to tell you all the things I’m going to do to you. He was right. His view was so much different from mine. His apartment was higher up than the window Jehu had Jezebel thrown from before horse-stomping her corpse into spreadable pulp. This man was the only person on Earth who knew my whereabouts. The sun had already set, so I just had to take his word for it when he told me the sunsets were so good, unbelievable, but he didn’t say to die for, because that’s not the kind of thing a man like that says out loud.

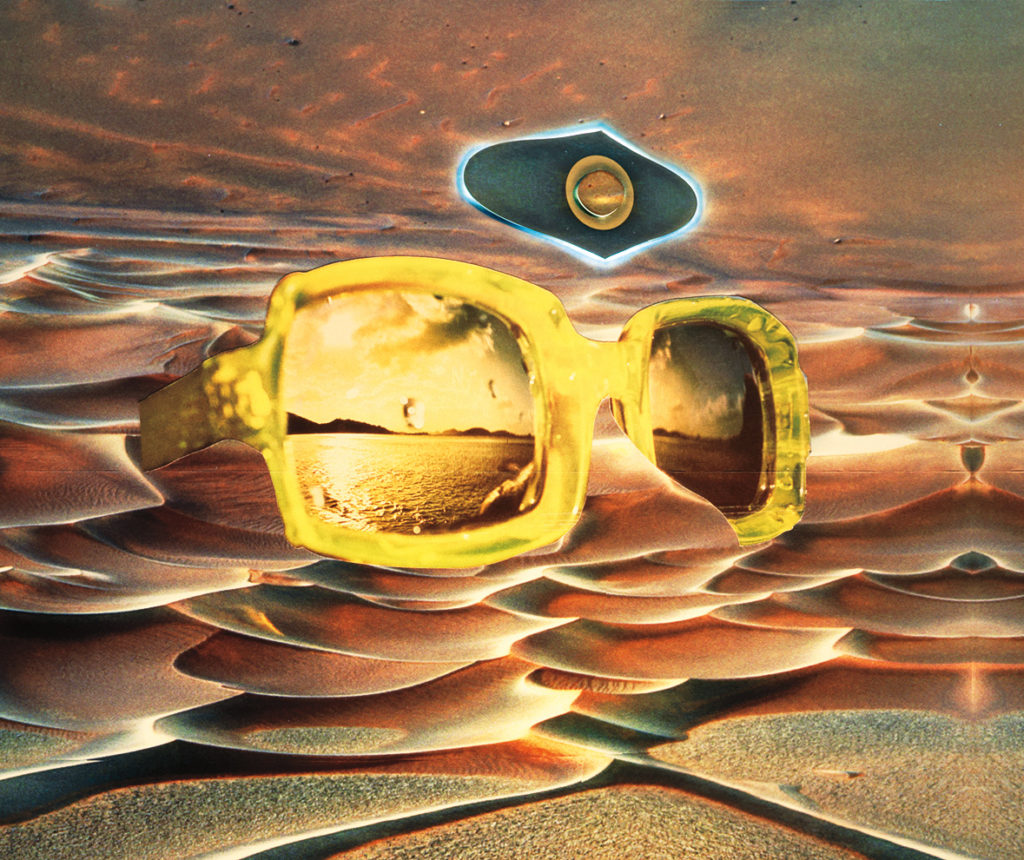

Elizabeth Zvonar, The Experience (detail), 2015. Collage image printed on vinyl with offset backlit third eye, 6.09 x 16.4 m. Courtesy the artist/Daniel Faria Gallery.

Elizabeth Zvonar, The Experience (detail), 2015. Collage image printed on vinyl with offset backlit third eye, 6.09 x 16.4 m. Courtesy the artist/Daniel Faria Gallery.