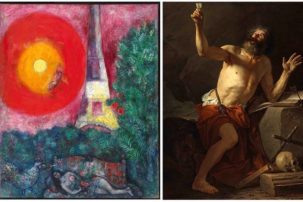

What does a public art institution owe its publics in terms of transparency and communication? What does a gallery director do when one of the very reasons they are deaccessioning a painting—its high market value—also causes considerable public attention, concern and controversy? These are some of the questions that have come to a head around the National Gallery of Canada’s process of deaccessioning Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel in an attempt to acquire David’s Saint Jerome. Here, in a condensed version of a phone interview that took place yesterday afternoon, NGC director and CEO Marc Mayer explains his perspective.

Q: I want to start out with some context. During your decade at the National Gallery, much has been accomplished: reviving the Canadian Biennial, restoring the Venice Pavilion, starting an Indigenous quinquennial, integrating the Indigenous and Canadian collections. But the recent Chagall deaccessions decision has proved quite controversial. I’m wondering what you feel you have you learned in your time at the gallery. Also: What is your hope for the coming months as you finish up your work there?

A: I’d like to see the drama kind of calm down a little bit. All we are saying is we are making sure this extraordinary work [the David] doesn’t leave the country. We are not robbing anybody. We are protecting Canada’s national heritage and we are proud of that. We are going the extra mile to do it.

I am shocked I am being called the big bad wolf. I think cooler heads will prevail.

Q: And what have you learned in your time there?

A: I have learned that you can transform a large old public institution. You can make it more relevant to the present. It’s hard work—and maybe it’s maybe harder for a museum of this nature, which is a crown corporation. But it is possible.

But I’m not out of the job yet. I have about another 10 months to go. And if you ask me the same question a few years from now, it might be a different answer.

Q: It’s interesting you mention bringing an old institution into the present day, because one of the things that has changed over the years, I think, is that people expect much more transparency now from their public institutions. On that note, the disposition policy for the National Gallery of Canada states that “Attention will be given to transparency throughout the process.” And the Association of Art Museum Directors deaccessioning policy, which I know the NGC policy refers to, says, “Attention must be given to transparency throughout the process.” (Italics mine.) Can you please tell me how that attention to transparency was actually given in regards to the deaccession and disposition of Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel?

A: We sent out a letter to over 150 of our museum colleagues in Canada with a JPEG of the Chagall and with some copy telling them we were deaccessioning this painting.

That was four months ago, and it didn’t say “Confidential” anywhere on that letter. We didn’t get responses from anyone, and it didn’t get passed on to the press. And none of my colleagues called me up to say, “What on earth are you thinking?”

So that was as transparent as we should get.

We are not working with our acquisitions and deaccessions in the public domain. If we did that, we would have people saying, “I don’t like this, I like that.” You can’t run a museum by plebiscite.

Four months ago we gave people a heads-up; we gave them deadline of January 9 to get back to us, and then we gave Christie’s the go-ahead.

But no, we would not send out a press release [about the Chagall deacession ourselves], or releases following these things that have been in storage. Some people have plenty of opinion, but not much knowledge.

Q: So let me make sure I’m clear on the chronology here. The board of trustees voted to deaccession the Chagall in December 2017. Then, as your disposition policy specifically requires before bringing a deaccessioned work to sale or auction—and that is not noted in the policy as being for transparency reasons—you notified all other Category A institutions in Canada that the work was available for purchase. And you gave those museums a response deadline of January 9? So they had a month or less turnaround time to respond?

A: Around a month. And we consulted with the people who we think should have been consulted.

Most of the loan requests we have had for that Chagall have been from Japan. So I was kind of not surprised by the silence that I got from my colleagues [at other Canadian institutions after sending them that notification].

But I am certainly surprised by the reaction today. That is a very different scenario than I had pursued.

Q: So you didn’t foresee this Chagall deaccession, or communications decisions around it, as being problematic with the public?

A: No. And the reason we couldn’t tell anyone [about the David acquisition hopes] is because M. Bélanger [with the Notre-Dame parish, which owns the David] had asked us, begged us, for our discretion, because he had not yet received permission from the Vatican to sell the work.

So we were not going to be risking our chances for them or us—we weren’t being sneaky about that.

Q: I understand regarding the acquisition confidentiality. But I would like to focus back on the Chagall for a moment. The disposition policy for the National Gallery of Canada also states that “De-accessioned works will be listed in the relevant Annual Report, with the method of disposal and outcome noted. In addition, this information will be posted on the Gallery’s public website.” On April 3, some four months after the Chagall was deaccessioned by the board of trustees, and some two weeks after the Christie’s press release regarding Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel came out, La Tour Eiffel was still listed on the NGC website as belonging to the NGC collection. Why was the information not posted on the website as policy indicated, whether in the artifact record or by any other means?

A: We are very challenged with the website. It takes a lot of people to manage. It’s not the most up-to-date website in the world.

I mean, Louise Bourgeois had been dead a year and a half before we updated the [biography] dates on our website.

That has been challenge for us to be sure.

Q: I know the Annual Report only comes out in December, but internally you were clear the Chagall—and eight other objects—had been deaccessioned in December 2017. Why is this deaccessioning information not yet posted to the NGC website as required by policy?

A: Well, the policy talks about method of disposal and outcome information [too]. And the method and outcome part of the story are yet to come.

And our annual report, of course, has a number of other hands on it, and many editorial revisions before it gets made public. This is why, when we have the annual public meeting, we never have the report in hand; they are not ready.

Our schedule for AGMs have never lined up with the government’s [review] schedule. So we only have the previous year’s report there.

Q: Ok, again, just for clarity: This Chagall deaccession happened in December 2017, and the only place the policy requires this information to be in print is in the Annual Report, which doesn’t get released until December 2018.

A: Yes, it will be in the annual report coming in December 2018.

Q: According to the mission statement on the NGC website, one of the six key values of the NGC is collaboration. It states: “The Gallery collaborates with the network of art museums in all regions of Canada and abroad, and with its partners in the Government of Canada.” I know in the past you have co-acquired major works like The Clock with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, as well has had close collection-sharing arrangements with the Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton and the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto. Given both policy and precedent around the value of collaboration, can you tell me why you are unwilling to collaborate with other Canadian museums on a David acquisition?

A: Because it’s unrealistic to share the acquisition of an Old Master painting.

Yes, we have collaborated—buying a half-interest in The Clock, a video and installation work. And that was exceptional. Our trustees so far as I have been here have not been interested in co-ownership for the most part.

And Old Master co-ownership is extremely rare. I know M. Bondil [of the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal] says she knows of one example, but I’m not sure what it is.

Co-ownership is very expensive—it’s expensive to pack up works and ship them between museums. And we wouldn’t lend this [David] to any old exhibition; it would have to be a scholarly, serious show. It’s a 250-year-old canvas with paint on it.

Q: One thing I don’t understand is that the three Canadian institutions interested in acquiring the David have already, to an outsider’s eye, been effectively sharing the work. The NGC had it on display for 18 years, then the Musée de la civilization à Québec, which was shepherding it, asked for it back. Now, it’s on display at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal. If you have already been shipping the work back and forth amongst yourselves, what is the problem with continuing to do that?

A: We asked to borrow [the David] on long term—18 years!—then they asked for it to be returned, and it went back into storage. And it reemerged in Montreal as a loan from the Musée de la civilisation when it became available for sale. So it has not been shared. It was 18 years on our wall otherwise it was in storage.

[As to whether the other museums would like to collaborate with us on a co-acquisition] I have no idea, because they never did call me.

What I do know is that that M. Belanger approached us saying there didn’t seem to be any possibility in Quebec for the David to be acquired. And then we had this communication with my colleagues abroad—more than one institution—and they were saying, “We are interested in acquiring this painting, is it going to get held up in Canada? Are you going to be able to export this thing? We want more information before we consider it for acquisition.”

So that is really the story.

Q: We have already gone over time for this interview, so thanks for your patience. Here is the final question: I realize you must have felt concerned about the painting leaving Canada when you heard from your colleagues overseas that they were thinking of acquiring the David. Why, though, did you not return to the seller, M. Bélanger [of the Notre-Dame de Québec church], and ask him if he was serious about doing such a sale overseas? Recent reports in Le Devoir suggest that he said he wasn’t interested in selling overseas. Why did you rush to deaccession the Chagall before checking that the information you received was accurate?

A: Well [I think M. Bélanger knows] the David is not going overseas now, that’s true, because we are going to be selling our Chagall. Now, he is in no fear of that.

What you’re suggesting—well, I don’t want to call him up and threaten him! This thing has been for sale for almost two years, Leah. He has been very, very patient with all of us to try to fund this acquisition. We know he was talking to foreign museums.

Q: I don’t mean threatening a person. I mean asking a person if information is accurate.

A: Oh, “We have it on good authority ….?” How do you frame that? And embarrass him, [potentially]?

I also wasn’t involved in these conversations at the time. This was being negotiated by one of our curators.

Q: Chief curator Paul Lang?

A: Yes, who has left to run museums in Alsace. I wish him well with that.

Q: Well, I know you have plenty of people to speak with and we have gone over time. Thanks for this, Marc.

A: Thanks, Leah.

This interview has been edited and condensed. Interested in reading more coverage of the Chagall-David story? Try some of our prior articles, like “What to Know About the National Gallery’s Latest Chagall-David Move,” or “Can Deaccessioning Become More Transparent?”

Marc Mayer at the National Gallery of Canada, June 2014. Photo: Tony Fouhse.

Marc Mayer at the National Gallery of Canada, June 2014. Photo: Tony Fouhse.