It is 1997 and I am in a high school art history class on the North Shore, near Auckland, New Zealand. My older, white, lesbian teacher introduces us to contemporary Māori artist Robyn Kahukiwa. By this time I had been living in New Zealand for three years, almost a naturalized citizen. I felt connected to the land (it is hard not to) and the people in my daily life, New Zealanders, saw me as one of them. I was already a Kiwi.

I was attending an all-girls high school (this is common, there) where everything had a slightly feminist perspective. Kahukiwa, who is a Māori woman, was presented as one of New Zealand’s leading artists. Kahukiwa’s work is familiar to the country’s small population and uses Māori myth and symbolism to explore colonialism, womanhood, family and connection to land.

This was my introduction to intersectional feminism—yes, by an older, white, lesbian teacher—and the question of the lesson was, what makes art Māori? Is it art made by Māori people, and who is Māori after the effects of colonialism and attempted genocide? Is it art made using traditional Māori techniques—carving, tattooing, etc.? The lesson was that these questions could not be answered because the question of colonization has not yet been answered. It was the work of Robyn Kahukiwa that first forced me to examine what I am now able to articulate as the colonizer state.

In 2000 I immigrated to Toronto where I completed a Bachelor of Arts in art history at the University of Toronto, and yet it wasn’t until about 2008 that I first encountered any art works by Indigenous artists. It was Kent Monkman whose work captivated me with characters and narratives that were recognizable, familiar enough for me to stare at and explore. His use of satire and humour, juxtaposed within “pleasant” landscapes, left minimal damage to my senses. His portrayal of women, through the recurring character Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, depicts Indigenous women as sexual playthings for colonizers. Monkman has mediated my experience of all artwork by Indigenous artists since moving to Canada, until now.

Standing in an exhibition at the Art Gallery of Mississauga earlier this year, I was transported back to feelings and ideas I first encountered with Kahukiwa’s work. I was reminded that colonization did not happen in isolation. As a woman whose story begins in India, with a grandmother who was displaced by partition and who fought for that country’s independence, I carry the trauma of colonization with me.

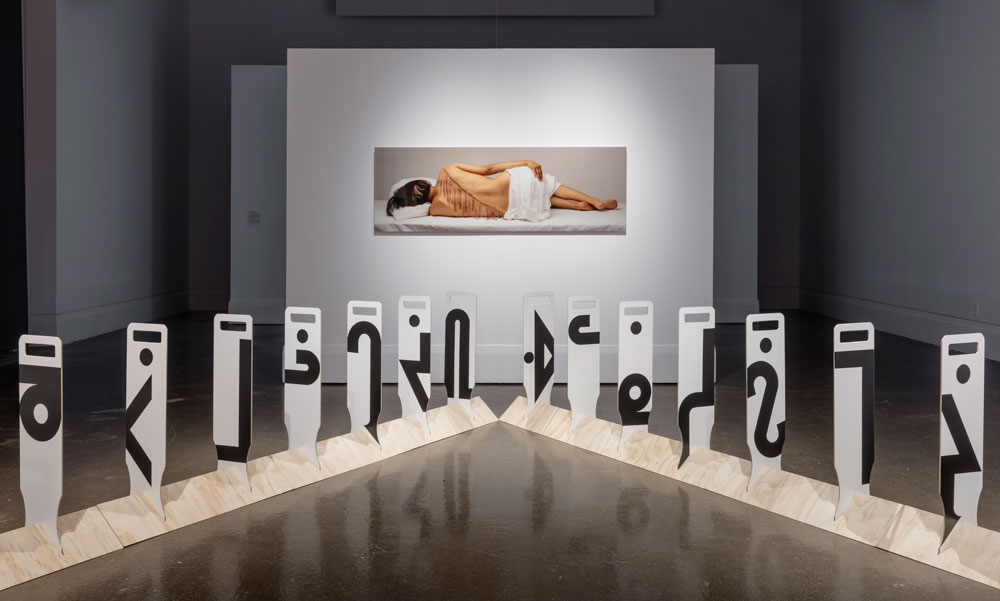

Niigaanikwewag is the Anishinaabemowin word for “leader women” and was the title of the exhibition at the AGM, which explored womanhood, sisterhood and the relationship that women have to Mother Earth. “niigaanikwewag” showed female Indigenous artists whose work has historically been left to the margins, and all of which were unknown to me. niigaanikwewag. I cannot say the word out loud. I follow each letter, but they get jumbled on my lips. As I look at the word and attempt to make sense of it, my heart gets wound up, my mind goes to mush.

It had me asking, Why do women hold the burden of healing, of creating, of storytelling? Why have I sought out this show as an answer to the question of reconciliation, a question that plagues my Twitter feed, that dominates my consumption of the news, that makes me question my relationship to Canada as a landed immigrant and naturalized citizen? Part of my motivation is that I believe the stories of women; I rely on the stories of women. But this realization further unsettles me, and so I dig deeper. The histories of New Zealand and Canada are not dissimilar, but in my opinion, New Zealand has made attempts to repaire some of the damage of colonization by beginning to restore sovereignty, and by listening to the Māori people. Some land has been returned to its original holders, the Māori. It is considered a bilingual country; my passport is written in both English and Māori, and Te Reo Māori (language) is taught through immersion like French is taught in Ontario. In fact, New Zealand’s current prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, wants to make it mandatory. I can speak at length about Aotearoa, the Māori name for the land.

But when it comes to reconciliation on these shores, Turtle Island, I am at a loss. I am able to make connections, I am aware of the history and the genocide, and yet I still feel conflicted about how I, an Indian immigrant, must come to terms with this history. And how I am a part of the future. What are the deeper and ongoing impacts of colonization on a land’s first peoples, on its settlers, on its immigrants? What does it mean for Indigenous people to be sovereign on this land rather than a part of the Canadian state? What I hear from Indigenous voices is that sovereignty is reconciliation, for the Canadian state cannot offer Indigenous people what they are due. While colonization has caused problems with the environment, housing, education, language, art, culture, fishing, hunting and the general well-being of communities, sovereignty, or self-determination, must be the answer.

A few weeks after seeing “niigaanikwewag” I was on my way to work when my attention was caught by an image on the corner of a building in downtown Toronto. The faces are familiar, as is the vernacular of the image. It is Caroline Monnet’s History shall speak for itself (2018). The idiom is obvious: a historical black-and-white image of an Indigenous woman is interwoven with a contemporary image in colour. I stop myself from analyzing its layers because perhaps that defeats the purpose, betrays the image’s beauty and power. Each morning as I ride along King Street my head turns left just in time for my eyes to swallow the installation whole. Each day I digest it a little more, allowing it to nourish my immigrant cells, regenerating the story my body carries. This image of one version of the female Indigenous story in a high-traffic location, is a witness to how the population moves and wanders through the city, how we interact with each other. It is a reminder of what the future holds, and that we need to make decisions accordingly to better the environment and the people of this land.

I spent all of 2017 consciously blocking the Canada150 “celebrations” from view. As a result I intentionally missed much of the art produced and exhibited with the last-minute funds granted to artists who are Indigenous, Black and of colour. The only show I went to see was “Every. Now. Then: Reframing Nationhood” at the AGO. I found it to be disappointing and as a whole it offered quite a limited perspective, with minimal representation of art from Indigenous artists.

But now, this year, I am seeing art by Indigenous women throughout the city. Shelley Niro’s survey exhibition at Ryerson Image Centre for CONTACT displays many decades’ worth of photo-based work that I have missed out on; that is, decades’ worth of stories that are integral to this land. For a nation which claims diversity as a strength rather than honouring its people—Indigenous and immigrant—that this work has been hard for me to access, is unsettling.

Nadia Myre’s Acts That Fade Away, also exhibited at the RIC, is a video-based reclamation of Indigenous crafts. Stolen by colonizers, instructions for beading, sewing and leather-work were recorded in 19th-century women’s magazines. Using those instructions only, Myre is filmed in silence recreating a pair of baby moccasins, a small basket, a woman’s hair bonnet and a bandolier bag Is this how crafts find their way back home to their people? Myre’s video reminds me of stories my maternal grandmother would tell me, about how the British stole pieces of art and then cut the hands and feet off carpet and silk weavers, painters, sculptors and artists in India so that they could never again create work, never pass on their skills and knowledge.

A month after seeing “niigaanikwewag” I speak with its curator, Rhéanne Chartrand. With anticipation, I listen carefully as she repeats the word, niigaanikwewag. Nii-gaa-ni-kew-wag. It is as it sounds. I feel somewhat indulgent for asking about the work and her thought process, and how she expects me, an immigrant, to wrestle with it. She has nurtured me and provided sustenance; must I also ask her to process it with me?

I am most curious to know for whom she curated this show, and I am relieved when she identifies the 16 artists in the show as her primary audience. Enacting sisterhood in an exhibition that also announces it speaks to the depth of art’s capacity to begin a process of reconciliation. She does not feel obligated to tell me this story though she does see the integral role that art plays in educating people, referring to Mississauga’s diverse immigrant population who may have a limited knowledge of Canada’s violent colonial history.

We discuss the lack of representation of female Indigenous artists and I bring the conversation to Kent Monkman. I begin to realize the limitation of the character of Miss Chief who, as a trope, is useful for his work. However, Miss Chief not only perpetuates the stereotype of a hypersexualized Indigenous woman, but in fact may co-opt the visibility of Indigenous women in the arts. With her popularity, Monkman’s Miss Chief has overshadowed these stories. Monkman’s neatly packaged narratives are palatable and made me feel comfortable that I had learned something, that I walked away feeling good about myself for understanding. But the point is not to understand—it is to question.

Reconciliation is long overdue in Canada. We have reports and studies; we have water crises, housing crises, suicide crises and many failed attempts to improve conditions. Through Indigenous art and story-telling I have become better able to frame my own place within the nation state and the dialogue around reconciliation because the experience of receiving the decolonized story is healing. In writing this essay, I have been challenged to think of sovereignty as more than a word: it is a state of self-determination that Canada needs to invest in.

The thing about the works within “niigaanikwewag” is that while they are beautiful and striking, they require no more than openness to be seen. Unlike contemporary conceptual art, which is inaccessible and requires the observer to be well versed in theory and art history in order to be legible, these stories are clear, the politics are loud, the request is simple: see, listen, repair.

niigaanikwewag. I can say it out loud, and comfortably.