A New Zealander and I were seated next to each other on a recent flight to Vancouver from London, chatting whenever the in-flight entertainment system failed—which was often. Departing in the early afternoon meant we were in daylight for the entire journey, with bird’s-eye views of tundra, the Canadian Shield and the Rockies. He asked me questions I would normally Google: “How many people live down there, do you reckon?”

We flew over Fort McMurray and I described YouTube videos of last year’s inferno, not knowing that a state of emergency would soon be declared in British Columbia over growing wildfires. Today, they continue to burn out of control across the province while we city dwellers, adequately removed, lounge in the summer haze with popsicles.

Karin Bubaš, Agave Garden in Green and Purple, 2017. 152.4 by 152.4 cm. Archival pigment print. Courtesy Monte Clark Gallery.

Karin Bubaš, Agave Garden in Green and Purple, 2017. 152.4 by 152.4 cm. Archival pigment print. Courtesy Monte Clark Gallery.

“Hidden Valley,” Karin Bubaš’s solo exhibition at Monte Clark Gallery, is a series of photographs taken with LomoChrome Purple and Turquoise film, presented as large-scale archival pigment prints. The colour-shifted images, each with a coordinated frame, were shot in California and depict arid landscapes dominated by kaleidoscopic cacti, cotton candy Joshua trees and other chromatically revamped desert flora.

A pair of the images reprise Bubaš’s enduring format that positions fashionable women in outdoor settings, facing away from the camera. The ongoing series, first begun in 2006, is suggestive while withholding of narrative. Impeccably dressed figures in craggy landscapes are not merely pausing on casual strolls—something eerier is at play. Due to the known dangers associated with desert passage, this feeling is further emphasized by the iterations in “Hidden Valley.” The heeled footwear and flawless fabrics conjure visions of a broken-down Cadillac, hovering shuttle or tractor beam floating just out of frame.

Karin Bubaš, Orange Air and Teal Dress, 2017. 102 by 290 cm. Archival pigment print. Courtesy Monte Clark Gallery.

Karin Bubaš, Orange Air and Teal Dress, 2017. 102 by 290 cm. Archival pigment print. Courtesy Monte Clark Gallery.

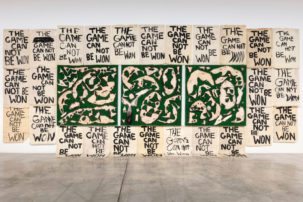

“A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug” at the Contemporary Art Gallery is equally fantastical. The show brings together approximately 450 of the artist’s versions of a largely homogenous landscape with minor variations, arranged in such a way that they seamlessly morph across the gallery walls—the calm body of water shifts from blue to grey to gold; the symmetrical flanking trees cycle through seasonal hues; and the central figure becomes a buck, or bear or moose.

Levine Flexhaug, Untitled (Mountain lake nocturne with deer, blasted tree and three birds), undated. Courtesy David and Veronica Thauberger.

Levine Flexhaug, Untitled (Mountain lake nocturne with deer, blasted tree and three birds), undated. Courtesy David and Veronica Thauberger.

Flexhaug sold thousands of these formulaic compositions at various sites across Western Canada from the late 1930s through to the early 1960s, and they’ve since turned up in charity shops and garage sales, increasingly scooped up by obsessive collectors. The near uniformity that makes each singular work tempting to dismiss also inspires awe when the group is viewed en masse. Flexhaug’s commitment to the same level shorelines and snow-covered mountain peaks is impressive. The idyllic scenes seem at odds with the mental fortitude it would have taken to produce them for so long—comparable to 25 years of eating the same meal.

An exhibition of this kind is dangerous for its potential to influence perceptions of artists and, of greater concern, of Canadian landscapes. While it’s a frustrating task to articulate the values of contemporary practices to individuals who revere this kind of oeuvre, it’s more troubling that paintings like Flexhaug’s represent, as the gallery handout suggests, “a Western icon, a silent unspoiled Eden,” which has become inappropriate for our time. This imagery should be indulged only if accompanied by the acknowledgement of the burning trees, the warming oceans and the arctic ice melt.

Maureen Gruben’s solo exhibition “UNGALAQ (When Stakes Come Loose)” at grunt gallery offers works that emphatically address the ecological and cultural effects of global warming. Guest curated by Kyra Kordoski and Tania Willard, the solo exhibition takes its title from an Inuvialuktun word for the west wind.

“When the west wind comes up, tides rise and as the earth softens, things that are staked to the ground pull loose,” says an accompanying text. The show proposes a powerful reformation, or acknowledges one already underway.

Maureen Gruben, “UNGALAQ (When Stakes Come Loose)” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Maureen Gruben, “UNGALAQ (When Stakes Come Loose)” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy grunt gallery. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Stitching My Landscape (2017) is a video-documented performance and work of land art wherein Gruben connects holes bored into an 850-foot expanse of frozen ocean with 300 metres of zigzagging broadcloth. It is tied to a memory of the artist’s brother harvesting seal gut, a similar vision of blood red on the white snow. In one gesture, the work compounds elements of immense personal and regional importance—traditional hunting, clothing and the location of the Ibyuq Pingo, near Tuktoyaktuk.

Many of the works in Gruben’s exhibition incorporate the use of fur from polar bears, animals that, in recent years, have become a living symbol of the efforts to combat human-made climate change. Message (2015) is a stretch of black interlace adorned with a long strip of woven, red cotton thread. It secures tufts of white guard hair in punctuated dashes, forming the international Morse code distress signal, SOS.

Gestation (2016) features a band of arranged tufts in a 53-inch diameter circle, resting on the gallery floor, surrounding a clutch of delicate egg-like shapes formed with sculpted underfur. The works read as invocations, appeals to assistance or protection for the animal and for the artist, emphasizing an interspecies relationship—now in jeopardy—that has existed in equilibrium for thousands of years.

Peter Gazendam, A Long Conversation (For Oona), 2017. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Peter Gazendam, A Long Conversation (For Oona), 2017. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Lastly, from carnivore to detritivore, Peter Gazendam’s A Long Conversation (For Oona) (2017) is a series of nearly 40 bronze sculptures of the species ariolimax columbianus, commonly called banana slugs, installed in and around Columbia College’s new Terminal Avenue campus and neighbouring office building. Most range in sizes of three, six, 18 or 40 inches—placed at the foot of benches, under railings, on concrete columns or stools.

The varying scale of the work is playful while prophesying an evolutionary power shift. The smaller sculptures could go unnoticed, or be mistaken for the real thing, ostensibly provoking double takes from passersby for generations to come. Their precarious placement is consistent with real-life encounters, stopping attentive boots mid-sidewalk, or falling underfoot. The lapdog-sized versions feel strangely appropriate, as though slugs could have some appeal as domesticated companions, if not for the slime.

Peter Gazendam, A Long Conversation (For Oona), 2017. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Peter Gazendam, A Long Conversation (For Oona), 2017. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Two much larger figures, measuring 10 feet in length, are centrally located in the outdoor plaza, facing each other, eyestalk to eyestalk. On the day of my visit their slumped forms are hot to the touch, baking in the afternoon heat. Ariolimax columbianus are native to Pacific rainforest floors and, like other banana slugs, they can enter a state of dormancy when the environment becomes dry. Gazendam’s creatures are poised for the long haul—perhaps until the foundations crumble, until the wet mosses, soil, trees and shrubs return.

Lucien Durey is an artist based in Vancouver. His performative works engage with collections, found objects and ephemera.

An installation view of “A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug,” at the Contemporary Art Gallery, 2017. Photo: SITE Photography.

An installation view of “A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug,” at the Contemporary Art Gallery, 2017. Photo: SITE Photography.