The craze over Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrors” in Toronto recently was nothing short of overwhelming. The cause for all of the excitement and controversy was complex—yet not entirely unexpected. Kusama’s exhibition provoked dialogue about the politics of the selfie and about fantastical aesthetic elements. But not much was said in the exhibition about Kusama’s experience with mental health and the psychiatric system—a point noted in the Toronto Star by Workman Arts visual arts manager Claudette Abrams. The silence around Kusama’s psychiatric history is good in some ways: namely, it helps us avoid the tired cliché that links madness with an inherently mystical creative genius. And yet, from a critical perspective, it also erases the complexities of what it means to be mad and make art.

Workman Arts has big things to say about why mental health and the arts matter so much. As one of the first and most enduring Canadian arts organizations to support the professional training and practice of artists who have received mental health services, Workman Arts is known internationally for the work that they do.

If we want to make space for mental health in the arts, we have to make space for all of the forms that it comes in.

From May 28 to 30, Workman Arts hosted the symposium #BigFeels: Creating Space for Mental Health in the Arts. Through this gathering of artists, arts organizations and mental-health professionals, the symposium created space for attendees, presenters and participants to explore the intersections of mental health and the arts. (And many peoples’ roles crossed over: in addition to being an attendee and participant, I co-facilitated one of the breakout sessions with Cassandra Myers and Twoey Gray.) The overall intentions of #BigFeels were to create positive connections in our communities through meaningful conversations, workshops, creative activities and exhibitions.

The opening night of the symposium at Artscape Youngplace was powerful. The walls featured large-format black-and-white illustrations by Workman Arts artist Ani Castillo. Born in Guadalajara, Castillo has exhibited and published work in Mexico, Canada, the US and Spain. With captivating images and evocative phrases—including a drawing of a woman in a shirt emblazoned with the words “I wanna fight this fight”—Castillo explores issues of gender, mental health and immigration through her work.

It quickly became clear that this was not just a symposium about art, but one that turned to art as a way of making meaning. Whether through commanding performances by the Bruised Years Choir, the compelling photography exhibition “Mindset” (part of the Contact Photography Festival), or the creative efforts of community activation, #BigFeels put the links between madness and art at centre stage.

#BigFeels keynote speaker Syrus Marcus Ware (right). Photo: Julie Riemersma.

Michael Prosserman (AKA Bboy Piecez), founder of Unity Charity, presenting the Building a Culture of Positive Workplace Mental Health breakout session at #BigFeels. Photo: Julie Riemersma.

Artists Sean Patenaude, Mirna Chacin and Apanaki Temitayo Minerve, panelists for the Artists Navigating Mental Health breakout session at #BigFeels. Panel moderated by Sean Lee (far right). Photo: Julie Riemersma.

Day three of the #BigFeels symposium started with Community Resource Sharing Stations and community arts activities facilitated by artist Jacquie Comrie. Photo: Julie Riemersma.

Centring Indigenous, Black and People of Colour Perspectives

It is increasingly common to begin public gatherings with an official acknowledgement of Indigenous land and territories. These efforts are seen as one small step in processes of reconciliation. But this process went further at #BigFeels, as respected Métis Elder Little Brown Bear played a central role in the proceedings of the symposium. He was a workshop facilitator and also devoted time to one-on-one conversations with symposium attendees.

In one conversation, Elder Little Brown Bear and symposium producer Parul Pandya talked about re-Indigenizing as an effort to decentre the role of the white settler while allowing Indigenous perspectives, values and knowledges to reclaim space and place. In conversation with Little Brown Bear myself, I heard him talk about the importance of seeing madness as a gift; about making room for conversations about trauma; about the role of blood memory (that is, the way that experiences of trauma and violence can pass through generations); and about the view that medicines of the earth are powerful and alive.

I perceived a link between the Elder’s words and the ones shared by keynote speaker Syrus Marcus Ware. Boldly opening his speech by proclaiming “I have BIG feelings!” Ware shared a personal story—a style he explained was unusual for him. Ware outlined his own experiences of madness and the psychiatric institution, and how that has been deeply informed by the politics of being Black and mad in a world that sees Black mad bodies as fungible or disposable.

Ware encouraged attendees to see art as a way to disrupt and unsettle the colonial view that mad Indigenous, Black and People of Colour bodies are replaceable. Instead, he reminded us that art practices, intertwined with activist efforts, create space for collective love and rage. In this way, we were urged to centre the creations and perspectives of Indigenous, Black and People of Colour in our engagement with art and madness.

There’s More Than One Way to Talk About Mental Health

Language is powerful, political and should be used with purpose. And #BigFeels (which moved on to Artscape Wychwood Barns in later days) was remarkable in showcasing a range of ways that people identify themselves and their experiences through language. At the symposium, artists, community members and organizations opened up space for complex ways of defining and naming madness. Here are a few examples of those terms and why they matter:

Mental well…th and Mental Well-being

Starting off the symposium, Phyllis Novak of Sketch led us through a community weaving activity. Reflecting on conversations she has engaged in with Indigenous youth, Novak invited us to consider how we might step outside of the mental health industries in order to use the framework of mental well…th. This term linked, for me, with Elder Little Brown Bear’s positioning of mental well-being as a spiritual, personal and political journey which makes space for intergenerational trauma and Indigenous ways of healing.

It is important to have spaces that make room for our madness without necessitating a curative approach.

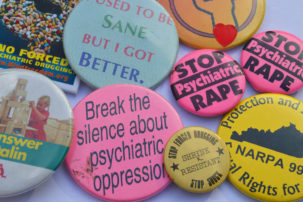

Mad Artists

Mad is a term used to make space for varied experiences of psychological and emotional difference. Like queer, it is a political taking back of language that has historically been used in derogatory ways. Connecting to local, national and international mad movement–organizing, mad artists offer unique aesthetic and conceptual elements to our social justice efforts.

Outsider Art

The history of outsider art is fraught with issues of the romanticization and fetishization of mad artistry. And yet, Apanaki Temitayo Minerve, an artist born in Toronto and raised in Trinidad, and who lives with experiences of mental health, explained in one of the artist panels that identifying as an Outsider Artist is a way, for her, of reclaiming identity and positioning her intersecting locations at the core of her art.

The use of all these phrases at #BigFeels showed that discussions about terminology are much more than technical. As an artist-activist-academic who identifies as a queer, mad, cis-gender woman, I myself felt uncomfortable with some of the terminology used—but I also feel its importance, and the importance of freedom of choice in this respect. After all, if we want to make space for mental health in the arts, we have to make space for all of the forms that it comes in—and not just the ones that make the most sense to our respective worldviews.

Going Beyond Inclusion

We gathered at #BigFeels because of a shared commitment to creating space for mental health in the arts. However, here is where I want to pause and consider how madness, as an experience and a way of existing in this world, can short-circuit inclusion strategies in productive ways. Instead, using a framework of Mad Futurities—and acknowledging that futurity is deeply rooted in the creative and cultural knowledge of Indigenous, Black and People of Colour, as well as in mad scholarship—was suggested as a way forward. Collectively, we came up with these key points:

Mentors Matter

Many of the artists at the symposium talked about how important mentors have been in their development. Mad artists need mentors in order to develop the political, aesthetic, conceptual and technical elements of our art practices.

Self-Care Is Complex

Constantly encouraged to “take care of ourselves,” many of us have become pessimists of self-care culture. Instead, we want you to consider the multitude of structural issues that affect our overall well-being and quality of life. Stop individualizing the problem.

Not All Help Is Needed

A lot of community and mental health organizations are interested in artistic approaches. This is important and meaningful. And it is just as important to remember that not all help is needed. Deaf Arts, Disability Arts and Mad Arts help us to remember that it is important to have spaces that make room for our madness without necessitating a curative approach.

Art Doesn’t Always Have to Heal the Mad Artist

Instead of coming up with simple (i.e., uncomplicated) solutions to questions of “How to incorporate mental health into the arts?” the strength of this symposium lay in its multiplicity of perspective. Through our unapologetically #BigFeels, we turn to art as a way to provoke and stimulate social change.

Making the Future By Making Mad Art

A few weeks after the symposium, I now find myself reflecting on the role of mad artists in our contemporary arts movements. As an artist-activist-academic the presence of community mental health organizations (or arts organizations that focus on mental health programming) felt overwhelming at this event. I wonder about how these organizations take hold of, shape, control and respond to the conversations about mad art.

Mad artists interrupt and disrupt current art spaces, and instead create a better future informed by a politics of justice.

What often gets overlooked in the benevolent intentions of community organizations is that there is a long history of using art practices to chart, diagnose and treat mental patients. These histories have informed the development of art programs which in varying degrees continue to contain, control and manage mad people. As many mad artists before me have pointed out, community arts organizations often overlook their own systemic power, which results in the disempowerment of mad artists in their own artistic and cultural movements.

Two years ago, in a report on the Cripping the Arts conference, I wrote about the contemporary Deaf, Disability and Mad Arts cultural movements and contextualized their rich histories of organizing. As a self-identified queer, mad, cis-gender woman, I don’t actually want to “make space” for mental health in the arts; being inclusive of mad art largely sanitizes its very purpose. Such sanitizing can be seen in the highlighting of mad art that upholds hegemonic views and values regarding mad experiences—centering art that only reinforces inspirational stories of “recovery” or harrowing tales of “descent” into madness. Seldom are the folks involved in Deaf, Disability and Mad arts—artists whose work is informed by the politics of Deaf, Disability and Mad movements—positioned as the experts in this field.

As the work of Kusama shows us, the power and beauty of madness is limitless. So I urge us to centre the work of mad artists—and in particular those who are rooted in the revolutionary movements of Deaf, Disability and Mad Arts. While at times unintelligible within individualized biomedical views of madness and distress (after all, the mad movement is not known for valuing “sense”; it disrupts the rational logic that psychiatry and related fields have used), these movements are decidedly political and inherently collective. They push back against folks who think these conversations—in art and elsewhere—should begin and end with individual-based healing.

Together, we make art as a way to love, grieve, protest, rage and make change in the world around us. Mad artists, I believe, interrupt and disrupt current art spaces and instead create an entirely better future that is necessarily informed by a politics of justice.