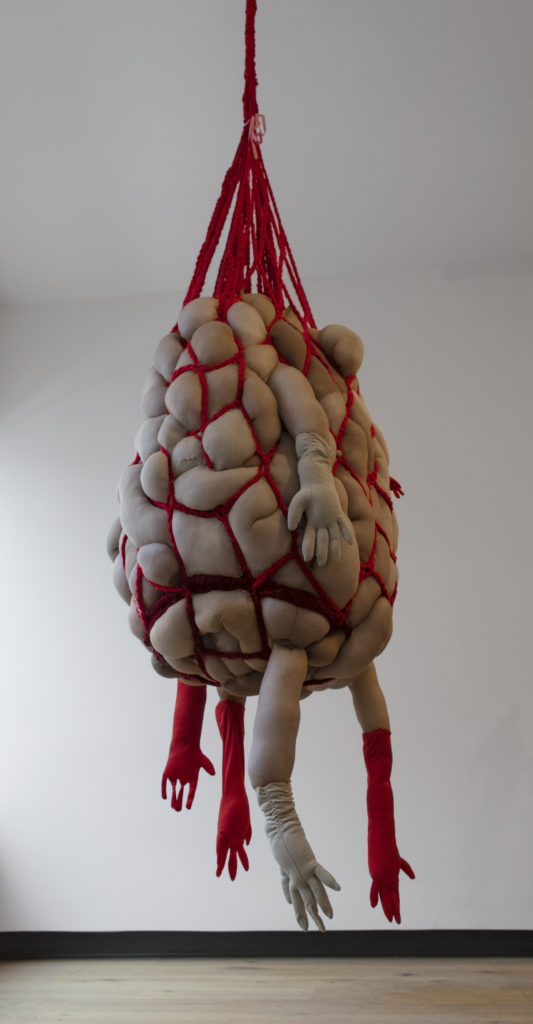

A doll by Chason Yeboah. Photo: Facebook.

A doll by Chason Yeboah. Photo: Facebook.

Chason Yeboah is a crochet artist based in Tkaronto (Toronto) and is a self-described modern doll maker. She focuses on marginalized human forms and self-love, nudity and safe-space creation. I first saw Yeboah’s work in Daniel Sterlin-Altman’s stop-motion music video Reaching the Sky (2018), set to composer Thom Gill’s arrangement of Rita MacNeil’s song “We’ll Reach the Sky Tonight” and recorded by Queer Songbook Orchestra. The video shows an enchanting story of queer support and love: three queer dolls, crocheted by Yeboah, drive down a highway alongside each other in their cars until they are separated by a fork. Each doll goes on an individual journey of queer discovery to self-love and realization. The video ends with the dolls united once again and all rising naked into the sky, shaking away the wool of the white clouds and floating into a starry night.

According to Sterlin-Altman, the video “works to break some of the clichés of LGBTQ narratives, a lot of which are depressing and focus on the anxiety of being different.” Yeboah’s dolls were a perfect match for illustrating this self-love, compassion and connection. “You exist, and just because societal standards tell you—literally tell you—that you’re not important enough to represent, just know that there are a lot of people out here like you,” Yeboah explains in an interview about her practice. Her dolls portray the vast range of bodies that divert from cultural ideals, without any insinuation that such bodies are grotesque because of their difference. Many of her dolls share features with the bodies found in feminine grotesque works: scars, fat, missing arms and legs, or pubic hair. Yet Yeboah’s dolls emphasize that these are the features of real, living people and not horrific fantasies. She says dolls allow her to reflect on the “actual things that happened in our lives that need to be represented and acknowledged.” Yeboah emphasizes that the dolls are meant for creating space for queer Black bodies like her own. She also diversifies her representations and celebrates the nuances of bodies that range from cis to trans and nonbinary: “I create these things so people can not only understand my journey, but start a narrative on their own journey.”

Doreen Garner is an artist based in Lenapehoking, homeland of the Lenape peoples (Brooklyn, New York). She uses the grotesque to examine the historical and contemporary societal disregard for the bodies of Black women. Her work reveals this contempt by extracting the audience’s overfamiliarity with the visual grotesque in the provisional gallery setting and comparing it to the very real horrors of historical medical experiments performed on Black bodies. For Purge, performed at Pioneer Works in 2017, Garner recreated the vesicovaginal-fistula repair operation that the white “father of gyaecology,” American J. Marions Sims, performed on a 17-year-old enslaved Black woman named Anarcha more than 30 times and without anesthesia from 1845 to 1849. Garner and several Black female collaborators performed the gruesome surgery on a silicon cast of Sims’s body.

Installation view of Kasie Campbell and Ginette Lund’s “Matrilineal Threads,” 2019. Courtesy The New Gallery, Mohkinstsis (Calgary).

Installation view of Kasie Campbell and Ginette Lund’s “Matrilineal Threads,” 2019. Courtesy The New Gallery, Mohkinstsis (Calgary).

A doll by Chason Yeboah. Photo: Facebook.

A doll by Chason Yeboah. Photo: Facebook.

Doreen Garner, from "Purge," 2017. Performance at Pioneer Works. Photo: Facebook.

Doreen Garner, from "Purge," 2017. Performance at Pioneer Works. Photo: Facebook.