Studios are the heart of an art school. They are places to test ideas and work through problems, as well as to access space, specialized equipment, technical expertise, and peers and professors. This is where the magic of unstructured time and discussions reveals new inspiration. But how are tactile learning and studio practices being adapted when access to facilities is limited? While some art schools have opted to go completely virtual, others are holding a mix of online and smaller, in-person lessons with regulated access to studio space. Overall, it seems the emergent rule for art schools and art students is to try to anticipate uncertainty under pandemic conditions and be poised to readjust when necessary.

At the Alberta University of the Arts in Calgary, in-person access to studios, including fibre, glass, ceramics, printmaking and metalwork is currently overseen by expert technicians who teach and guide material processes. AUArts studio manager Tara Niscak has been involved first-hand in pivoting the school’s extensive facilities toward supporting students at a distance. “The technicians’ roles have changed dramatically. When the announcement came that we were all online in the fall with the potential to have some students come in, we started concentrating on how to support them in building their own spaces and on new resources,” Niscak says.

AUArts’s Studio At Home initiative has expanded into an opportunity to teach skills to simulate real working conditions, something students don’t often contend with until after they graduate. Instructional videos and online orientations walk students through how to set up and safely maintain a home studio; technicians hold weekly drop-in “Tech Talks” online; and the school started a resource they’ve been talking about for years, Studio A-Z, an internal online hub of crucial material knowledge from each studio program area. They also implemented more equipment rentals, as well as curbside drop-off services (for processes such as kiln firing and bronze casting), which Niscak sees as possibly continuing. “In some ways, COVID-19 has forced us to move into areas we’ve been wanting to go to, but haven’t had the chance to,” she says. “There are all sorts of students out there and different ways of wanting to work, why wouldn’t we support them if we can?”

“We expected students to take a gap year, with a drop of 40 per cent in enrolment, but it hasn’t happened,” says Ilene Sova, Ada Slaight Chair of Contemporary Painting and Drawing at OCAD University in Toronto. Instead, there were waitlists for fall classes. In virtual town halls held over the summer, Sova encouraged students to use this time—when they can’t easily find employment, travel or do many other things—as an opportunity to create work, earn credits and connect with their artistic community at OCAD. Rethinking materiality and resources has been key to continuing to create, including in Sova’s own art practice. OCAD courses shifted over the summer and fall to scale down projects for home studios and allow for DIY solutions like up-cycling materials from closets and painting with turmeric and coffee.

Sova is acutely aware of concerns around art materials in a pandemic, considering financial precarity (as part-time jobs continue to evaporate) and the possible safety risks of asking students to go to an arts supply store. Her approach included developing the interdisciplinary COVID-19 Responsive Art course, which tackles head-on the anxiety and isolation students can feel by asking them to put this crisis in context with both their own positionalities and those of artists in other crises throughout history. “Students are concerned about materials and grades, and instructors are taking into consideration those circumstances,” Sova says. “The materials and crisis should be connected…a traditional painting isn’t going to have as much conceptual impact now.”

“For students who are weighing whether or not to go to school, there’s something about education itself that is a creative endeavour…. The act of choosing to still learn and work through this pandemic is an act of creativity.” —Anaïsa Visser

Similarly, Working From Home, a new course taught by associate professor Michelle Forsyth, looks at the home as a “site of creative inquiry,” and at artists throughout history who were confined to smaller spaces, such as Frida Kahlo making art from bed. While adapting art school to the virtual realm is imperfect, Sova also recognizes how some online learning removes barriers to participation for students with different access needs or other responsibilities such as caretaking, or those who want to stay in and study from their communities. She suggests, “If we become more adept at this, the potential for our education to reach students who previously didn’t have access is huge.”

Anaïsa Visser finished classes for an MFA in film production and creative writing at the University of British Columbia in May 2020 and took that experience as a student into a teaching position at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver. Visser adapted the virtual summer production course Bring Your Own Device to be less focused on technical learning and more about finding modes of creative resilience. Students worked with the technology they had available and felt comfortable using, from mobile devices and tablets to DSLR cameras. Throughout the course, Visser encouraged students to find and develop stories to tell from within their immediate social circles and homes.

The central question for Visser, with these expanded technical and conceptual parameters, was how to teach young artists not only to stay motivated and innovate their practices in a challenging learning environment, but also to find solace in the work they’re making. “For students who are weighing whether or not to go to school, there’s something about education itself that is a creative endeavour, regardless of what you’re studying, but especially if you’re studying art,” Visser says. “The act of choosing to still learn and work through this pandemic is an act of creativity. I hope that as a result students will feel they are better equipped to overcome any discouragement.”

What is analog photography without its darkrooms? It’s been difficult for Andrew Wright, associate professor of photography and the current graduate program director in the department of visual arts at the University of Ottawa, and his now all-online students to lose access to these necessary facilities. But the circumstances have also presented new opportunities: “The first thing I had all my students do was turn their bedrooms, bathrooms or living rooms into camera obscuras so that they could experience a real analog image,” Wright says. With the help of studio assistants, he also made cyanotype paper for students to pick up or receive in the mail. To Wright, it’s a “happy irony” to return to some of the oldest photographic processes when nothing else is available, and to bring imagemaking back to the physical action of light—something his students have found a lot of value in during a time that is otherwise defined by digital screen–based learning.

For fourth-year sculpture student Asha Cabaca, restricted access to studios at York University’s School of the Arts, Media, Performance and Design in Toronto has meant converting space in her garage into a working studio. But this temporary set-up hasn’t been ideal without professors and technicians in the same room: “I feel like now we have to take more initiative to do what we want,” Cabaca says. “There’s been a lot of stumbling, but learning as well, and the professors have been trying to make it the best possible experience.” The biggest shift for Cabaca has been enrolling in elective courses, rather than the metalwork class she intended, for example. While challenging, this broadening of coursework across disciplines offers new perspectives that can in turn inform a developing art practice in unexpected ways.

Cabaca’s year-long Installation Art class, taught by York University professors Yam Lau and Brandon Vickerd, introduced her to interventionist strategies in her own work, such as creating raw-clay mushrooms and placing them in a park to document their disintegration. Vickerd, himself a sculptor, knew he couldn’t teach classes as he had previously. He refocused on the energized meanings of public space on a mass scale, from the pandemic to civil rights protests to the toppling of colonial monuments to using digital space as a forum for critical change. Vickerd has seen students respond to these new circumstances and considerations by distinctly shifting core ideas of whom their artwork is for, as compared to a year or two ago. One of his students, for example, works at a retirement home and explored interventions to help uplift that at-risk community during the COVID-19 lockdown. He’s also seen how students’ practices are being redefined when they can no longer solely identify and work within a specific medium or skill set. Conversations have moved toward a gift-economy model, with students working from gestures of goodwill and exchange.

“In institutions, it’s not often we actually get to think about what we do as an experiment,” Vickerd says. “I think in a lot of ways, as challenging as that is, it’s like returning art school and universities back to their core purpose—they were always about experimentation, failures and successes, and assessing why something worked and why something else didn’t.”

This article is adapted from “School Guide 2021: Art education in a time of unprecedented change,” a special section of Canadian Art’s Winter 2021 print issue, “Tangents.” Download a PDF of the complete guide now, or visit our School Guide page online, to read more

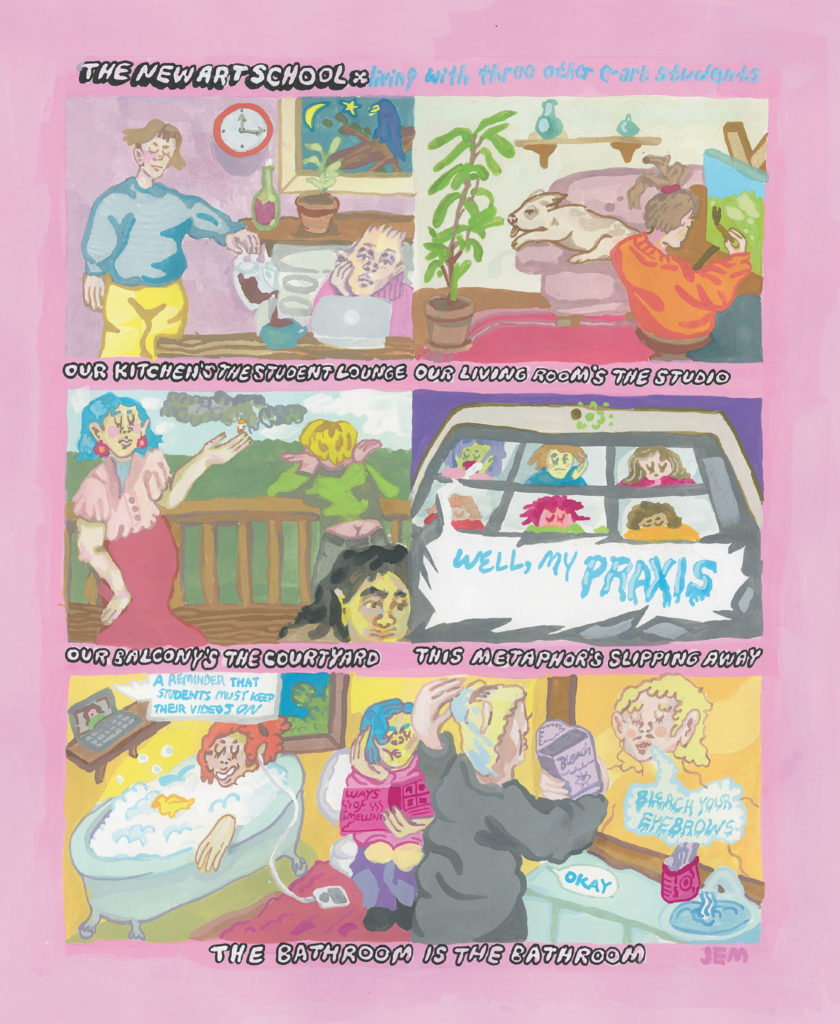

Jem Woolidge, The New Art School, 2020. Woolidge, an Interdisciplinary Arts major at NSCAD University, describes this image as follows: “Attending art school online during a mass quarantine has definitely been an adjustment. My roommates and I have been joking about the way we’ve unintentionally recreated the daily routines of an in-person learning experience, but at home. In a lot of ways, it’s like real school, though you can do it from the bath if you’re sneaky enough.”

Jem Woolidge, The New Art School, 2020. Woolidge, an Interdisciplinary Arts major at NSCAD University, describes this image as follows: “Attending art school online during a mass quarantine has definitely been an adjustment. My roommates and I have been joking about the way we’ve unintentionally recreated the daily routines of an in-person learning experience, but at home. In a lot of ways, it’s like real school, though you can do it from the bath if you’re sneaky enough.”