Overall, it’s quite a timeline—one that has kept Canadian art-world watchers on the edge of their seats.

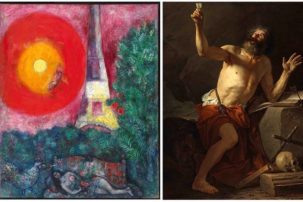

On March 21, Christie’s issued a press release stating that the National Gallery of Canada had deaccessioned Marc Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel (1929). The next day, the NGC disclosed via email to Canadian Art that the sale was being made to acquire a specific work of national heritage value. On April 4, the CBC made public that the Chagall was part of a wider gallery deaccessions trend. On April 10, Agence QMI broke the news that La Tour Eiffel was being sold to get funds to purchase Jacques-Louis David’s painting Saint Jerome (1779) from the Notre-Dame de Québec parish.

And yesterday, April 16, saw another new and significant milestone in this story: the National Gallery of Canada—after repeated media requests and public petitions made in recent weeks—finally issued its first mass media release about its Chagall sale and related reasoning.

“Our decision to part with the Chagall was not made lightly,” gallery director and CEO Marc Mayer states in the letter which was mass-emailed to press and selected publics—and is available to read in full at the end of this post. He also states: “The National Gallery of Canada’s ardent goal since learning that David’s Saint Jerome Hears the Trumpet of the Last Judgment was for sale has been to acquire the painting.” (The latter point is perhaps not a surprise for anyone aware of David’s prominent place in the traditional Western art canon, and the rarity of his works coming to market.)

Here are some things to know—and question—about the letter.

A Gesture Towards Transparency

The April 16 letter can be read, in part, as a welcome and much-needed gesture towards increased transparency at the gallery, as it details the NGC’s rationale for acquiring the David, its related rationale in pushing the Chagall quickly to sale, and a chronology of the events from the gallery’s perspective.

An Explanation of Why the NGC Thought the David Was Leaving Canada

In fall 2017, the letter contends “the Gallery … learned from two foreign museums that they had been approached to gauge their interest in acquiring the David. One of those museums told us they were indeed very interested in purchasing Saint Jerome and had the funds to do so. We then understood that the risk to Canada of losing this national treasure was real, adding urgency to the matter. We began to explore other options [beyond private fundraising], such as selling a high-valuation work of art.”

While this explanation is helpful in terms of insight into perceived institutional urgency, it also raises questions.

Why? Because an April 12 Le Devoir article, based in conversations with Notre-Dame de Québec parish spokesperson M. Bélanger, indicated that the David painting was actually not in danger of leaving Canada—that is, that the parish did not intend to sell it outside of Canada.

If the National Gallery thought there was a possibility of the painting leaving Canada, why would it not check with the sellers at Notre-Dame de Québec that this was truly still on the table before launching into a major Chagall deaccessions process?

An Indication that Collaborative Acquisition Not Explored—As of Yet

The letter admits that “In July 2016 the Assemblée de fabrique de Notre-Dame de Québec offered Saint Jerome to three leading Canadian museums, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Quebec, and the National Gallery of Canada.”

This admission prompts a question: if the National Gallery of Canada knew the painting had been offered to two other Canadian museums, and if the National Gallery of Canada also knew it did not have the funds to acquire the David on its own, why did it not approach the other museums to possibly collaborate on an acquisition to keep the work in Canada while also retaining its Chagall?

The National Gallery is no stranger to joint acquisitions of rarer, in-demand works; as recently as May 2011, and under Mayer’s leadership, it co-acquired an edition of Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010) with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. This point, however, was not mentioned in the letter.

An Argument for Why the David Belongs at the NGC—Without Acknowledgement of Alternatives

Interestingly, while the letter from Mayer concedes the Musée de la civilisation à Québec’s right of first refusal on the David, the National Gallery’s letter might also seem specifically constructed to make a case for why the David should find a permanent home in Ottawa rather than in Montreal or Quebec City.

“Not only does the Gallery own the only other painting by David in a Canadian museum—a small, informal portrait of his brother-in-law (Pierre Sériziat, 1790, acquired in 1964)—the collection also includes works from his major contemporaries, as well as his most accomplished students,” the NGC letter states. It also argues that the National Gallery’s collection of French painting and Carravigisti (David painted Saint Jerome in Italy) is a reason it should be a particular fit at the NGC.

Nowhere in this letter is an acknowledgement of the work’s provenance and the way that that provenance relates specifically to Quebec City. The French immigrants who donated Saint Jerome to the church there already have the entire rest of their collection held at the Musée de la civilisation à Quebec—the institution which has also stewarded the work for decades.

A Decisive Statement that the Chagall Sale Will Go Forward Regardless

“Even if the Musée de la civilisation purchases Saint Jerome, the sale of [Chagall’s] The Eiffel Tower will proceed as per the rigorous de-accession process,” the letter from Mayer states. “The proceeds from the sale will be used to improve the national collection and, especially, to strengthen Canada’s ability to protect its patrimony from exportation, a challenge it will surely face again.”

A Hint at the Power of Outside Advisors at a Public Institution

“In December 2017 our Board of Trustees voted to de-accession and sell The Eiffel Tower by Marc Chagall, a picture we purchased in 1956,” the letter states. “In 1970, the Gallery was given Memories of Childhood, an earlier work by Chagall, which is more appropriate in the context of our strong collection of modernist works than The Eiffel Tower.”

Mayer frames the decision-making process as being directed by a certain group.

“Given the healthy market for works by Chagall, the staff, the Board and its external advisors, a group of five art historians, believed that it was the surest way to raise enough money to purchase the Saint Jerome within the given timeframe,” Mayer states.

The group of five art historians, all external advisors, that Mayer refers to are those who have been appointed as advisors to the board’s acquisitions committee.

While all are, in fact, PhDs in the study of art and art history, and all are learned, it’s worth noting that as externals the level of public responsibility and accountability they are tied to is likely less than that of NGC staff or trustees.

Also worth noting is the fact that due to board attrition and turnover issues—issues exacerbated by held-up processes at the Department of Canadian Heritage—the acquisitions committee itself was likely not at its full complement of trustee members when the acquisitions committee (with its advisors) recommended that the board deaccession the Chagall.

Beyond the Letter: Institutional and Public Responses

Canadian Art reached out to three stakeholders—the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, where the David is currently being exhibited; the Musée de la civilisation à Québec, which has been stewarding the David for years; and the creator of a Chagall-related petition—for their views on the letter.

(The Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal and the the Musée de la civilisation à Québec are currently working on a joint offer to purchase the David, with a deadline of mid-June.)

Here is some of what they had to say.

“I would say that it’s true that different museums abroad would be interested to have such a [David] painting, because it’s a very important one by a great artist, and David paintings are rare on the market,” said Natalie Bondil, director of the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, in a phone interview Monday evening. “But I’m sure that there are so many other solutions which were not tried” rather than selling the Chagall to acquire the David.

In particular, Bondil highlighted the collaboration that her museum and the Musée de la civilisation à Québec are engaged in as a way to keep the painting in the country.

“We do not want to compete with each other,” says Bondil. “We want to work in the spirit of transparency and collegiality as Canadian institutions.”

“I think we will be stronger together,” Bondil concludes. “Collaboration is the best way—but you cannot collaborate with someone without them being willing.”

The Musée de la civilisation à Québec indicated that it remains open to conversations with the National Gallery of Canada—while also hoping that the David can retain its provenance tie to Quebec City.

“[We hope] to maintain the Saint Jerome in Quebec and thus to keep the links with the community where the artwork was known to the public,” says Agnes Dufour, press liason for the Musée de la civilisation à Québec, via email on Monday afternoon.

Dufour adds that “Both museums [Montreal and Quebec City] are open to discuss a common avenue with National Gallery of Canada.”

But much in the letter still concerns art-lover Natasha Abramova, who in early April started circulating a Change.org petition to stop the Chagall sale.

Abramova in particular is concerned that, according to the letter, other public institutions in Canada only had a brief period of time in December and January to assemble a bid on the Chagall and keep it in Canada.

“Four months ago [December 2017] was pre-Christmas time,” Abramova states via email, arguing that holiday vacations for government and others only offered “a very short period of time—two to three months—when Canadian arts professionals were aware of this opportunity to purchase Chagall’s painting and keep it in one of the Canadian museums…. This is not sufficient time period to make a conclusion that ‘nobody’ would like to purchase [the Chagall].”

Abramova also remains disappointed that while the letter argues all private donor avenues were explored, “there were no attempts done to start a crowdfunding campaign and gather funds to buy out David without selling Chagall.” (Though the NGC has never done crowdfunding, it’s not such a far-fetched proposal: the UK’s National Gallery managed, with a major public appeal, to raise enough funds to keep Raphael’s Madonna of the Pinks in-country in 2004.)

The effect of the gallery’s letter seems, for her, to be mixed.

“A good thing about this release is that there will be no rumors anymore” about the work being acquired, says Abramova of the NGC letter. “However, there are many bad or pending things about this explanation.”

Read the Full April 16 Letter from the National Gallery of Canada

A message from the National Gallery of Canada

April 16, 2018

The National Gallery of Canada has now received permission from the owners to reveal the identity of the artwork we plan to acquire with the proceeds from the sale of The Eiffel Tower by Marc Chagall.

Saint Jerome Hears the Trumpet of the Last Judgment, painted in 1779 by Jacques-Louis David, is the work in question. It had been on view in our galleries for eighteen years, from 1995 to 2013, until the Musée de la civilisation in Québec City requested its return.

The National Gallery has the most comprehensive collection of French art in Canada with major works from the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries; a glaring exception is an important picture by David, a key figure in French art.

Acquiring the Saint Jerome painting would enhance our collection in very important ways. Not only does the Gallery own the only other painting by David in a Canadian museum — a small, informal portrait of his brother-in-law (Pierre Sériziat, 1790, acquired in 1964) — the collection also includes works from his major contemporaries, as well as his most accomplished students. To adequately represent this insurmountable exponent of Neo-Classicism would be a boon to any collection of European art.

The Gallery possesses, moreover, a strong collection of works by artists known as the Caravaggisti, painters who fell under the influence of the great Caravaggio, beginning in the early 17th century. Saint Jerome was painted by David in the 1770s, when he was living in Rome. The influence of Caravaggio’s art is unmistakable in this work, which would cap off nearly two centuries of such examples in Canada’s national collection, increasing its educational value.

Saint Jerome was among the very first paintings by the great French artist to reach North America, arriving in the late 19th century. It has been in Québec City since about 1917 and was donated to the Cathedral-Basilica of Notre-Dame de Québec in 1938. Over the last decades, its owners recognized the challenges of exhibiting and preserving a masterpiece of this calibre, and entrusted it for safekeeping to the Musée de la civilisation where it remained in storage until the Gallery requested its long-term loan for public display in 1995. During those years it was enjoyed by thousands of visitors.

In July 2016 the Assemblée de fabrique de Notre-Dame de Québec offered Saint Jerome to three leading Canadian museums, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Quebec, and the National Gallery of Canada.

From the time we were offered the painting, the Gallery had explored ways to finance the purchase. The price of Saint Jerome would have largely depleted our acquisition allotment, compromising our five other collecting areas for an entire year. By the fall of 2017 the Gallery had still not been successful in attracting support from within our network of private donors. Although Québec City’s Musée de la civilisation has first right of refusal until mid-June 2018, to our knowledge, they had not expressed an interest in purchasing the David painting.

At this time, the Gallery also learned from two foreign museums that they had been approached to gauge their interest in acquiring the David. One of those museums told us they were indeed very interested in purchasing Saint Jerome and had the funds to do so. We then understood that the risk to Canada of losing this national treasure was real, adding urgency to the matter. We began to explore other options, such as selling a high-valuation work of art.

In December 2017 our Board of Trustees voted to de-accession and sell The Eiffel Tower by Marc Chagall, a picture we purchased in 1956. In 1970 the Gallery was given Memories of Childhood, an earlier work by Chagall, which is more appropriate in the context of our strong collection of modernist works than The Eiffel Tower. Given the healthy market for works by Chagall, the staff, the Board and its external advisors, a group of five art historians, believed that it was the surest way to raise enough money to purchase the Saint Jerome within the given timeframe.

Four months ago, The Eiffel Tower was offered at fair market to more than 150 art museums across Canada. Since no museum or gallery responded to the Gallery’s offer, we entrusted the Chagall to Christie’s, the auction house that we believed was best placed to help us obtain the highest return on the sale.

Our decision to part with the Chagall was not made lightly. As it does with its acquisitions, the Gallery follows a rigorous process when de-accessioning works of art from its collection. We were supported by the team of outside experts mentioned above, who the Trustees enlist to test management’s proposals to refine the national collection as we work to ensure that it remains relevant to Canadian needs and continues to improve.

Saint Jerome Hears the Trumpet of the Last Judgment requires significant restoration. Our state-of-the-art conservation laboratories and our team of picture restorers are superbly qualified to bring this national treasure back to its former glory. Our collection of French art from the Neo-Classical period has grown remarkably since 2013, when this picture left our walls, with the addition of major works by Prud’hon, Vigée Le Brun and Meynier. Such recent additions provide an even stronger context for the display of this remarkable work by David, the artist of record for the period.

The National Gallery of Canada’s ardent goal since learning that David’s Saint Jerome Hears the Trumpet of the Last Judgment was for sale has been to acquire the painting. Doing so would enhance the national collection dramatically – a collection that is made available to sister art museums across the country through our generous loan program. Of equal importance to the Gallery is that a work of this magnitude not leave Canada. That will continue to be our priority.

Even if the Musée de la civilisation purchases Saint Jerome, the sale of The Eiffel Tower will proceed as per the rigorous de-accession process. The proceeds from the sale will be used to improve the national collection and, especially, to strengthen Canada’s ability to protect its patrimony from exportation, a challenge it will surely face again.

Marc Mayer

Director and CEO

National Gallery of Canada

—

A correction was made to this post in April 17, 2018. The original copy indicated that the David was recently on display at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal. In fact, it is currently on display there. We regret the error.

A view of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Photo: Twitter.

A view of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Photo: Twitter.