It’s a sight that’s hard to believe: A delicate, pale-green kitchen chair, sitting on a rock in the middle of a rough-watered ocean cove. Waves break over the chair, foam churning through its narrow spindles. Tides rise around it, submerging its legs, then its seat, then its top rail—and then the chair, delicate and almost seafoam coloured itself, emerges as tides recede again.

It’s a sight that’s hard to believe, yes, but the sight is real—as curious crowds along the coast of Maberly, Newfoundland (population: 20) are discovering. It’s an installation by St. John’s artist Will Gill, and it’s one of the standout works of the newly hatched Bonavista Biennale.

Facing out to sea, across the Atlantic, just as so many Newfoundlanders have looked out over centuries to watch for weather, for whales, for fish, for family and friends to come home, this small chair powerfully suggests the intimate, the frail and the human lost to (and persisting despite) the water, the ocean and the abyss.

Gill’s work is also an excellent example of the power of putting art in rural environments—a huge message of world’s newest biennial. Also on offer: meditations on North America’s colonization, situated in the zone where much of this colonization began; takes on what it means to be a visual minority in Newfoundland and Labrador; reworkings of raw spaces left behind by the collapse of the cod fishery; notes on the power of place, and artmaking based in place; and speculations that cultural industries might be able to fill in some of the region’s persistent economic gaps.

“Outdoor presentations [of art] have been going on forever in cities—but not necessarily in rural areas,” says Patricia Grattan, co-curator of the Bonavista Biennale. And Grattan knows of what she speaks; for more than 25 years, she was the head of Newfoundland and Labrador’s biggest art gallery, generating exhibitions that travelled to cities throughout the province. She calls the Bonavista Biennale “a unique conjunction of art, people and place.”

And of the biennial’s process—Gill’s seafaring chair-installation foray included—Grattan adds, “It’s always an adventure.”

Viewing the Bonavista Biennale is an adventure, too: In all, the biennial features an assortment of 23 projects by 26 artists scattered along a 50 kilometre loop of the rugged Bonavista Peninsula. (One of the dangers on this art circuit: errant moose that are rumoured to have a tendency to run into car headlights.)

Thankfully, Grattan’s efforts—and those of her co-curator Catherine Beaudette, a Toronto creative who hosted a “wine-fuelled dinner” some years ago in the small town of Duntara, where she summers, that led to the biennial—yield several worthwhile results. And those results are all on view from now until September 17, just a few hours’ drive from the provincial capital of St. John’s.

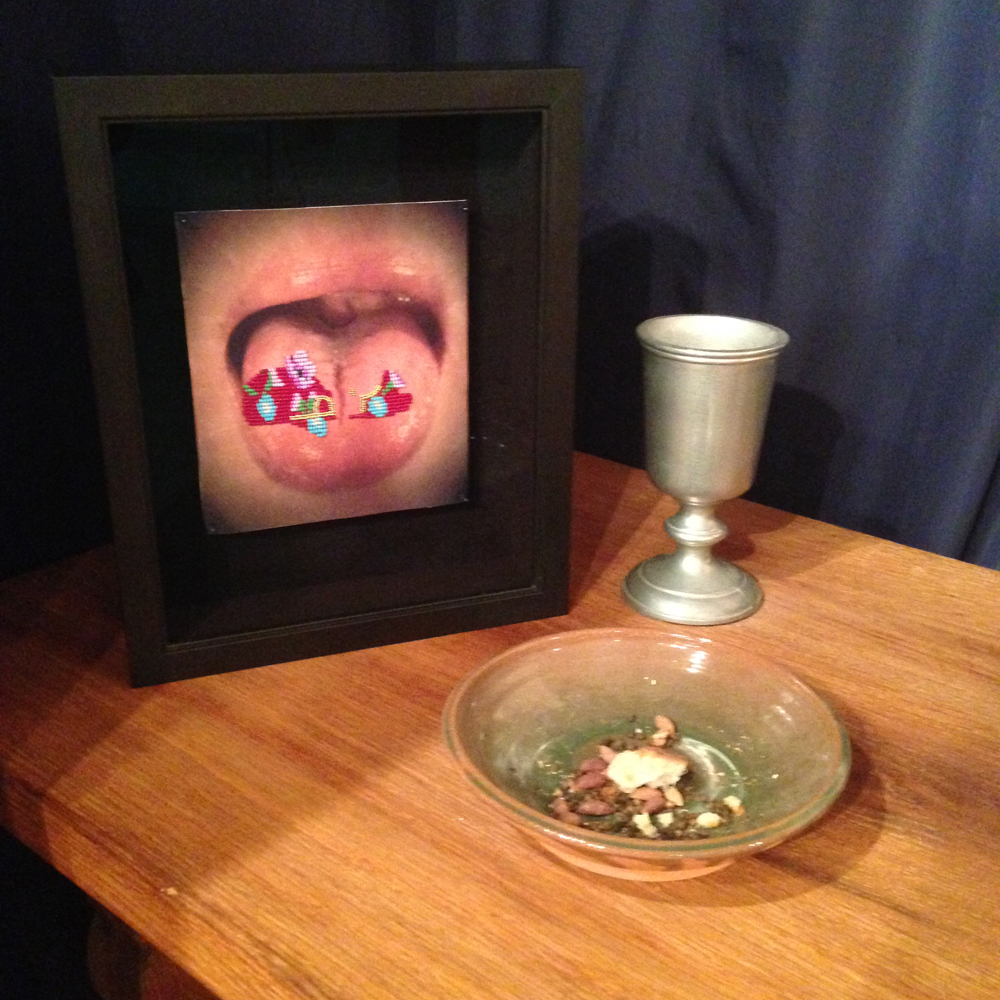

One of Catherine Blackburn’s beaded tongue images offers a counternarrative to the historical display at the Ye Matthew Legacy interpretation centre in Bonavista. Photo: Leah Sandals.

One of Catherine Blackburn’s beaded tongue images offers a counternarrative to the historical display at the Ye Matthew Legacy interpretation centre in Bonavista. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Catherine Blackburn’s interventions at the Ye Matthew Legacy Interpretation Centre in the town of Bonavista, for instance, are another Biennale highlight.

For this work, Blackburn—a young Dene/European artist and jeweller from Saskatchewan—responds to the history of Bonavista as the first landing point of John Cabot in 1497. She also responds to the Ye Matthew as a place that promotes a narrative of Cabot’s “discovery,” rather than a narrative that begins with Cabot, continues with the complete eradication of the Beothuk—the Indigenous people of the island of Newfoundland—in 1829, and continues in other present-day effects of colonization.

“It was through beadwork that I found my way back to cultural investigation,” Blackburn says of her own journey as an artist from Western-style painting to beadwork and quillwork. “What I love about beadwork is I can address culture and history just by using beads.”

For her work in Bonavista, Blackburn beaded traditional floral motifs, as well as First Nations syllabics, over images of tongues—so that the work summons trauma both physical and cultural. Then she placed these images within the Ye Matthew museum space.

“One of my mother’s greatest regrets was not teaching us the Dene language,” Blackburn says. Perhaps this is not surprising, though, given that “one way children were reprimanded for speaking their language [in residential schools] was to put pins through their tongues.”

Blackburn’s use of stitchery on the images of tongues viscerally evokes the punishment First Nations children experienced, while also expressing some of the reclaiming of Indigenous legacies since. Another, related series of beaded tea bags also points to colonialism and consumption, travel and taste.

“Those traditional techniques were banned, but now there is a reclaiming of sovereignty over the body,” Blackburn says. “I’m speaking to resistance, survivance and revival.”

Some of Omar Badrin’s crocheted works at the Sealer’s Interpretation Centre in Elliston. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Some of Omar Badrin’s crocheted works at the Sealer’s Interpretation Centre in Elliston. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Reviving traditional craft in a different way is Omar Badrin’s installation at Sealer’s Interpretation Centre in Elliston (a town which advertises itself on welcome signs as “Root Cellar Capital of the World!”).

Born in Malaysia, raised in Newfoundland and now based in Toronto, Badrin uses the traditional Newfoundland materials of fishing line—as well as Newfoundland traditions of crochet, crucial to fishing-net creation and repair—to create works that speak to feelings of displacement and permanence, celebration and isolation.

“I identify as a Newfoundlander. Newfoundland is the province where I was raised, and I’m quite familiar with the landscape…. The province heavily influences my studio practice, from the use of materials to the medium of crochet I employ today,” Badrin said in an Akimbo post earlier this year. “Growing up as a visual minority there made Newfoundland a source both of torment and joy. I think these feelings will always be with me. Even though I’ve been living away for over a decade, I still call it home.”

Situating Badrin’s crocheted masks and figures in a gallery dedicated to remembering sealers lost in the 1914 SS Newfoundland tragedy, which claimed 78 working-class Newfoundlander lives, enhances a sense of ghostliness or split consciousness in the work.

On the walls, the interpretation centre has installed large realist paintings by artist John McDonald—whose great-grandfather James Donovan was on the SS Newfoundland and survived in part thanks to a knitted cap taken from his brother after he perished on the ice—document the trauma of that historic event.

Hanging from the ceiling and some of the bare spots on the walls, Badrin’s brightly coloured crocheted masks and columns, some of which have mouths bearing small silver teeth, conjure death and survival in a more expressionistic way.

Works by Dil Hildebrand hang in the under-renovation Wellness Centre in the town of Bonavista. Photo: Brian Ricks.

Works by Dil Hildebrand hang in the under-renovation Wellness Centre in the town of Bonavista. Photo: Brian Ricks.

But it’s not just artworks that stand out at the Bonavista Biennale. A large amount of effort has gone into revitalizing or repurposing disused or raw spaces around the peninsula for art installations.

For instance, one venue is a 1950s-built high school in Bonavista that is currently being renovated into a “wellness centre.” There, amid bare struts and studs, hang works by Montreal artist Dil Hildebrand that speak to fragmentation and repetition. Issues of structure and architecture are also taken up there in minimal photographs by St. John’s artist Ned Pratt.

Riffs on a lack of architectural sustainability, perhaps, show up in a vision of tourist “dream houses” literally falling into the sea, courtesy of Newfoundland artist Matthew Hollett’s films, also installed at the centre.

And Toronto artist Michael Snow rounds out that installation with his video Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids)—a piece that focuses on a windblown curtain in the Newfoundland cabin where he usually summers, the curtain only occasionally revealing views of vistas beyond, and, in context, summoning questions around the extent to which this province’s future can be designed or “seen.”

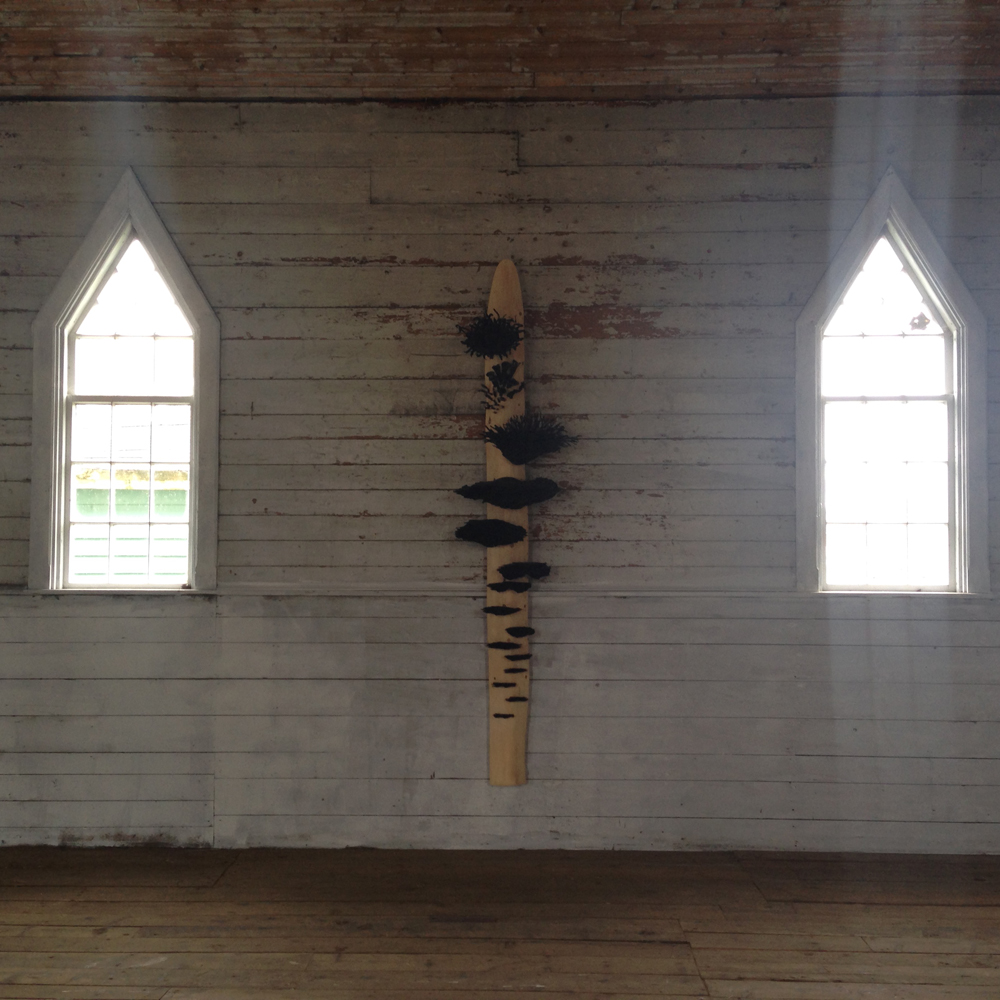

Barbara Daniell’s work, inspired by natural forms of fungi, trees and other Gros Morne biota, is installed in an old one-room schoolhouse. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Barbara Daniell’s work, inspired by natural forms of fungi, trees and other Gros Morne biota, is installed in an old one-room schoolhouse. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Another evocative site on the Bonavista Biennale roster is the Swyers Hill School, currently housing an installation by Woody Point–based artist Barbara Daniell. Constructed in 1880 as a one-room Church of England school, the structure’s peaked windows evoke a pious, sacred quality.

Meanwhile, Daniell’s sculptural installations made of various media evoke the sacredness and wonder of the natural world: blackened fungi, smooth birchbark and intricate nests. Inspired by the landscape around her home near Gros Morne, these works are well matched to contrast and compliment the school’s old Anglican architecture.

Other sites for the Bonavista Biennale have a considerably less lofty (or at least less churchy) history.

The Catalina Salt Fish Plant, located across the road from a grocery store and lumber yard, has a varied legacy. First, it operated for decades as a salt fish plant, and more recently a seal tannery. Beaudette gained access to the space by talking to the local family that used to own it—a process that took some months. Then came the installation.

“When we were installing, we were like, ‘Oh my god, the roof is leaking,’” says Beaudette. Prior to that, before a deep clean, she and her team were confronted with “seal bodily fluids on floor, and piles of blue herring buckets.”

Now, for the biennial, the Catalina Salt Fish Plant plays host to three video installations, all of which speak to environmental change.

One, by Alberta artist Peter von Tiesenhausen, shows a figure wandering among and iceberg bits along an ocean shoreline. Occasionally, he stops to carve the ice with an axe. (Though the piece was filmed in Iceland, it fits in well with the Newfoundland setting.)

Peter von Tiesenhausen’s video installation for the Bonavista Biennale, installed in an old salt-fish plant, pictures coastal environments, water and ice. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Peter von Tiesenhausen’s video installation for the Bonavista Biennale, installed in an old salt-fish plant, pictures coastal environments, water and ice. Photo: Leah Sandals.

The second video installation, by UK-based Canadian artist Kelly Richardson, shows another kind of shoreline—a warm-weather, swampy one based on Caddo Lake in Texas, which was home to the world’s first over-water oil platform in 1911. In this biennial context, it evokes both the Newfoundland economy’s renewed dependence on offshore oil and the changes carbon-driven climate change may bring to the province.

The third video installation at the plant is by Newfoundland artist Marlene Creates. In this video, paired with related photographs, Creates offers a visual dictionary of ice structures and forms as suggested by old vocabularies of the province. The prospect of melting, here, suggests a double disappearance—one of culture and one of nature.

“I found there were 80 terms for different conditions of ice and snow in the Newfoundland vernacular,” Creates says. “I love the sound of these local words”—like “balliscattered,” “devil’s blanket” and “sish”—“in the air, and their relation to the local terrain. Knowing the terms helps me see different phenomena.”

Creates, for her part, views her practice as “tuning and being tuned by a patch of boreal forest.” For the last number of years, Creates has based all of her work—photos, poetry and performance—out of a “six-acre patch of boreal forest” in Portugal Cove that is both her home and her studio.

“Underlying all my work has been an interest in place—not just as a geographic location but as a process,” Creates concludes.

Reinhard Reitzenstein’s installation for the Bonavista Biennale at Knight’s Cove is comprised of nine upside-down, ochre-stained trees along the water and ATV trail. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Reinhard Reitzenstein’s installation for the Bonavista Biennale at Knight’s Cove is comprised of nine upside-down, ochre-stained trees along the water and ATV trail. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Many of the installations at the Bonavista Biennale do seem to say something special about this place and its residents.

Toronto-based artist Reinhard Reitzenstein, for instance, has already received a lot of commentary about his installation of nine upside-down, red ochre– and linseed oil–stained trees along the waterside in Knight’s Cove.

“This is a piece I care deeply about because I care deeply about this place,” says Reitzenstein, who worked with locals to maintain a local ATV trail along the berm next to the installation. Children bike alongside it, too. And a local woodlot owner was instrumental in helping Reitzenstein find the right trees for the project.

Reitzenstein summers in Newfoundland. Though he started doing these types of tree installations back in 1987, he says there are specific resonances here to this place.

“There are allusions here to British and Portuguese navies cutting down [Newfoundland] forests to build their boats,” Reitzenstein says of this installation. He also notes that red ochre and linseed oil were used to preserve fish stages in Newfoundland, as well.

Looking at the work of Doug Guildford—an artist originally from Nova Scotia who has leveraged the Atlantic region’s rich traditions of crocheting and knitting into installation-art forms—we see a different kind of homage to place, too, and its craft traditions.

Doug Guildford’s crocheted sculptures find a home at the Coaker Foundation in Port Union, Newfoundland, during the Bonavista Biennale. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Doug Guildford’s crocheted sculptures find a home at the Coaker Foundation in Port Union, Newfoundland, during the Bonavista Biennale. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Some of the locals assisting with the Bonavista Biennale on site express enthusiasm about the art installations and their effects.

“We already had 40 people through here today, some from Wisconsin, even,” marvels Jessica, an energetic young local acting as an on-site interpreter for Laura St. Pierre and Jon Bath’s spectral installation piece at the historic Mockbeggar Plantation Fish Store. She is aiming, this fall, to move down to St. John’s to get her auto-mechanic’s license; but until then she is happy to be involved with the biennial: “It’s really great,” she said.

Certainly, tourism and culture is an increasingly important part of the Bonavista economy, which has been slow to recover since the 1992 cod moratorium—that was the biggest layoff in Canadian history, with over 30,000 fishers and plant workers from over 400 coastal communities in Newfoundland and Labrador simultaneously put out of work. In 25 years, those jobs have not yet come back.

Nowadays, Beaudette is one of many who believes tourism and culture to be a boon to the local economy—she herself runs an art space out of an 1880 saltbox house in Duntara, 2 Rooms, most summers, along with an artist residency program. (Further, the biennial itself is a 2 Rooms project.)

“We had to think, okay, how do you apply art as an economic stimulator here?” says Beaudette.

It’s notable that the biggest of the biennial’s art installations are also in less travelled parts of the Bonavista Peninsula, away from the tourist village hub of Trinity.

Toronto artist Iris Häussler’s project for the Bonavista Biennale involved capturing dust and debris from abandoned houses in the region and attaching it to translucent material; the work is installed at 2 Rooms in Duntara. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Toronto artist Iris Häussler’s project for the Bonavista Biennale involved capturing dust and debris from abandoned houses in the region and attaching it to translucent material; the work is installed at 2 Rooms in Duntara. Photo: Leah Sandals.

And yet there are reminders throughout the biennial, if you look for them, that culture isn’t something that needs to be “brought” to outport Newfoundland. It is already present in spades.

For instance, artist Pam Hall’s installation at Community Hall in the small town of Keels (population: 51) focuses on an encyclopedia of Newfoundland community knowledge she has constructed in collaboration with outport residents.

Among the topics on view: What Joe Reid Knows About Local Jams + Jellies. On Everyday Breadmaking and the Power of Memory. On Lacing and Filling Snowshoes: A Job for a Patient Man. What Fred Knows About Knitting Vamps.

“It’s a treat to be able to move towards new work in a different way,” says Hall, who is hoping to continue collaborating with folks around the bay, this time in Keels itself, to document more of this local knowledge over the coming month.

For another part of the Biennale, in Devil’s Cove, Hall is working with local lore in a more poetic fashion—converting old Newfoundland textiles into dozens of fish forms that swim in the island’s powerful winds and breezes.

Pam Hall’s outdoor Bonavista Biennale installation, in Devil’s Cove, suspends fish forms made from old textiles. Photo: Brian Ricks.

Pam Hall’s outdoor Bonavista Biennale installation, in Devil’s Cove, suspends fish forms made from old textiles. Photo: Brian Ricks.

Touring these art installations, another crucial issue about place and culture, economy and environment emerges: Namely, can an event like this actually happen every two years here, as is implied by the title?

The concern is not a passing one: this kickoff of Bonavista Biennale has received a variety of funding sources and support—including the community, remarkably, billeting all artists, for instance—but the project has also depended heavily on one-off project funding from the federal government’s official Canada 150 initiative as well as from the Canada Council’s one-off New Chapter funding.

“The title [the Bonavista Biennale] is partly Newfoundland sauciness and partly aspirational,” co-curator Grattan admits. “At the very least it will raise the profile and help other visual art things happen” in the area, she hopes.

Biennale co-curator Catherine Beaudette, for her part says that she hopes the event could survive in a less frequent form—a triennial, perhaps, “or maybe 10 or 15 artists rather than 26.”

Both Beaudette and Grattan also wonder about the possibility of following a more commonplace Biennale funding model, one that involves more international artists—as well as support from more international funding bodies.

Given that Bonavista is closer to Reykjavik, London and Paris than it is to Winnipeg, Vancouver and Calgary, perhaps more international funding isn’t as far fetched as it at first might seem.

Local teenager Daniel Fitzgerald acts an interpreter for the Bonavista Biennale at the community hall in Keels (population: 51). Photo: Leah Sandals.

Local teenager Daniel Fitzgerald acts an interpreter for the Bonavista Biennale at the community hall in Keels (population: 51). Photo: Leah Sandals.

In the end, however, there might be a kind of loss if future editions of the Bonavista Biennale pursued the usual-suspects, international-artist circuit rather than focusing on Newfoundland and Atlantic practitioners.

Though this biennial’s first edition has its downfalls—the relative lack of Indigenous artists from the Atlantic region, beyond Barry Pottle, is a huge one—it would be wonderful if it could, like a certain pale green chair perched on a certain grey rock in the middle of a certain outport Newfoundland cove, persist for a little while amid the waves.

A closeup of Doug Guildford’s crocheted sculpture in the Bonavista Biennale. Photo: Leah Sandals.

A closeup of Doug Guildford’s crocheted sculpture in the Bonavista Biennale. Photo: Leah Sandals.

This post was corrected on August 23, 2017. The original post incorrectly stated that there were no Indigenous artists from the Atlantic region in the Bonavista Biennale. In fact, there is one: Barry Pottle.

Will Gill’s installation for the Bonavista Biennale puts a green chair on a rock just off the coast of Maberly, Newfoundland. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Will Gill’s installation for the Bonavista Biennale puts a green chair on a rock just off the coast of Maberly, Newfoundland. Photo: Leah Sandals.