During childhood, I never knew if I was a first-generation or second-generation immigrant. No one else seemed to know either. For first-generation, the Merriam-Webster dictionary lists two entries: the first definition indicates one who is born in the country a parent immigrated to (me) and the second deploys the peculiar sociological term to label the foreign-born immigrant themselves (my Jamaican father, who might be considered a first or 1.5 generation, since his mother moved to Canada before him). The older I got, however, and the more kids I met at the Toronto District School Board schools I attended, the less such distinctions mattered. Having grown up in a country of enterprise, we automatically preferred being first over being second, so if anyone asked—which they didn’t—that’s what we were: first generation.

You might not ask Christopher Udemezue (Neon Christina) what kind of immigrant parlance he prefers, but he will tell you that he calls himself a first-generation Jamaican American. Born on Long Island, New York, the artist founded the collective RAGGA NYC, a platform that fosters community through dance parties (also known, to the initiated, as “bashments”), family dinners and art exhibitions. The collective describes itself on its website as “a hybrid of ideas that began as late night conversations over familial island roots, current social politics, empanadas vs. beef patties, pum pum shorts, scamming and a longing for an authentic dancehall party that provides for queer Caribbeans and their kin.” Also on the website are profiles of collective members—which includes DJs, writers, artists and educators—answering two simple questions: “How has your background affected your life/work?” and “What’s next for you (upcoming projects)?”

In a way, these two questions also guide RAGGA’s new show in Toronto, on view through August 11th. While RAGGA NYC began, eponymously, in New York City, the project has recently ventured north of the border for an exhibition at Mercer Union, an art centre in Toronto. Stressing chosen family over the performance of networking, and grassroots political organizing over fitting into a stale scene, the Toronto exhibition at Mercer Union includes artists Oreka James, Aaron Jones, Tau Lewis, Michèle Pearson Clarke, Martine Gutierrez, Sondra Perry, Diamond Stingily, Camille Turner, Christopher Udemezue and Syrus Marcus Ware. Some of these artists have defined themselves or their work as queer; others not so explicitly. Some of these artists live in Canada, but many live in the United States. Perhaps there is nothing specifically “Canadian” about this grouping, but indeed that might just be what Canada expects me to say: that we are all welcome, that we belong, that we are a “we.”

There is bliss in placing definitions aside while also foraging for meaning. So many of RAGGA’s works project the kind of understanding of the Caribbean I cultivated when I lived in Toronto—unstable and elastic.

There’s that tiresome war over food-metaphors: the culinary symbolism that pits Canada’s salad bowl against the USA’s melting pot. In the metropolitan cities of migrants in the U.S. and Canada, the metaphors are more similar than either country would admit. In each case, culture reigns over capital. I like metaphors so much—I live and work for them—but the salad bowl and melting pot become nothing more than superfluous celebratory signs that obscure the realities of North American society: incarceration, poverty, state violence, inequality, debt, and an endless et cetera.

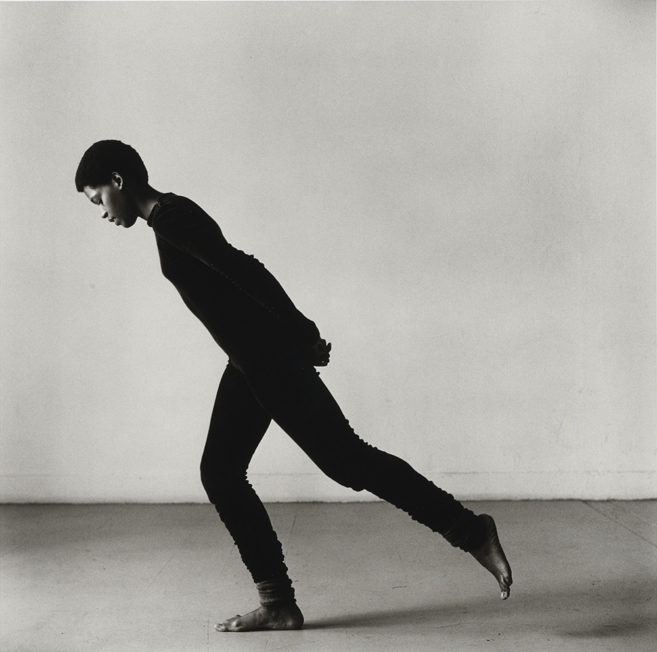

RAGGA’s Toronto exhibition has more of an aura to it than RAGGA’s New Museum exhibition last year. Here, the vibe is less sentimental, less neat, less facilely stamped as “queer Caribbean” because the show almost gives up on the term itself and turns, over and over again, toward practice. With the site of the Caribbean diaspora scattered further, now doubled to straddle the border, the artists in RAGGA NYC diverge tremendously in their art forms, as parts in any group tend to do. Trinidad-born artist Michèle Pearson Clarke is known for her video and photography work, and as part of the RAGGA exhibition, holds weekly sessions on Tuesday nights exploring transformative justice. And then there’s Oreka James’s oil, acrylic and cold-wax paintings—depicting subtly workerist body parts against rubbed-out backgrounds—hung on loose canvas; Sondra Perry’s photography exploring black women’s beauty through selfies and fake hair and nails; Martine Gutierrez’s hyperreal, full-color portraits of women posing in clothes that pays homage to Guatemalan textile traditions, which is taken from a series called Indigenous Women; Diamond Stingily’s 38-foot sculpture, which includes materials such as barrettes and a brand of hair extensions called Kanekalon; Aaron Jones’s collage installation signalling to a landscape of narrative; and more, always more.

From left: Tau Lewis, Seashell, 2018. Hand sewn fabrics, furs and leathers, hand carved plaster, acrylic paint, wire, stones, jute, hardware, sea shells, sea stones. 25 x 16 x 20 in. Courtesy the artist and Kai Exos; Tau Lewis, What in the water? (time capsule #3), 2018. Plaster bandage, cloth, plaster, acrylic paint, stones, foam sealant, secret objects 33 x 49 x 30 in. Courtesy the artist and Cooper Cole Gallery.

RAGGA constitutes a generation of artists whose sustenance is to link up for the sake of linking up. At Mercer Union, Tau Lewis’s sculptures touch each other: Seashell (2018) lies atop of What in the water? (time capsule #3) (2018). The title of Seashell—a doll-like figure made of, yes, shells but also a mixed-bag of found materials including fabrics, furs, leathers, plaster, acrylic paint, stones, and wire—might, at first thought, reference the supposedly pristine natural life of the Caribbean but instead, through simulation, re-signifies it. The works speak to each other, not necessarily to the viewers, just as the artists in RAGGA seem to wish to connect with others rather than an outside party.

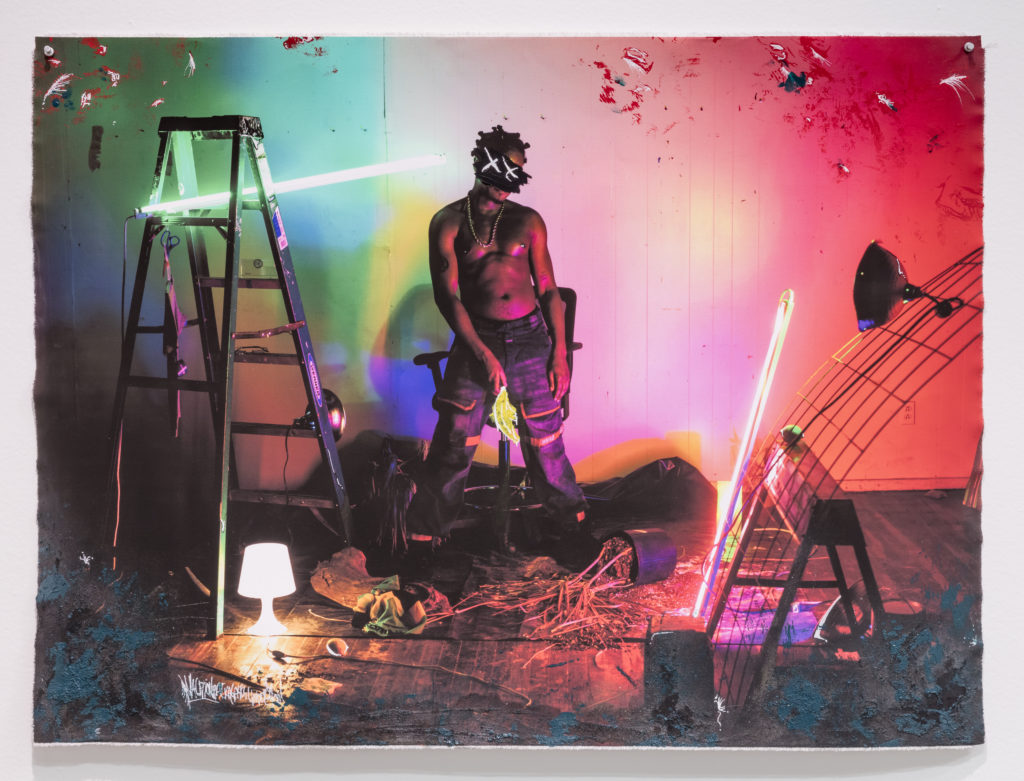

But others are watching. Udemezue’s mixed media on canvas, Untitled (underneath the palm tree leaves where they can’t find us) (2018), reframes the iconography of the Caribbean—say, something as brand-stamped as the blue Chiquita banana sticker or something as ephemeral as flora—and codes it in, parenthetically. In a recent interview on the radio show Know Wave, Udemezue’s brother Kenny Emez said “Homophobia—at least in our culture—and even where we grew up on Long Island, it’s just so taboo, no one talks about it. There will be a hundred lesbians but no one’s gay, there’s no gay men. It’s just like, wait a second…” RAGGA runs with our open secrets and thus insists that we do not always have to unpack the terms of the day in order to live them.

Like “immigrant,” “queer” is another English word that has ambiguous or, you could say, polysemous meanings, one that has no direct translation to the many languages spoken in the Caribbean (among them English, French, Dutch, and many forms of patois). Queer might mean a sexual or gender identity, a politics or an aesthetics but my point is that it’s a term that people quarrel over. In other words, it has been deemed a useful instrument of the contemporary moment. At the same time, however, it might make more sense to follow “ragga” rather than hold on tightly to the word queer, especially as the name of the collective indexes sound: the offbeat rhythms of reggae, the electronic keys of a Casio MT-40 synthesizer, Jamaican patois.

It is clear that for RAGGA, which in its exhibition description for the Toronto show calls itself as “growing collective of Queer Caribbean artists and allies,” queer is an ambiguous and thus capacious word. If everything can be queer, is anything queer? But the conjunction of “queer caribbean” is quite a different provocation, one with even less answers.

All that to say, don’t call on RAGGA to shore up your radical lexicon of queer, immigrant or Caribbean. There is bliss in placing definitions aside while also foraging for meaning. So many of RAGGA’s works project the kind of understanding of the Caribbean I cultivated when I lived in Toronto—unstable and elastic. I was Jamaican not because my dad lived there or because I worked at a weekly Caribbean newspaper or because I could claim knowledge of Little Jamaica on Eglinton West before gentrification. I aspired to be irreverent; I was Jamaican because I said so, because we said so among others who said the same.

“RAGGA NYC,” featuring work by Michèle Pearson Clarke, Martine Gutierrez, Oreka James, Aaron Jones, Tau Lewis, Sondra Perry, Diamond Stingily, Camille Turner, Christopher Udemezue and Syrus Marcus Ware will be on view at Mercer Union until August 11, 2018.