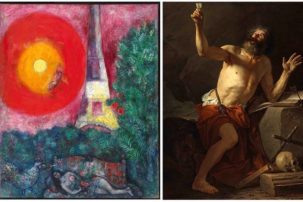

Recently, Christie’s New York sent out a press release trumpeting one of the key works in its upcoming May 15 auction of Impressionist and Modern Art: Marc Chagall’s 1929 canvas La Tour Eiffel (a.k.a. The Eiffel Tower).

A Chagall at a New York auction is not particularly newsworthy for most Canadians. But this one should be. Why? Because La Tour Eiffel is being sold by the National Gallery of Canada, which, since 1956, has held it in trust for Canadians within its public collection.

It is relatively rare for the National Gallery of Canada to deaccession works, and rarer still for it to deaccession ones of this prominence and market value at international auction. Here are a few things Canadians should know about the deaccessioning and sale of Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel from the National Gallery’s collection.

1. Proceeds from the sale of this Chagall—as required by National Gallery of Canada policy—will go back towards its acquisitions funds.

While some museums in the United States in recent years, like the Berkshire Museum, the Dia Art Foundation and the Delaware Art Museum, have deaccessioned and sold off artworks to try and pay off debts and keep doors open, that option is not available for the National Gallery of Canada.

According to what the NGC calls its dispositions policy, “any funds received from the disposal of a de-accessioned work of art will not be used for operations or capital expenses. Proceeds from the disposal are credited to the Director’s Acquisition Trust Fund for future purchases of works of art for the collection.”

In an emailed comment regarding the Chagall, the National Gallery of Canada underlined this policy: “De-accessioning allows us to refine, improve and add to our holdings, so that we may better fulfill the Gallery’s mission and serve the public. This process meets national and international professional standards, and follows guidelines set by, among others, the Association of Art Museum Directors and the Canadian Art Museum Directors’ Organization. All proceeds from the sale of de-accessioned works are used to purchase other works of art more suitable to the collection.”

2. The National Gallery isn’t selling the Chagall to generate money for acquisitions in general—rather, it is trying to obtain cash for acquisition of a specific work of Canadian art.

When asked for comment about the decision to sell this Chagall, the National Gallery of Canada provided a statement that included this sentence: “Proceeds from the sale will be used to purchase an important work that is a part of our national heritage.” Not several works—not works in general—but “an” important work. What that specific work is, though, the gallery isn’t saying yet.

Just to recap, here is the mandate of the National Gallery of Canada, which guides its collection activity: “The purposes of the National Gallery of Canada are to develop, maintain and make known, throughout Canada and internationally, a collection of works of art, both historic and contemporary, with special but not exclusive reference to Canada, and to further knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of art in general among all Canadians.”

3. The particular work of Canadian art that the gallery is looking to purchase with its Chagall auction proceeds is expensive.

For many years, the gallery has received parliamentary appropriations of $8 million annually for acquisitions. (The parliamentary appropriation for gallery operations, also fairly consistent, is an additional $37 million or so annually.)

According to the NGC’s most recent corporate plan, the appropriation amount for acquisitions is not projected to change, so the roughly $6 to $9 million USD that the gallery is hoping to receive for La Tour Eiffel is above and beyond the usual $8 million CAD it receives annually. This “important work that is a part of our national heritage” must be expensive indeed.

The acquisition may have come up quickly, too (or its funding gap did). The gallery’s most recent corporate plans, which extend out to 2020–21 fiscal year, do not include any budget line with an additional $7.7 million to $11.6 million in acquisition budget additions or variations.

4. There are only a few Canadian artworks publicly known to have purchase prices that would require the quick sale of a $6 to $9 million Chagall to fund them—but it’s also possible a commission is in the offing.

At current exchange rates, if the Chagall sells within estimates in New York, that would yield $7.7 million to $11.6 million CAD for the National Gallery to use towards acquisition of a single work. This amount would cover off the sale prices of what the CBC has called the “five most valuable Canadian artworks ever sold at auction”: Lawren Harris’s Mountain Forms, which went for $11.2 million in 2016; Jean Paul Riopelle’s Le Vent du Nord, which went for $7.4 million in 2017; Paul Kane’s Scene in the Northwest, which went for $5.1 million in 2002; Lawren Harris’s Mountain and Glacier, which went for $4.6 million in 2015; and Jeff Wall’s Dead Troops Talk, which went for $3.7 million in 2012.

But another option that is possible within NGC policy guidelines is for the gallery to commission a work rather than simply purchase a pre-existing work—and in this case, purchase price may be inflated or augmented by fabrication, installation and consultation costs. States the gallery’s acquisition policy: “The Gallery may on occasion commission works of art,” and in these cases, the total purchase price includes “costs of fabrication, technical consultation and installation, and any other related costs.”

A commissioning scenario may fit with some current contexts: National Gallery of Canada director and CEO Marc Mayer is soon finishing up his second five-year term, and he is known to be a big fan of large-scale permanent installations of contemporary art—as he demonstrated with the $1-million acquisition and installation of US artist Roxy Paine’s Hundred-Foot Line on the gallery grounds in 2011.

5. This Chagall had to be offered at market value to other major museums in Canada before it could be brought to Christie’s in New York.

National Gallery of Canada disposition policies detail that before bringing a deaccessioned artwork to public auction or private sale, the gallery must “first offer the work for sale by private agreement at fair market value to ‘category A institutions,’ as designated by the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board.” According to this list there are roughly 245 category A institutions in Canada, 160 of which are designated in particular for works of fine art. So 160 other museums and galleries in Canada were technically qualified to hold a painting like La Tour Eiffel in their collections—but none of them could either afford to or wished to.

Other major Chagall holdings in Canada are few, likely due to the high cost of these works. The Art Gallery of Ontario has the 27-by-25 inch oil-on-paper painting Over Vitebsk (1914). The Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec has the litho print Le Cheval Rouge (ca. 1958) and the litho print Maternité (1926), as well as the litho print Boulevard Massina, de la série «Nice et Côte d’Azur» (1967). There are more, of course, but few large-scale works among them.

6. This deaccession may disappoint Chagall fans in Canada, given that there is only one other Chagall painting remaining in our national collection.

It is almost certain that Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel—in the country since 1956—will be leaving Canada permanently once it heads to New York for auction, as it’s only international collectors and museums who will likely be able to afford it.

And there are Chagall fans in Canada out there to be disappointed. From January 28 to June 11, 2017, the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal exhibited “Chagall: Colour and Music,” the largest exhibition ever devoted to Marc Chagall in Canada; it had a total attendance of 302,992, making it the fifth most heavily attended exhibition in the history of the MBAM, itself Canada’s most popular art museum.

7. However, the National Gallery contends that even with this deaccession and sale, its Chagall holdings remain strong.

In an emailed statement, the National Gallery states that “The Eiffel Tower, dated 1929 (oil on canvas; 100.0 × 81.5 cm), was purchased in 1956, at a time when the Gallery was building its Contemporary and Modern European art collection. Since then, the collection has been further enriched, and this one work has become less relevant to our needs.”

The statement continues: “The sale of The Eiffel Tower will have no effect on the Gallery’s commitment to preserving, studying and displaying Chagall’s art. The Gallery retains an outstanding painting by the artist: Memories of Childhood from 1924 (oil on canvas; 73.8 × 86.3 cm), the generous gift of an anonymous donor in 1970. The Gallery also has a large and important collection of Chagall’s prints and drawings, which provide context for the painting.”

8. The choice of La Tour Eiffel for deaccession and sale minimizes administrative obstacles to deaccessioning while maximizing financial returns.

There are many conditions in the National Gallery of Canada’s disposition policies that can make certain works more difficult to deaccession. For instance, the NGC cannot deaccession works by living artists. The policies also note that where works were donated to the gallery by gift, transfer or bequest, the gallery must contact a donor or the donor’s remaining family or estate to clear the disposal with them. And the sale must result in an improvement to the collection, which (quite sensibly) prioritizes Canadian art and Indigenous art over American and European art.

In the case of La Tour Eiffel, no such donor consultation or permission was needed, as the gallery purchased the work directly from Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York in 1956. And deaccessioning a work of European art to acquire something Canadian or Indigenous meets collections criteria easily.

And in terms of market value, Chagall’s star is rising fast. Just a few months ago, on November 15, 2017, Chagall’s Les Amoureux (1928) broke an auction record for the artist when it was hammered down for $28.5 million at Sotheby’s in New York. Though somewhat different in subject matter, La Tour Eiffel was painted just one year after Les Amoureux, in 1929. It is of only slightly smaller scale: La Tour Eiffel is 100 centimetres by 81 centimetres, while Les Amoureux is 117.3 by 90.5 centimetres. And La Tour Eiffel, while dominated by architecture of its titular tower, does in its lower third depict the artist’s wife Bella, who was a central figure of Les Amoureux and other iconic Chagall works.

As Christie’s own deputy chairman of Impressionist and Modern art, Cyanne Chutkow, stated in a press release, “This painting is being offered for sale at an ideal time in the market, when singular examples by Chagall are in more demand than ever.”

9. La Tour Eiffel is now on view in Hong Kong, and is headed soon to New York.

La Tour Eiffel is already on the road for Christie’s as the auction house tries to generate bidder interest. Until April 4, it is at the Hong Kong preview for Christie’s May 15 Impressionist and Modern Art sale, specifically at the James Christie Room, 22/F Alexandra House, Central, Hong Kong. Entry is free and open to all—if you can get there.

At press time, Christie’s representatives stated that La Tour Eiffel may be going on view in New York in late April during its auction highlights view, but that is not confirmed yet. The only date for certain it will go on public view in NYC is during the preview of all auction lots on May 12, 13 and 14 at Christie’s headquarters in Rockfeller Center.

Also worth noting: More information about the work and its sale will come to light when the Christie’s auction catalogue becomes public in mid-April.

UPDATE: Want to know what else the NGC is deaccessioning right now? See our roundup post.

Marc Chagall's La Tour Eiffel (1929) is being sold by the National Gallery of Canada at Christie’s in May—and it's the highest-profile deaccession the gallery has done in decades.

Marc Chagall's La Tour Eiffel (1929) is being sold by the National Gallery of Canada at Christie’s in May—and it's the highest-profile deaccession the gallery has done in decades.