In a first this past October, the Universities Art Association of Canada held its annual conference online. The opening panel was “Accessing Art in the Virtual World: A Conversation about Access, Equity, and Diversity in 2020,” chaired by students Samantha Chang and Brittany Myburgh of the University of Toronto and Lauryn Smith of Case Western Reserve University/Cleveland Museum of Art. “Art history educators worked collaboratively in compiling lists of online resources to assist students and colleagues worldwide” in recent months, they noted. “Although the internet has helped many, the lockdown highlights significant connectivity and access inequality.” Just a few weeks earlier, in September, hundreds of artists, activists and scholars participated in the Scholar Strike for Black Lives in Canada to protest anti-Black racism and police brutality.

“I don’t think you can teach a class right now on anything—especially museums—that doesn’t take into account the current moment,” says Kirsty Robertson, director of Museum and Curatorial Studies at Western University in London. “One thing we have been doing [in class] is thinking about how museums might respond effectively to Black Lives Matter to move beyond a performance of care into some meaningful change.” The school’s Centre for Sustainable Curating also launched this year. “This moment has presented many opportunities to talk about how we can reduce the environmental impact of museum exhibitions,” says Robertson, “while also talking a lot about how we are using immense energy resources to be online.”

At the University of British Columbia, online panels, talks and conferences “are here to stay,” Critical and Curatorial Studies program director Scott Watson says. “They are easier to organize and less expensive, and easier on the planet.” At the same time, Watson notes, “people are hungry for an embodied experience.” A curatorial student who left during the spring lockdown is moving forward with her thesis show at the Polygon Gallery—even if she can’t be there. “We’re working from her SketchUp design and we’ll communicate with her on FaceTime to get the show installed,” says Watson. “That is unusual.”

Professor Jayne Wark, who’s been teaching art history at NSCAD University in Halifax for more than 30 years, can relate to this unusual, and often vulnerable, learning context. “The old pedagogy of teaching skills, like how you do your research, still comes into play,” says Wark, “but in the classroom, in designing the assignments, it’s a whole new game.” Wark has new technology and administration to manage, while her students process global crises in addition to their courseloads. To address that reality, Wark has reduced readings and assignments for all students; done one-on-one virtual calls with students for more in-depth catch-ups; and made small-group projects mandatory so that students have an impetus to connect, rather than isolate.

Indigenous art history education is changing too. Jackson Two Bears and Devon Smither of the University of Lethbridge and Open Art Histories recently facilitated “Land is Our First Teacher”: Teaching Indigenous Art Studio and Art History Online. The description for this interactive workshop promised to examine the risks and opportunities of the current era as “a starting point for developing strategies for creating

accessible, inclusive and active remote classrooms that position education as the vehicle for sustaining cultural knowledges.”

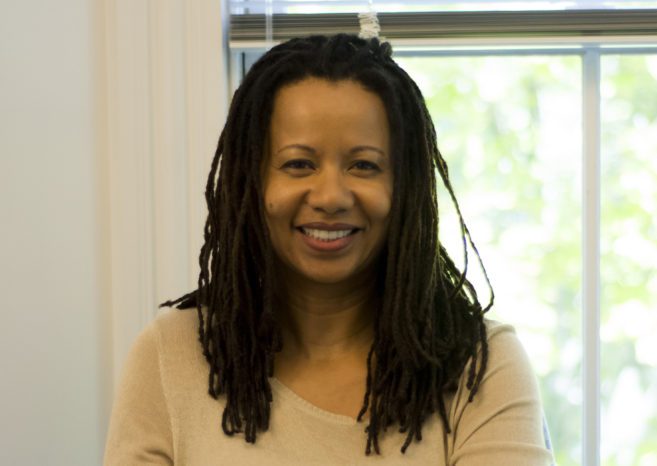

And, in June 2020, NSCAD announced that art historian Charmaine A. Nelson—Canada Research Chair in Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art and Community Engagement—will create the Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery. “There’s a 200-year history of slavery in this nation that has yet to be— even in any surface way—taken on or tackled by academics, or the lay public or the media,” Nelson has said. On her own website, Nelson maintains lists of key resources and archives for Black Canadian studies in the arts. “As I always say to my students, the fields of Postcolonial Canadian Studies and Black Canadian Studies are wide open,” she states, “especially as it concerns the discipline of Art History, which seeks to examine art and visual culture.”

This article is adapted from “School Guide 2021: Art education in a time of unprecedented change,” a special section of Canadian Art’s Winter 2021 print issue, “Tangents.” Download a PDF of the complete guide now, or visit our School Guide page online, to read more

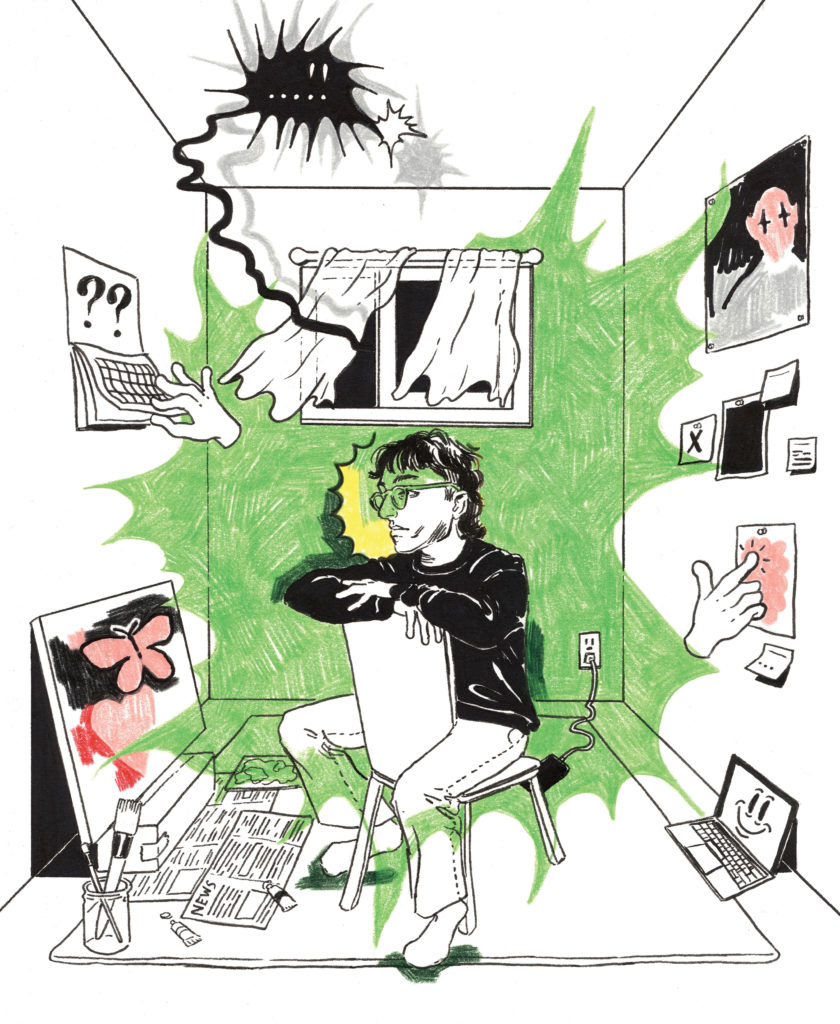

Ali Sheikh, Inside Out, 2020. Sheikh is currently enrolled in the Drawing and Painting program at OCAD University, he describes this image as being about “finding motivation in the home-studio

environment.”

Ali Sheikh, Inside Out, 2020. Sheikh is currently enrolled in the Drawing and Painting program at OCAD University, he describes this image as being about “finding motivation in the home-studio

environment.”