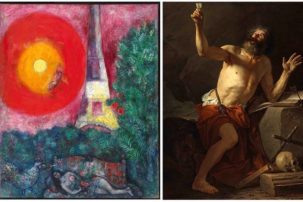

On Thursday—after weeks of public outcry, and also what the Globe and Mail reports was a “heated” board of trustees meeting on Wednesday evening—the National Gallery of Canada officially announced that it would be pulling Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel from a May 15 Christie’s New York auction.

The board’s Wednesday decision was a triumph for many Chagall fans across Canada, especially the ones who had been petitioning the gallery and the government for a reversal—a reversal that comes at no small cost, being estimated at some $1 million in auction-withdrawal fees.

But there are many reasons the Chagall debacle still matters.

It should still concern many folks, both in and out of arts-policy-wonk circles, that a gaffe of this scale happened at Canada’s national art museum—which also happens to be Canada’s best-funded art institution, to the tune of at least $48 million in federal appropriations per year—and that seemingly all along the way, many measures for both accountability and transparency were either weakened, refused or resisted at multiple points.

Also: This turn of events does not bode well for how other operations at the NGC have been managed in recent years, so anyone who wants our national gallery to do a better job in any part of its mandate needs to pay attention to the failure and fallout here.

Currently, some pundits are calling for National Gallery of Canada director Marc Mayer to step down, or speculating that the board will ask him to do so in advance of his early 2019 retirement plan.

But whether Mayer (who definitely has responsibility to bear here) stays or goes in the short term, there remain systemic issues around accountability, transparency and museum governance—both at the individual museum level and the federal government policy and practice level—that contributed to this irresponsible and costly course of events around Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel, the National Gallery of Canada, and David’s Saint Jérome.

Here are five of the outstanding issues that I think need to be addressed so that this type (or at least scale) of national art scandal doesn’t happen again, no matter who the director of the gallery is. In the coming weeks, I look forward to my colleagues at this and other publications sharing more perspectives on what needs to happen at the gallery moving forward.

1. The federal government’s Ministry of Canadian Heritage needs to take responsibility for its partial role in this matter—namely, dragging its heels in its task of ensuring that every national museum in Canada has a full, complete, engaged and up to date board of trustees.

In repeated media coverage of the Chagall affair, inquiries to the Ministry of Canadian Heritage have been met with the comment that the operations and collections of the National Gallery are up to the gallery itself. And indeed, as a crown corporation, the NGC should operate at arm’s length.

However, the Ministry of Canadian Heritage does have something to answer for in the way it—however inadvertently—weakened the board of trustees at the gallery during a time of some crucial deaccession decisions.

The board of trustees of the National Gallery of Canada is given, in the gallery’s dispositions policy, final sign-off on deaccession decisions. It is also supposed to make these decisions on the basis of recommendations from the board’s own Acquisitions Committee.

These are sensible accountability policies and measures. Any public gallery administration in the world needs checks and balances, and this is one of them that is quite common.

It is also sensible that the trustees of our national museums be appointed, as per the federal Museums Act, by the Minister of Canadian Heritage, with the approval of the Governor in Council. This ensures that the board of trustees, which by law “is responsible for the fulfillment of the purposes and the management of the business, activities and affairs of the museum” consists of publicly accountable appointees rather than simply friends of gallery staff.

But these accountability measures only work properly when the board of trustees has its full complement of 11 term-correct members—and when its Acquisitions Committee has its own full complement of 6 term-correct trustee members. It is also worth noting that under the federal Museums Act that “as far as possible,” the terms of not more than 4 trustees are supposed to end in any one year—although under the act, trustees are permitted to stay on beyond their terms, where needed or desired, until successors are appointed.

So: At the beginning of 2017, the gallery had 10 members on its board of trustees. So far, so good. But the NGC 2016–17 Annual Report clearly shows that 6 of those trustees had terms due to expire in 2017, and 3 more of them had terms that were supposed to end in 2016. That means 90% of the board was due—or overdue—to turn over in 2017.

Now, some trustees, as per the Museums Act, did stay on past the end of their terms through 2017, waiting for replacements to be named. But at least two members did drop off in early 2017 as planned. That means that for much of 2017—including December 4, 2017, when the Globe contends the board of trustees vote on the Chagall deaccession was made—the board of trustees had, often, no more than 8 members. What’s more, at least 3 of those members were supposed to have had their terms end in 2016, and an additional 4 of them did have their terms due to expire in 2017. And during that time, there was at least one trustee vacancy on the Acquisitions Committee—possibly more.

This means that while the federal government was within its legal limits in terms of board appointments at the National Gallery, it was only just within those legal limits.

And the result, in 2017, was a National Gallery of Canada board of trustees and Acquisitions Committee that, it can only be assumed—even with all best trustee intentions—was both burnt out and under-resourced when it came to making key decisions around a major deaccession, or anything else, for that matter.

The good news, for now, is that two new board of trustee members were appointed December 14, and two more on April 1, with three more to come on June 1.

But it is very telling that it is only after some of these new board members were appointed, and the board membership again brought up to 10 members, that Wednesday night’s substantial, if “heated,” discussion of the Chagall deaccession on the board level reportedly happened.

Basically, by June 2018, roughly 70% of the National Gallery of Canada board will be new members who had nothing to do with the December 2017 deaccession decision in the first place. The reason board turnover guidelines actually exist in the Museums Act is to enhance accountability by preventing this kind of scenario—too bad those guidelines were not adhered to.

2. The National Gallery of Canada needs to reverse past staffing cuts and better resource a more complete communications and public engagement team.

In 2010, the CBC reports, “the National Gallery of Canada laid off 18 people and eliminated a total of 27 positions as part of a major restructuring.” The following year, in 2011, the CBC also reported that five curators were being let go. And in 2013, Canadian Art reported that 29 positions at the gallery had been eliminated.

Now, the National Gallery of Canada has shown, since those 2010 and 2011 and 2013 cuts, that it can indeed program exhibitions and make many kinds of collections and deaccessions decisions under current staffing structures.

But what has become clear over the course of the Chagall affair is the extent of what the National Gallery of Canada cannot do under current staffing structures, such as (a) make effective public engagement plans and strategies, from public stakeholder consultation through to rollout of public communications; (b) update its collections website in a timely fashion; and (c) consider the public (and not only artworks in the collection) as part of the institutional fabric.

And public communication and engagement is especially important in regards to deaccessions; the Canadian Museums Association Deaccessioning Guidelines recommend that in any such endeavour consider consulting stakeholders, including members of the public, as well as an anticipating public reaction and developing a communications strategy to be transparent with the public.

While considering the public, rather than only the gallery’s collection, may be anathema to a centuries-old international tradition of curating that is based in connaisseurship and protecting works of art from the elements, it is vital to note that one of the six values listed under the National Gallery of Canada’s mission statement is “Accessibility: Programs are developed with the public in mind – not only visitors to the Gallery, but all Canadians.”

It is also vital to note that the Museums Act itself states that the purposes of the National Gallery of Canada include the need “to further knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of art in general among all Canadians”—and not just in respect to objects in the collection.

So if existing, post-multi-layoff curators and staff of the gallery do not have the training nor the bandwidth to create programs “with the public in mind – not only visitors to the Gallery, but all Canadians,” nor “to further knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of art in general among all Canadians,” as indicated above, then the gallery needs to start creating positions for—and then actually hiring—sufficient staff to achieve these mandated goals.

This hiring of sufficient communications and engagement staff at the National Gallery of Canada could take many forms. Some art galleries in Canada, like the Art Gallery of Ontario, have multiple media relations staff, rather than only one like the National Gallery of Canada does. Some museums in Canada, like the Royal Ontario Museum, are hiring directors of engagement to help oversee various strategies of interacting with the public.

Granted, according to the most recent National Gallery of Canada annual report, the gallery already does have a chief of education and public programs, as well as a chief information and technology officer, a chief of marketing and new media, a chief of exhibitions and loans programs and a chief of visitor services.

But part of what is probably lacking is, first, someone who can link all these perspectives together in a strategic way “to further knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of art in general among all Canadians,” and second, resourcing of sufficient support staff to make those programs actually happen.

Whatever form the expansion of communications and public engagement staffing resources takes at the National Gallery of Canada, it needs to happen urgently. The 2011 cuts at the gallery were rationalized, according to the NGC, by the need to eliminate a $400,000 structural deficit. Given that the annual operating budget of the gallery in 2016–2017 was in the range of $60 million, finding the $400,000 (or even a bit more) to fund public engagement and transparency staff should not be considered an impossible endeavour.

3. The National Gallery of Canada Disposition Policy has to become more specific in terms of timelines for communicating deaccessions information to the public.

Though the National Gallery of Canada disposition policy indicates that “attention will be given to transparency throughout the process,” its policy needs to be strengthened with indications of how that transparency will actually play out in regards to the public.

The only indications of public communication guidelines in the eight-page dispositions policy document is this: “De-accessioned works will be listed in the relevant Annual Report, with the method of disposal and outcome noted. In addition, this information will be posted on the Gallery’s public website.”

What needs to be added to the policy document is a timeline for when deaccessions information will be posted to the gallery’s website. Is it one week after the board of trustees decides to deaccession? Two weeks? Two months? Six months?

Without a deadline for posting deaccessions notices to the NGC website, the discovery of this public-interest information is left to—as we discovered with the Chagall affair—auction-house press releases, deep-dive Freedom of Information requests, and intensive on-the-ground reporting. (While all these things are fine and good, they are far from what is required in situations that are truly “transparent.”)

Also needing to be added to the policy document: the nature of where deaccessions information will be available on the National Gallery of Canada website. The current policy guidelines basically give free rein for the information to be buried on some obscure page or link.

If some museum directors or staff currently think that clear posting of deaccessions information is impossible or inappropriate, they may want to take a look at the Newfields/Indianapolis Museum of Art website. That museum—with a budget of roughly $43 million CAD, even less than that of the NGC operating at $60 million CAD—has a fully searchable deaccessions database that can be sorted by deaccession date, artist/maker, title and more.

4. The role, responsibility and power of advisors to the National Gallery of Canada’s Acquisitions Committee needs to be made clearer.

Earlier this month, in trying to explain to the media why the National Gallery of Canada decided to deaccession Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel, NGC CEO Marc Mayer pointed, in part, to the opinion of the art historians who act as board-appointed advisors to the gallery’s Acquisitions Committee.

There were “people with PhDs in art history who are part of the process of deciding this,” Mayer told the CBC. Some of those PhDs were gallery curators, while others were advisors to the Acquisitions Committee.

While no one would likely dispute the PhD credentials of the five art historians currently listed as advisors to the Acquisitions Committee, what is less clear is what role and power those advisors have—particularly in conditions where the Acquisitions Committee is down a trustee member or two, or where advisors outnumber Acquisitions Committee trustee members, or where the committee has members whose terms were supposed to expire more than a year ago.

The National Gallery of Canada code of conduct states that advisors are, in general, governed by that code, just like staff, members of the board of Trustees and gallery volunteers. This code, among other things, states “individuals [including Advisors] shall exclude themselves from any discussion or votes when they are or may appear to be in a conflict of interest position with the Gallery.”

But while conflict of interest guidelines are clear for advisors, little else is—at least in publicly available policy and writings.

The Museums Act, for instance, only mentions advisors once in passing, without much detail—even though it does list in detail guidelines around board of trustee duties and trustee appointments at national museums. Here is the line in the Museums Act addressing advisors: “Each museum may engage such officers, employees and agents and such technical and professional advisers as it considers necessary for the proper conduct of its activities and may fix the terms and conditions of their engagement.”

Similarly, the National Gallery of Canada website lists in detail the key functions of the board of trustees—among them strategic planning, monitoring and reporting on the gallery’s performance, and risk management. It lists extensive biographies for most of its board of trustee members. But when it comes to members of the Acquisitions Committee advisors, no clear duties, responsibilities or biographies are listed.

Finally, it must be noted that while the National Gallery of Canada board of trustees has six committees—including Executive, Audit and Finance, Governance and Nominating, Human Resources and Governance and Advancement—the Acquisitions Committee is the only one for which outside advisors are listed as being retained. This suggests that—structurally speaking—outside advisors have an impact in particular on deaccession and acquisition decisions in a manner that no advisor is permitted to impact other important aspects of gallery functioning.

This is not to say that the National Gallery of Canada Acquisitions Committee should get rid of advisors—it likely very much needs them. But what is missing is (a) public clarity surrounding the responsibility and power of these advisors as well as (b) any requirement to consult, where relevant, with stakeholders (including publics and visitors) beyond that core group of advisors when necessary.

5. The workings of the often opaque Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board—which reports to the Ministry of Canadian Heritage—also needs to become more clear.

In a column posted in recent weeks to Galleries West, artist and curator Jeffrey Spalding asked a salient question in regards to recent events: “What is the role of the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board in both parts of [the Chagall/David sales] transaction?”

(Never heard of CPERB? You are not alone. It’s “an independent administrative tribunal that determines whether cultural property is of outstanding significance and national importance with a view to protect and preserve significant examples of Canada’s artistic, historic, and scientific heritage.” It’s also described as an “independent, quasi-judicial decision-making body that reports to Parliament through the Minister of Canadian Heritage.”)

Spalding wrote, “It’s my understanding that before an export permit is issued to allow an important work to leave Canada for sale abroad, an application must be made and ruled upon by the [CPERB] board. If arguments have been successfully made to the board that a 1929 Chagall painting purchased for the National Gallery in 1956 – and a David painting long resident in Quebec – are not important to the national heritage, then I wonder what work could possibly qualify?”

iPolitics columnist Alan Freeman picked up further on the CPERB question in an April 20 column about the debacle: “As Alan Lacoursière, a Montreal art appraiser told me, anybody else trying to sell a work of “outstanding significance and national importance” like the Chagall would never get an export permit so easily. Rather, the permit would have been refused “automatically” and the dossier referred to the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board, of which Lacoursière was once a member.”

Freeman’s column continued: “The Board would then have put a freeze on any overseas sale for several months to give a chance for Canadian bidders to buy the artwork.” (In fact, CPERB has currently put a freeze on exporting certain works by Barbara Hepworth, Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso and Le Corbusier for just this purpose.) “Managing to avoid the Export Review Board was unprecedented. “It [the Chagall] took days to leave the country. I’ve never seen that before,” said Lacoursière.

Art appraiser Erica Claus—a former CPERB secretary—in a column published April 30 in the Ottawa Citizen, got even more specific: “It is still not clear how the Chagall painting was granted a permanent export permit,” Claus writes. “The procedural questions fogging up the export of cultural property might also have consequences for Canada’s reputation as a world leader in museum ethics.”

As Claus indicates, “The Canadian Cultural Property Export and Import Act (1977) normally regulates the export of cultural property that is deemed of such outstanding significance and national importance that its loss would significantly diminish the national heritage.”

Claus continues: “Fine art that has been in Canada for more than 35 years and is valued over $30,000 CAD – an amount too low and out of date with current trends in the art market – requires a cultural property export permit to leave the country.”

The waters are further muddied by a different April 30 Ottawa Citizen report which states that the CPERB board was not actually engaged in reviewing the Chagall exportation, but rather that there was a representative of an Ontario gallery who was “called upon as an ‘expert examiner’ to determine whether the Chagall painting should receive the [export] permit, which would have been issued by a Canada Border Services Agency official before the painting left the country.”

So here—no matter what happened—we have, at the import/export level, another systemic check and balance that somehow managed to fail Canadians in the case of the Chagall.

And once again, it seems, lack of transparency on federal government committees—and among federal government crown corporations, like the National Gallery of Canada—are a part of the wider storm of controversy and confusion.

The directive from Claus is clear: “Before this saga ends, Canadians deserve an explanation of how this work of art left the country.”