We ride cloud cover, and then the ground. Snowfields, airfields, some fluorescent imaging of the interior, some dark extraction, both wet and dry. As viewers, as spectators, I mean, of Hollow Earth (2013), a 16 mm film by New Mineral Collective that slowly drops us through the resource conditions of the circumpolar North like a plane, some eye or a drill. Like some camera—that which is both a drill and an eye—into layers of geostrata, surface mining and subterranean depths, some white, black and red. In our exemplary extractivist present, as all natural and human resources are thoroughly probed and plundered—as the earth is increasingly understood as sacrifice, both analogous to and equivalent of; as it is figured as both mother and daughter of the great patriarchal epics, newly rewritten so as to not simply sacrifice some daughter for wind and victory, but to sacrifice the wind itself—the earth is being increasingly reached into and scraped clean. How to image and imagine that, how to see it—the glittery-political-ecological apocalypse all around us—and how to stop it? Can the optical record be framed as a form of resistance? Or is it always passive in its distance? These are some of the questions that New Mineral Collective, a collaborative platform under the auspices of artists Tanya Busse and Emilija Škarnulytė, seems to ask in this and other recent films and installations. Indeed, moving images seem to ask this of us.

Recently, I wrote: “I dreamt of horns in the earth.” Then: “Tell me about the mouth. Its voids, vacuities, soft openings…. Its vessels of leak and desire and extraction and withholding. Its collective and non-collective actions.” I didn’t dream, I didn’t write, of snowfields, nor of refineries, extracted materials or shadowy industries, but why not? Fluorescent aerials or interiors, what have we touched there? What should we not have touched? What pours out of the earth? How to extract meaning, not material (even as that resource, so material, pours forth)? Watching a series of films by New Mineral Collective, these are some of the queries I began to ask myself, and which it appears the artists might have been suggesting (seeing into being, perhaps) in their films, performances, sculptures and installations created together since 2013.

New Mineral Collective’s highly aestheticized films are all surface and interior: cresting white mountains delineated against heavy white skies, soft pools of glittering salt flats, fluorescent desert boulevards, pale bodies in turquoise night pools or aquamarine seas, dark material churning through dark refineries, light-strobed factories, drill bits plunging into the earth, strange imaginings of stranger interiors. Their works are, too, subtle optical meditations and counternarratives on the acts of extraction and contamination and capitalism and, yes, all that relation and desire that happens in between.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

Thus their moving-image works visualize that which is often opaque, hidden from view, from images themselves: the extractive industries that have created a new landscape politics as well as new landscapes. See the soft pink, white and blue pools of the Dead Sea in Your Body Is A Mine (2019), its shimmering expanses of salt flats and pink cliffs, its pale shores littered with salt factories, commercial spas for tourists, political trauma and apartheid, a geo-political space of weightlessness and weighted politics, of extraction and violence and wellness. The light in the film is overpowering—it trembles. No bodies but industrial bodies in sight. “The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live,” Audre Lorde writes, famously, so lit. But what if there is no light, in some interior, and what product?

In her poem “Coal,” Lorde writes that the titular material “Is the total black, being spoken / From the earth’s inside. / There are many kinds of open.” What is open and what is closed in a world in which extraction and patriarchy and racial capitalism are the only theology and operating methodology, when plunder is the expert gesture? If making visible is itself a mode of extractivism, bringing all to light, to surface, how can images resist this, become counter to such pillage? To that end, New Mineral Collective understands its collective actions, its collective works—their studious, sometimes voluptuous images of surfaces and violable interiors, of the extractive industry that is reaping our landscapes, dropping deeply into its withholdings—as acts of counter prospecting. Coined by architect Kjerstin Uhre, counter prospecting is described as an “interpretative praxisbased method that operates on two intersecting planes: It resists dominant and already given prospects, while on a plane of anticipation it reaches beyond these in a prospective exchange towards possible alternate futures.”

In the hands, and eyes, of New Mineral Collective, this term manifests in myriad acts: acts of making as well as acts of wellness and body relations, like acupuncture, massage therapy and weightless submersion. Such “acts” suggest the recent rhetoric of self-care, writ everywhere, which is paradoxically employed by both commercial wellness industries and contemporary resistance movements as a necessary survival technique in our era of “great derangement,” per Amitav Ghosh (in his 2016 book, subtitled Climate Change and the Unthinkable). The artists of New Mineral Collective themselves write: “The act is the method and the goal is to prospect alternative forces… desire, poetry, love, passive resistance, lust, water, etc.”

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

Desire, poetry, love, passive resistance, lust, water: Are these alternative forces another series of “natural” resources to mine, to extract—but from what? What will they fuel, and to what end? Under the passive sign of these questions I watch New Mineral Collective’s film Neon Oasis (2017), in which some lust resistant to resistance, like water to oil, seemingly presses its moving images forward. The film drops us into the druggy deserts of the American West Coast—Joshua Tree National Park, Bryce Canyon National Park, the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Utah salt flats—and then moves to spa therapies and desert suburbs of unofficial, “squatted” mining plots, in a kind of collective hallucination. Its artists have written of it: “The feminine body mines pleasure and seduction within man-made environments.” Yes, but does it mine understanding, resistance? Is pleasure always passive, supplicating, or can it be counter? Another question: Does our desire mine material— pleasure, violence, banality, ideology, mineral, animal, all of their shimmering products and emotional currencies—or does it mine us? How to resist this personification, this codifying earth as a feminized body—dark, glittery and open for extraction—when industry already does it so well? “Penetration Is Our Destination,” recites the Arctic Drilling Company cheerily. How to read the earth’s surface not as a skin—forever penetrable, vulnerable, violable, gendered—but as a surface? How to pierce the violence, not the surface (not the earth)?

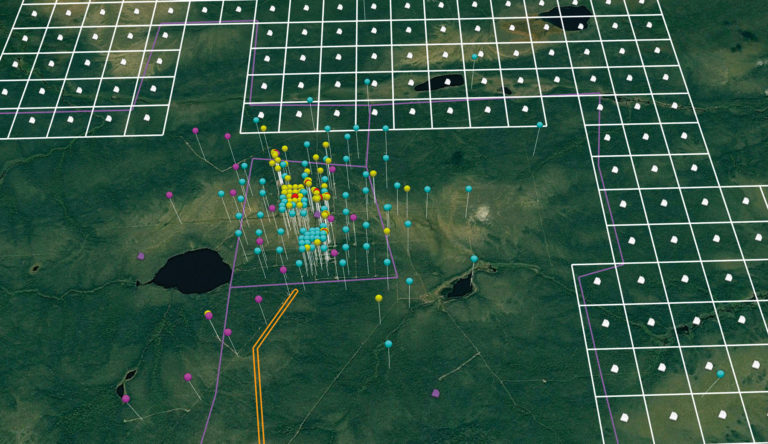

For New Mineral Collective’s most recent commission, made for the first edition of the Toronto Biennial, which opened in autumn of 2019, the artists began acquiring mineral licences—that is, prospecting licences—for Ontario, where an overwhelming number of international mining companies are headquartered. The ease of the process surprised the artists with its colonial-corporate effortlessness: They didn’t have to visit and see the land they were licensing and claiming, nor have any connection to it beyond demonstrating what resources they planned to extract from it and for what profit. They had to provide the requisite office with “standard penetration tests” to prove that they were proceeding with the geological plan they had proposed, yes. Yet their real aim is to leave these plots of lands closed, passive, unpenetrated, unwounded—nothing of “value” will be extracted from them. Well, not nothing. On the plots of land they have claimed, the artists intend to invite writers and thinkers who will be asked, in turn, to suggest proposals for acts of counter prospecting. What might the land yield besides capital, profit, violence, ruin? What other values might be yielded from other New Mineral Collective members? Desire, poetry, love, passive resistance, lust, the artists seem to recite, seem to echo, somewhere.

Alongside this ongoing project, the artists created two new works for the Toronto Biennial. First, a series of 12 glittery, striated sculptures—suggesting a group of columns or obelisks or drill bits without the edges or monster monumentality—explore the materiality and aesthetic manifestations of deep time and deeper earth. As the artists write, the “sculptures are casts of earth scars and represent a folding space and time. Absence becomes presence.” The sculptures are casts of various prospecting boreholes created from slag from around Ontario, which the artists then variously mixed with copper, silver, aluminum, zinc, steel and gold. Their design is to return the holes left by mining companies to a state not quite original—whatever that is—but to something close. “It’s about replacing what has been already taken out of the earth, or making it whole again,” they say. Understood as a geo-trauma “healing tool,” each sculpture is dedicated to a specific borehole that has been prospected already, and which has left the earth duly scarred, incalculably open. These sculptures, then, become that scar lifted from the earth, made manifest in air.

Is this what future “ownership” will consist of? Reaching into the earth, then pulling out our arm and reaching our hand up to stroke a face?

Seen in group, and in the context of an exhibition, as artworks for public viewing and consumption and trading and critical reflection—all the contemporary rituals of the contemporary art world—the sculptures also suggest a number of aesthetic analogues. Totem poles, for instance, particularly mortuary poles, which house the remains of the deceased; in this context, the remains are the perforated earth itself. But the obelisk is also suggested, from the ancient Egyptian to the Roman to more modern versions, those that dot cities like Paris, for example, crafted as they are from stone and mineral and sometimes precious metals. Manifested in such attenuated, upright form, this material takes on the cast of a body, of a series of bodies; the anthropomorphism that results might allow the viewer to approach and see such material as living, and so due the respect of all that might be hurt or mortally wounded. Maybe. But our contemporary sympathies are not always so giving, so allied with the nonhuman, with the mineral.

Another excerpt from another poem, this one by Louise Glück, her lines like lacerations in the earth: “didn’t the scar form, invisible / above the injury / terror and cold, / didn’t they just end, wasn’t the back garden / harrowed and planted— / I remember how the earth felt, red and dense.” She ends this poem, called “October,” by asking: “weren’t we necessary to the earth.” That necessary query, and the chant-like song in which it is delivered, suggests some of the same urgency of New Mineral Collective’s new moving-image work Pleasure Prospects (2019), also presented at the Toronto Biennial. A video composed of various shifting layers of subject and tone that the artists constellate and sift through (like strata of some glittery earth), Pleasure Prospects opens with some animation, some animated topos, as the artists digitally scroll through Ontario’s topographical landscapes and earthly interiors to research prospective claims as they adhere to the regulated process for acquiring mining rights. (These black-and-white animations also strangely suggest, to me, the organic and curving interiors of Ruth Asawa’s wire sculptures.)

These moving images then switch to another kind of topographic surface, another kind of dark interior: an annual mineral-mining convention, one of the largest in the world, mounted in Toronto, called PDAC: The World’s Premier Mineral Exploration and Mining Convention. That many of the convention’s booths feature animated maps and digital light-box images of pristine landscapes—the better for industrial penetration—highlights the fact that the corporate-state imagination of the interior is now a digital one, for better or, likely, worse. Language streaks the surfaces of these booths and the convention’s infrastructure: escalators laden with dark-suited men read, “Creating Long-term Value” along their flowing bannisters; inoffensive white fonts against mountain landscapes read, “Discovering Tomorrow’s Futures.” That those futures are dark, that they are a wound, that they will leave ruin, seems a mere footnote for the prospect of wealth “creation.” A different kind of creation story, and one which New Mineral Collective counters with its move into pleasure, healing, some formation of community.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Columns, casts of prospecting boreholes, rammed earth, hand-pulverized black copper slag, copper, zinc, steel, aluminum, fine gold and silver shavings and concrete, dimensions variable. Courtesy Toronto Biennial of Art. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Columns, casts of prospecting boreholes, rammed earth, hand-pulverized black copper slag, copper, zinc, steel, aluminum, fine gold and silver shavings and concrete, dimensions variable. Courtesy Toronto Biennial of Art. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

New Mineral Collective, Pleasure Prospects (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 16 minutes, 30 seconds.

Thus against these scenes come more startling, speculative ones: spas situated with modernist sculptures, coastal and industrial landscapes in which women in zebra-stripe-printed bodysuits offer each other obscure wellness routines and facials, hydro-drill therapy with synchronized swimmers, acupuncture on topographical maps and then on breathing bodies, and choreographed dance routines flourishing inside the rusted grids of light-strewn, post-industrial cities. The artists have noted that such therapies are “procedures that mine through the body.” These are the geo-trauma therapies that might—prospectively—heal the penetrative wounds of extraction. They are funny, sad, strange, impossibly weird and moving. But so is the body, the body of the earth and the bodies we often call our own. Is this what our future will look like? Is this what future “ownership” will consist of? Or is this our present? Reaching into the earth, then pulling out our arm and reaching our hand up to stroke a face? All our surfaces? To face them, finally, with attention and care? What wellness routine will heal this mess? How to redirect the penetrating attention of those men in dark suits riding their escalators to our collective dark futures and possible extinction to some other horizon, some other view of the world and what is possible within it? What aesthetics, what politics, what images can alter this fever for wound-making, this destruction for profit? Salt in the wound, ore in the ground—which is it?

New Mineral Collective’s films—which are often gifted propulsive electronic soundtracks with new-age touches and flourishes—seem to coax forth such queries and the language of inquiry itself. Indeed, the oft-posited barren “wilderness” of New Mineral Collective’s chosen landscapes, chosen subjects—the far north of the Arctic, North America, the deserts of the American West and the Middle East—are in fact teeming with industrial and military activity at both the surface and just under it: mineral prospecting, oil extraction plants and refineries, military bases, radar stations, nuclear reactors and testing sites, nuclear submarines. Such dark activity—a convergence of the neoliberal corporate state’s voracity—suggests the need for, yes, counter prospecting, some possible future counter to the apocalyptic one to which such extractivism is leading us. Desire, poetry, love, passive resistance, lust, water, the artists repeat, a litany, a montage, a collective chant by which to conjure and to, perhaps, begin.

New Mineral Collective, Your Body Is A Mine (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 6 minutes, 30 seconds.

New Mineral Collective, Your Body Is A Mine (still), 2019. Ultra HD video, 6 minutes, 30 seconds.