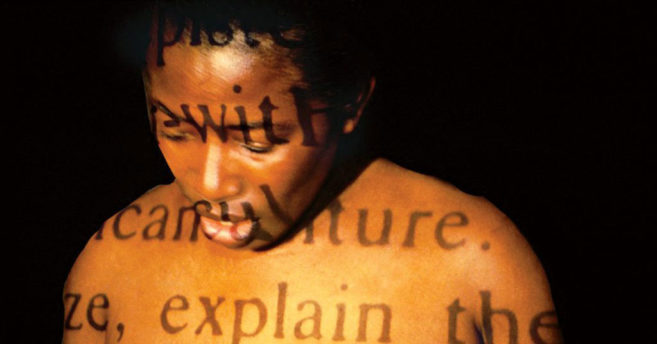

Charmaine A. Nelson

The racial biases of art criticism, the discipline of Art History, and the field of Canadian Art History made it difficult for black artists to develop and maintain a public reputation which would have allowed them to be written into the canon.… Although by no means a comprehensive or historically exhaustive work, [Towards an African Canadian Art History] seeks to contest the historical and contemporary invisibility of black Canadian artists and to critically rethink the parameters within which such artists are situated, examined, and evaluated. As such, I have strategically sought to broaden the scope of the art and visual and material cultures under examination, posing a conscious challenge to the boundaries of traditional art historical understandings of artistic value and worthiness which are often connected to economics and cultural capital as much as aesthetics.

Charmaine A. Nelson is an art history professor and was recently named the Canada Research Chair in Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art at NSCAD University. She is the editor of Towards an African Canadian Art History: Art, Memory, and Resistance (2018), from which this text is excerpted.

Katherine McKittrick

What I have learned from black studies about black geographies is that we might be joyous about the impossibility of wholly institutionalizing black knowledge. This is not about forgetting black queer, feminist, trans, or other insurgent voices, it is about knowing them differently, outside the institutional structures that crudely spatialize the black body…as only usefully conceptualized as captive and unfree and injured. This kind of conceptual captivity refuses black personhood and black livingness and obscures practices of resistance by privileging the harmed black body. Prevailing geographic systems prop up this logic: there is a reason a certain analytics of flesh (rather than humanity) is academic currency. I don’t want this anymore. I want to forget this. Or, I want to know black life differently. When I wrote Demonic Grounds the work of Sylvia Wynter allowed me to think black life differently. I want to remember this, and to remember the radical geographic work of black studies, where the fantastic nowhere of black life allows us to puzzle out new and unexpected—and undisciplined and unacceptable—modes of being human.

Katherine McKittrick is a professor in gender studies at Queen’s University. This text is adapted from her 2017 essay “Worn Out.”

Deanna Bowen

Other Places: Reflections on Media Arts in Canada was an effort to create the academic resources I needed to teach my racialized and queer students. I was specifically working to escape a predominately white-male Canadian experimental moving-image canon (i.e., Michael Snow, R. Bruce Elder, Stan Brakhage, etc.) and the white feminist constraints of the Canadian video-art canon. While these histories offer important opportunities to discuss the formal concerns of moving-image practices, they consistently introduce works by First Nations, Métis and Inuit, racialized and differently abled makers as only peripheral players. From my own experiences as a maker, I know that the scarcity presented in that canon is not how it is in real life. I engage with brilliant trans-generational makers all the time—it seemed odd that they were not written about and that their works were not given appropriate scholarly attention. This lack of care becomes a compound issue in academic scenarios where scholarly texts are a very necessary component of any effort to justify non-white-male creative artistic practice. These rigidly biased environments prioritize empirical data as accumulated evidence of worthiness.

Deanna Bowen is a filmmaker, artist and editor of Other Places: Reflections on Media Arts in Canada (2019). She is Assistant Professor of Intersectional Feminist and Decolonial 2D and 4D Image-Making Practices at Concordia University.

Rinaldo Walcott

The work I do within institutions is conditioned by a political understanding that Black struggle does not just occur on the street but in places of power. We call those places institutions, and those institutions activate modes of power that impact the conditions of Black culture and Black life. For me it is therefore crucial that the institution is understood as a site of struggle and potential transformation. Thus my participation is a conscious effort to work toward making those institutions a place where Blackness can take up space and residence.

I don’t think of my relation to the institution as one of survival. I think of it as an antagonistic relation. My engagement with the institution is fundamentally one of a political practice, and the institution is, for me, a terrain of struggle. Therefore my survival and life are constitutive of the political struggle in the first instance. Survival then is for me an inherent and necessary element of Black life and living.

Rinaldo Walcott is a cultural theorist and writer. He is a professor at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall

I am African American and grew up in the United States. From the ’70s to the ’90s, I was raised with a strong understanding of the multiple traditions of Black art and design around me, and around the world. As a kid, I took Saturday art classes at Indianapolis’s Herron School of Art and Design, and my Aunt Jill would always take us to museums to see Black artists. I was steeped in the aesthetics of Blaxploitation movies and the Black Panther movement, Afrofuturist funk album covers and, later, hip hop and rap music videos.

I am deeply interested in establishing Black self-sustaining networks and infrastructures that can build up and mentor Black artists and designers in Canada. The Entrepreneurship part of our Black Youth Design Initiative at OCAD focuses on this in design, with placements and hopefully a design incubator. I am co-organizing, with a group that includes Cheryl Blackman at the City of Toronto, networks to support emerging Black arts professionals. Our aim is to provide safe training grounds for Black artists to flourish, despite the de facto exclusion of Black artists from the most prominent art institutions in Canada. If we can make this happen, our young Black talent can flourish here and not have to go to the United States or abroad for recognition and support.

Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall is a design anthropologist and researcher. She is dean of the Faculty of Design at OCAD University.

Afua Cooper

My first introduction to art and Blackness within an academic institution happened when I was a teenager in the mid-to-late 1970s in Kingston, Jamaica. Our high school took us to art shows and poetry readings at the University of the West Indies and the National Library of Jamaica. I was introduced to Black people as painters, curators, poets, dancers and writers. It made me feel proud and grounded. I was most fortunate to grow up in a society where one’s humanity was not questioned. Here, in Canada, white people struggle to accept Black people as full-fledged humans and creators, while at the same time stealing our art creation.

I built on my knowledge of global Blackness to write, research, perform and curate different aspects of the national and global Black Diaspora. For example, I researched, curated and designed the photo exhibition “Black Communities in British Columbia: 1858–2008” at Simon Fraser University, and I lead the investigations on Dalhousie University and its links to slavery and race.

What I now find interesting in Black Canadian art is the way artists like Bushra Junaid, David Woods and Justin Augustine are using mixed media and Black history to tell a complex story of Black Canada and its links to the global African Diaspora. I think these three artists are showing what is possible for Black Canadian art.

Afua Cooper is a transdisciplinary scholar and poet and professor at Dalhousie University, where she developed and introduced the Black studies minor.