“The Pavilion doesn’t even have a bathroom,” quipped curator Barbara Fischer about Venice’s Canada Pavilion in a May 2009 Globe and Mail article. That year, Fischer curated Mark Lewis, whose large-scale projections tested the limits of the small building. One could add to her list: no proper storage space, no running water, no adequately adjustable lighting, unreliable WiFi. For some of these things, Canadians have had to depend on their Neoclassical neighbours in Venice’s Giardini di Castello, Britain and Germany—whose much larger pavilions Canada’s is nestled between, and arguably dwarfed by. Occasionally, these neighbours refuse their amenities, as Britain did in 2007, when Canadians had to waddle to the French for relief.

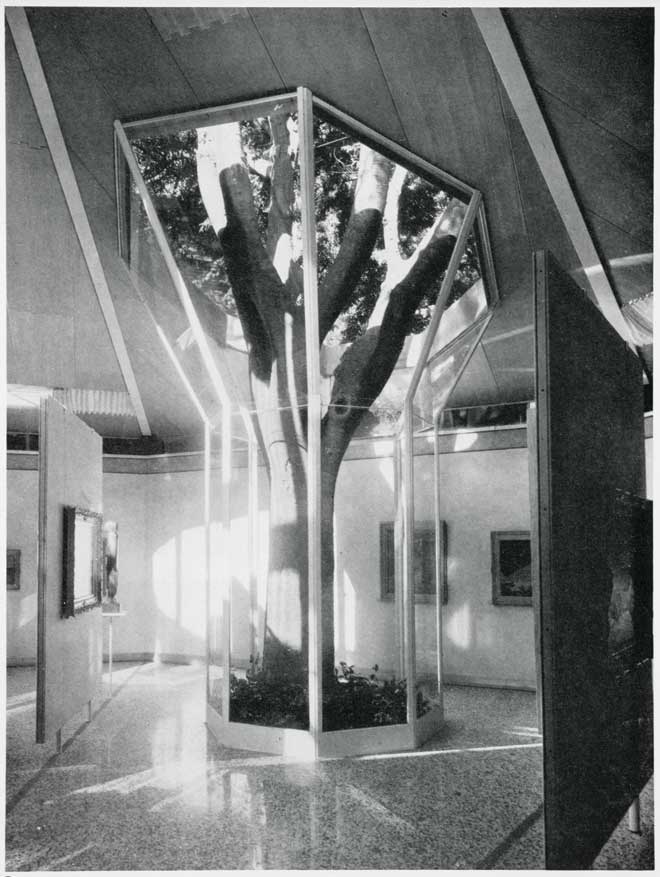

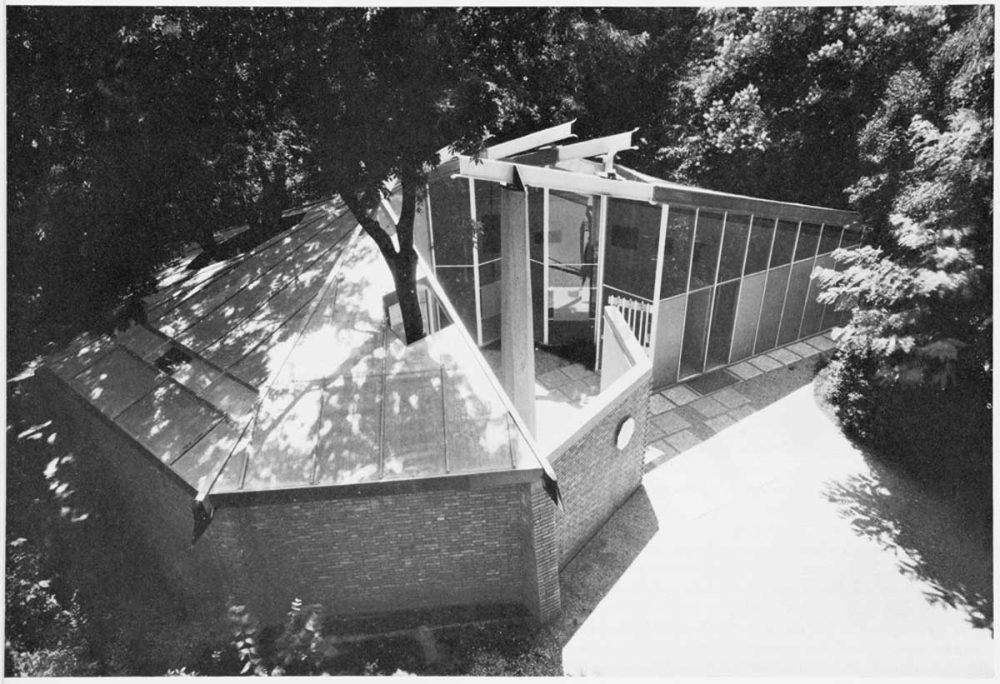

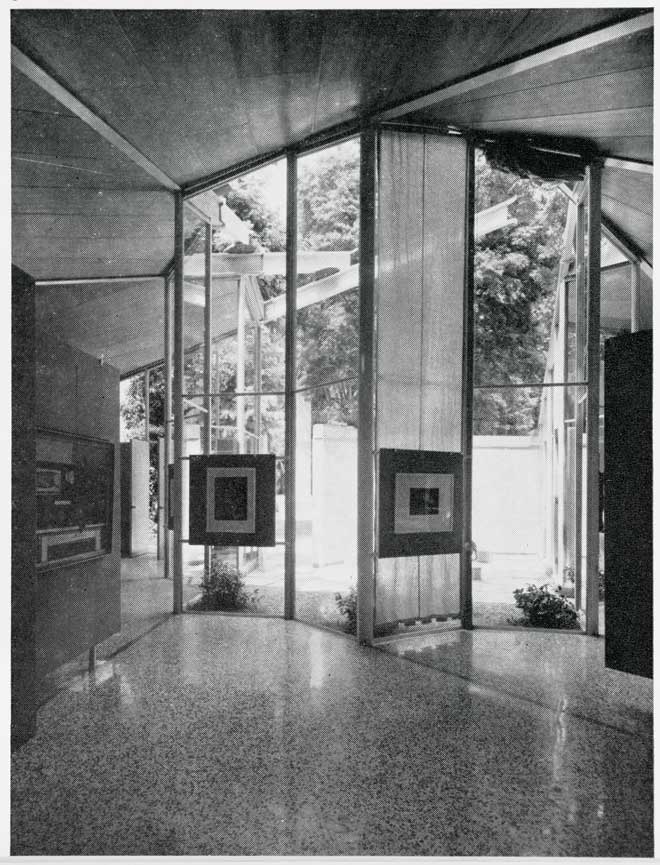

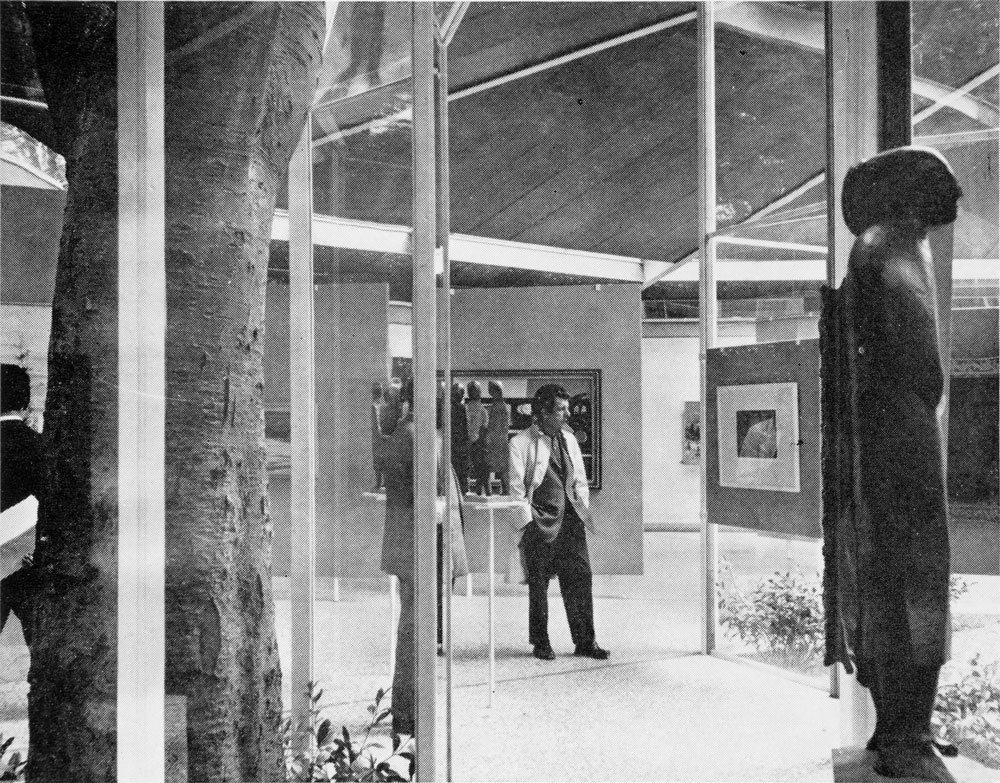

Canada’s pavilion is a series of gallery spaces arranged in a shell-like spiral. Trees, encased in glass, penetrate it. The brick, glass, wood and steel I-beam structure has a sloping roof that peaks at the spiral’s centre. Out back, there is a small plein-air courtyard. Moveable partition walls, with legs that fit into copper holes in the terrazzo floor, offer a modest, restricted ability to rearrange the space.

Built between 1954 and 1958, the Canada Pavilion had a small budget—only $25,000 CAD (the equivalent of approximately $210,000 today)—supplied by the Italians via a reserve of lire, held by Canada, and intended for use on cultural projects in Italy, in a kind of self-serving war reparation. Milanese firm BBPR was selected to design the pavilion, and the project was led by one of its eponymous partners, Enrico Peressutti, a 46-year-old who had helped make a name for BBPR before and after the Second World War as leaders, and then reformers, of Italian Modernism.

A view of the Canada Pavilion in Venice, originally published in the article “The New Pavilion in Venice” in Canadian Art Autumn 1958.

A view of the Canada Pavilion in Venice, originally published in the article “The New Pavilion in Venice” in Canadian Art Autumn 1958.

Despite an early adherence to rationalism, BBPR became embroiled in resistance, in part aesthetic, to the Mussolini regime. The war rocked BBPR’s partners: Gian Luigi Banfi was murdered in the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in 1945; Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso survived that same camp; Ernesto Nathan Rogers, a Jew, escaped to Switzerland. The three survivors reunited in Milan after the war ended, with their perspectives on design duly galvanized.

Peressutti and BBPR wanted an architecture that might forge a new type of society. They rejected monumentality, taking a more contextual approach that reflected heavily on time and space, and focused on human experience. Covering its 1958 inauguration, Canadian Art praised the small pavilion as “exceptionally fine,” with grace and elegance, originality and (how Canadian) unpretentiousness. The first show there was of paintings and sculptures: a retrospective of James Wilson Morrice, and new work by Jack Nichols, Anne Kahane and Jacques de Tonnancour.

In recent years, artists and curators have compared the pavilion to a wigwam, a birdhouse, a shed and a Parks Canada information centre. It is also, according to some of these same artists and curators, Fischer among them, not fully appropriate for the display of art. Its form is awkward, with many glass walls; its condition is increasingly decrepit, though some small renovations were undertaken in 2009. Even the Canada Council, former managers of the pavilion, have referred to it as “notoriously inhospitable to contemporary artwork and in particular to new media.” The pavilion’s new managers since 2011, the National Gallery of Canada, are beginning restoration work on the structure, slated to be finished in 2018.

A view of the Canada Pavilion in Venice, originally published in the article “The New Pavilion in Venice” in Canadian Art Autumn 1958.

A view of the Canada Pavilion in Venice, originally published in the article “The New Pavilion in Venice” in Canadian Art Autumn 1958.

Yet the pavilion’s prime location and quiet presence, as well as its place within the trajectory of Italian architecture, particularly as a relic of BBPR’s oft-forgotten impact, make it one of the Giardini’s more intriguing buildings. Artists who show here must consider and react to the space—it can never be a white cube—thus realizing Peressutti’s desire for people to ponder the space and its trees, scale, materiality and form. To experience the Canada Pavilion, either critically or with wonder, is to engage with history, context and humanism. Peressutti’s structure acknowledges nature: that of Canada, and of the pavilion’s verdant spot in the Giardini, overlooking the lagoon. In a sea of ostentation—Germany’s austere, grandiose building was famously rebuilt in 1938 on Hitler’s orders—the Canada Pavilion tells a design story that is strikingly accessible.

Curator Josée Drouin-Brisebois, who brought Steven Shearer to Venice in 2011, spent some time looking into the story of Peressutti after visiting the pavilion with Shearer, who was at the site for the first time. In Shearer’s monograph, she quotes BBPR: “From the masters we have learned not to imitate past styles,” they assert, “but in designing a new organism we strive to put it into a ‘sympathetic’ relationship with its surroundings, whether natural or man-made.” BBPR thought of Modernism as a “continuous revolution.” In Peressutti’s world, a Biennale exhibition meant paintings on walls and sculptures on plinths. His was also a world in which architecture was active, narrative and unique. Such qualities may be unsuitable to a gallery, but they define many great works of art.

This article, under the title “Our Pavilion,” originally appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Art. To get each issue of our magazine delivered straight to your mailbox before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

A view of the Canada Pavilion in Venice, originally published in the article “The New Pavilion in Venice” in Canadian Art Autumn 1958.

A view of the Canada Pavilion in Venice, originally published in the article “The New Pavilion in Venice” in Canadian Art Autumn 1958.

The Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Archival image courtesy the National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Mondadori Press.

The Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Archival image courtesy the National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Mondadori Press.

The Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Archival image courtesy the National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Mondadori Press.

The Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Archival image courtesy the National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Mondadori Press.

A view of the Canada Pavilion entrance during Shary Boyle’s installation there in 2013. The pavilion is due to be restored by sometime in 2018. Image courtesy the National Gallery of Canada.

A view of the Canada Pavilion entrance during Shary Boyle’s installation there in 2013. The pavilion is due to be restored by sometime in 2018. Image courtesy the National Gallery of Canada.

Two captions in this article were corrected on May 12, 2017. The captions erroneously dated their images as being from 1958 in the original post, when at least one of them is post-1965.

A view of the Canada Pavilion soon after its opening in the 1950s. From “The New Pavilion in Venice” in Canadian Art, Autumn 1958.

A view of the Canada Pavilion soon after its opening in the 1950s. From “The New Pavilion in Venice” in Canadian Art, Autumn 1958.