In reading HIV/AIDS through the lens of Canadian art, we are often taught to think within the confines of a historical canon that encompasses the work of a few select artists. Undoubtedly, the contributions of household names such as General Idea, AA Bronson, John Greyson and Stephen Andrews continue to inspire important dialogue on this subject.

But today, the emergence of a younger, perhaps less visible, group of artists demands that we expand the conversation. As opposed to practices that took shape directly within the early years of the AIDS crisis, these artists address a different set of concerns that reflect their youth and shared place in history.

Rejecting both the nostalgia of a pre-AIDS historical moment and exclusionary, linear narratives of LGBT progress, five artists in particular come to mind. Together, they help reveal the complex socio-political situation we find ourselves in today.

Notably, these artists stand against the backdrop of current discussions on the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure, sex in the time of PrEP, access to affordable treatment and the impact of HIV/AIDS on at-risk and marginalized communities. Their work contributes to this discourse through considerations of the ever-present medical realities of HIV, the pervasiveness of the signifier “AIDS” as a force of stigmatization and violence, and the effects of traumatic memory on identity and community.

What remains consistent in each of the practices outlined here is an interest in “HIV/AIDS” as an impossible object of representation. Channeling this impossibility, these artists honour their youth and shared place in history by teaching us that, when faced with this subject, our critical attention cannot simply be restricted to those who “have” HIV. Instead, these artists demonstrate the ways in which the politics of the virus continue to be implicated by each of us in aspects of everyday life. In doing so, they reveal how we are a society with “AIDS,” and that we have never been “post-AIDS.”

Given the recent appearance of several major North American exhibitions focusing on the relationship between art and HIV/AIDS—such as “Art AIDS America” at the Tacoma Art Museum, “One day this kid will get larger” at the DePaul Art Museum, “General Idea: Broken Time” at Museo Jumex and “Focus: Perfection — Robert Mapplethorpe” at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal—now seems to be an ideal time to revisit this subject through the work of some of Canada’s most ambitious and unruly young artists.

Yet: No matter how diverse this group of artists may appear to be, one must be attentive to the fact that an exhaustive, all-encompassing portrait of art and HIV/AIDS in Canada cannot be created. Indeed, the very making of this list of names raises key questions on access and visibility: Which individuals in our society are granted the time and resources to maintain an art practice? And which of these individuals are able to openly communicate about HIV status in their work? Who fails to enter into the conversation in the first place?

Vincent Chevalier, Á Vancouver, 2016. Video.

Vincent Chevalier, Á Vancouver, 2016. Video.

Vincent Chevalier

Vincent Chevalier addresses the limits of self-knowledge within a conceptual framework that is at once camp and melancholic. Operating within the realm of the semi-autobiographical, his works cultivate a persona that is simultaneously fictional and authentic, scripted and confessing, determined by history and resistant to essentialist readings of identity politics.

This dynamic is evident in his striking video So… when did you figure out that you had AIDS? (2010), which features the artist, at the age of 13, playing the role of a “man dying from AIDS” on a pretend daytime talk show. Operating in a tense space between solemnity and levity, this uncomfortably lighthearted childhood portrayal precedes the artist’s HIV-positive diagnosis by several years.

À Vancouver (2016), a video essay produced nearly six years later, also centres on the artist’s interest in revisiting his youth. This work offers a portrait of Vancouver that is articulated through distinct, yet parallel, sexual experiences recounted by the artist and his father. The revealing interchange between the two presents a view of Chevalier’s earlier years that shifts between different characters, perspectives, settings and languages.

Both of these works, indicative of Chevalier’s practice in general, demonstrate his commitment to exploring traumatic memory through experimentations with narrative form.

Shayo Detchema, L’Hiver inconsolable, 2014. Animation. 3 minutes 40 seconds.

Shayo Detchema, L’Hiver inconsolable, 2014. Animation. 3 minutes 40 seconds.

Shayo Detchema

What is known and knowable about this thing we call “HIV/AIDS” is first and foremost a matter of storytelling. Shayo Detchema is a video, performance and installation artist who explores this idea by using her body as a tool to construct complex narrative structures in scenes of withdrawal, longing and detachment.

Following this trajectory, Detchema’s video and performance project Chevet (2011) is divided up into the narrative fragments “Jour 1,” “Jour 53” and “Jour 164,” each of which presents rather ambiguous edited scenes of the artist engaging in escapist fantasies and alternative rituals of healing.

Alternatively, one of the artist’s more recent video works, L’Hiver inconsolable (2014), consists of an animated video where multiple versions of two separate self-referential characters perform a rigid choreography, a kind of 2-D digital dance, against a stark white backdrop that signifies a perpetual winter. In these slippery, oftentimes ungraspable self-portraits, Detchema “poeticizes illness” by reframing scenes of everyday life through a DIY surrealist lens.

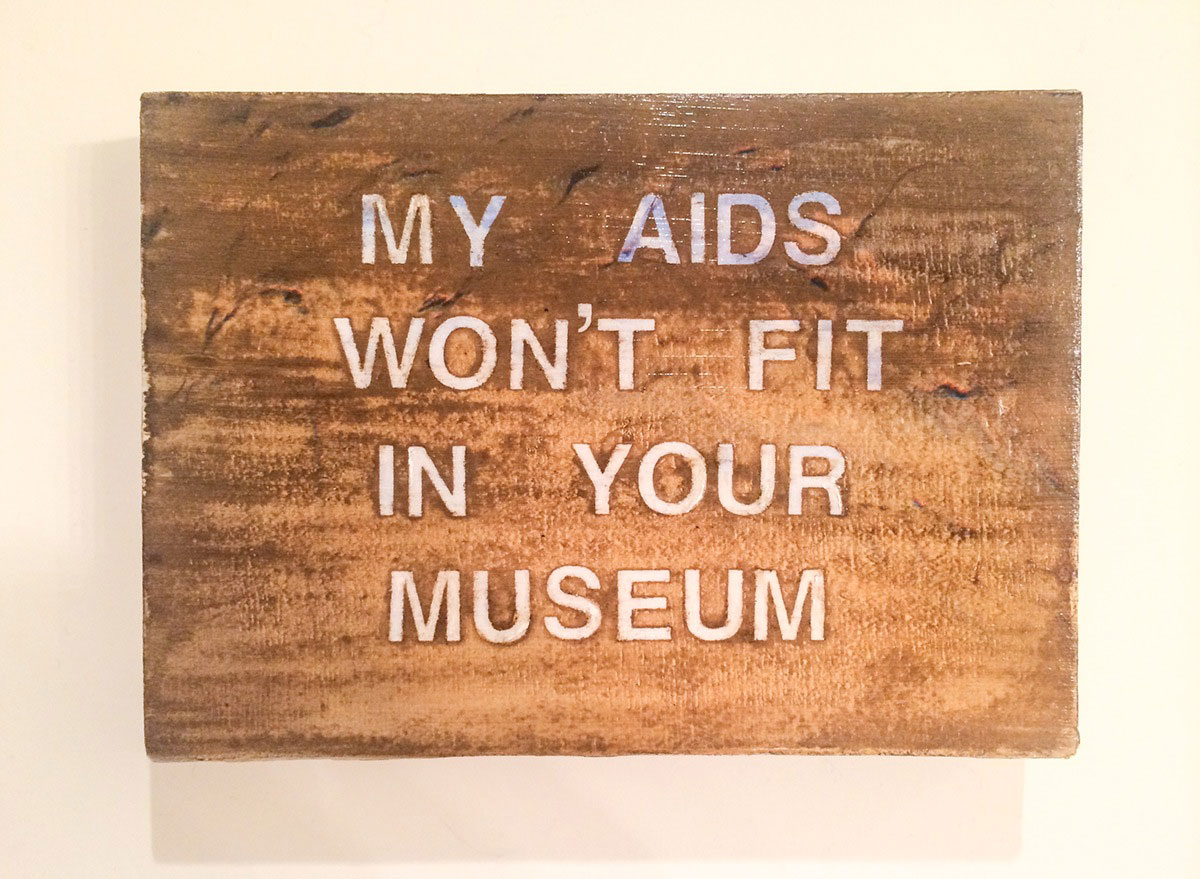

Shan Kelley, With Curators Like These Who Needs a Cure, 2015. Wood block, semen, pubic hair.

Shan Kelley, With Curators Like These Who Needs a Cure, 2015. Wood block, semen, pubic hair.

Shan Kelley

Mixed-media artist Shan Kelley questions the boundaries of public/private life and the politics of bodily non-disclosure by queering processes of signification. Kelley also works to underline the discontents of the term “AIDS art” by pointing to the complexities and contradictions of everyday life that cannot be reduced to the discourse of Western art history.

This interest is expressed in With Curators Like These Who Needs a Cure (2015), a small wood block topped with a varnish of the artist’s semen, an application of pubic hair and bolded text that reads, “MY AIDS WON’T FIT IN YOUR MUSEUM.”

Kelley’s solo exhibition “Clean, Fit, and Decease Free” at Latitude 53 questioned “the feeling of exposure, of oppressive surveillance sexuality, and private life become seemingly-fair game for moral scrutiny and study.” The exhibition featured a diverse selection of works that ranged from Order (Of Canada) (2015), a sideways-hanging Canadian flag covered in dried semen from friends of the artist living with HIV, to Close Enough. A Pictorial Survey of Wikipedia’s Geography of Index Cases (2015), a photo suite presenting stark images of suspected originating sites of disease outbreaks from around the world.

As evident in this exhibition, and in other works, Kelley rejects traditional representations of HIV/AIDS advocacy through his playful use of a conceptual and minimalist visual language.

A work by Jessica Whitbread.

A work by Jessica Whitbread.

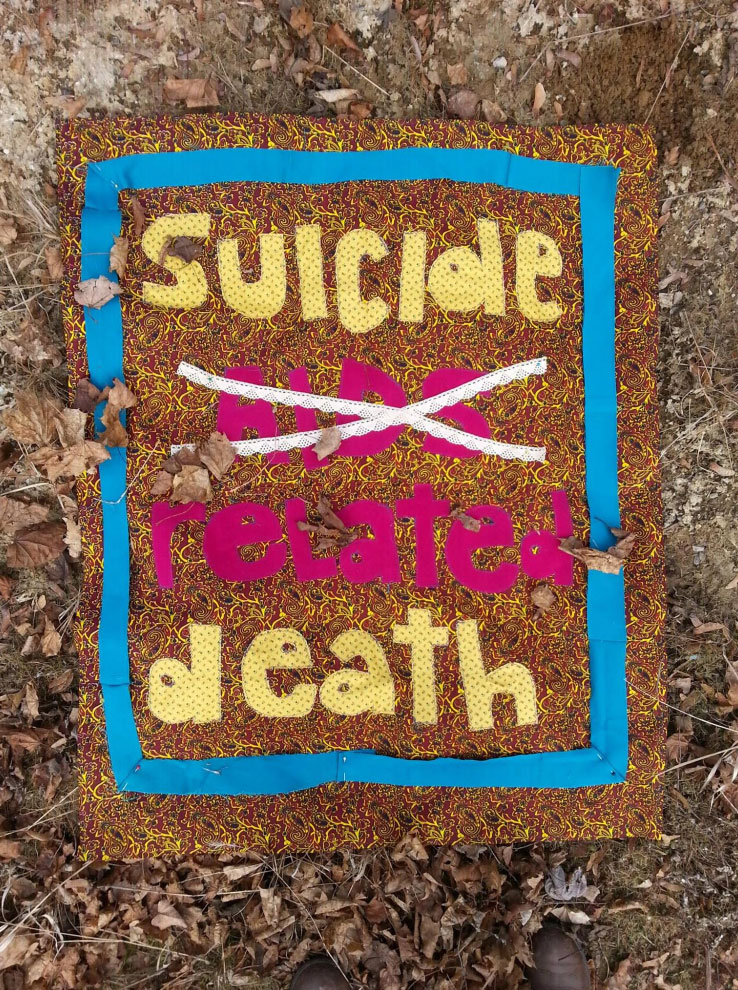

Jessica Whitbread

Jessica Whitbread’s collaborative, socially engaged practice blurs the line between community activism and materialist inquiry. This commitment is perhaps best exemplified by Love Positive Women (2013–), an ongoing correspondence project that provides “a platform for individuals and communities to engage in public and private acts of love and caring for women living with HIV.”

Beginning in 2011 alongside writer and researcher Alexander McClelland, Whitbread also developed PosterVirus. This community based intervention project invites selected artists to create original poster works that are eventually wheat-pasted in the streets and shared online. By promoting representations of autonomy, self-determination and collective resistance, PosterVirus establishes an organized artistic response to the normalization of HIV stigmatization in mainstream culture.

Whitbread’s practice is rooted in a democratic process of exchange that cannot be easily contained within the sterile walls of the white-cube gallery. Moreover, in contrast to the work of certain cultural producers that continue to frame the wide-reaching subject of HIV/AIDS solely through the lens of male homosexual desire, Whitbread challenges us to rethink what this sort of political imagery is supposed to look like and whom it is supposed to represent.

Mikiki, NSA, 2016. Performance at 7a*11d in Toronto.

Mikiki, NSA, 2016. Performance at 7a*11d in Toronto.

Mikiki

Mikiki explores themes of resistance and the reclamation of agency through performance and video works that map out a space between ritual and the absurd. In their highly experimental and rebellious practice, the body is framed as a vehicle to disrupt forms and forces of stigmatization and alienation in contemporary society. In many works, their body is also used to target public-health discourses centred on problematic assumptions about HIV exposure and transmission.

Mikiki provides thoughtful and provocative commentary on these issues in works such as On The Department Of Experiential Medicine (2005–11), in which the artist excavates various fluids from his anus into drinking glasses and toasts to the audience, or Down In A Blaze of Gloryhole (2013), in which the artist interacts with visitors through a DIY glory-hole cabinet.

As with each of the other artists included in this list, it is crucial to emphasize Mikiki’s opposition to certain pressures and expectations put onto artists living with HIV to create work that reflects truths about identity and health status. This tension is well illustrated by a recent performance piece that premiered at 7a*11d titled NSA (2016), where traditional forms of political action based on “radical change” are called into question through a personal exploration of the practice of fucking up and the ethics of self-ownership.

Adam Barbu is a writer and curator living between Toronto and Ottawa. In 2015, he was the recipient of the Middlebrook Prize for Young Canadian Curators. He would like to extend special thanks to Ted Kerr, Alexander McClelland and the team at Visual AIDS for their guidance and feedback on this article.

Shayo Detchema, L'Hiver inconsolable (video still), 2014. Animation. 3 minutes 40 seconds.

Shayo Detchema, L'Hiver inconsolable (video still), 2014. Animation. 3 minutes 40 seconds.