A few years ago, Lani Maestro won the Ottawa-based Hnatyshyn Foundation’s prestigious Visual Art Award for mid-career Canadian artists—an award that has also gone to Kent Monkman, Rebecca Belmore and Geoffrey Farmer. Yet Maestro is relatively low-profile in Canada at this point in time, even though, on May 13, her exhibition at the Philippine Pavilion at the Venice Biennale will be opening to the public.

Those who do know Maestro also know of her commitment to an ideal of practice that is, in her words, “independent”—as “critical” and “social as it is simultaneously wild and sensual.” And Lani Maestro’s talent and influence should not be underestimated—she has exhibited at the Sharjah Biennial, the Busan Biennial and the Istanbul Biennial, among other major international events, and she taught for years at Concordia University and NSCAD (also her alma mater) after arriving in Canada from the Philippines at the age of 25.

Right now, at the Venice Biennale’s Philippine Pavilion, Manila-based curator Joselina Cruz is putting Maestro’s works in dialogue with those of painter Manuel Ocampo. The pavilion, placed right in the midst of Venice’s 13th-century Arsenale, a hub of world’s longest-running international art event, also offers the potential to spark fresh dialogues near and far around Maestro’s art.

Here is one such dialogue: an email interview with the artist, completed just this week as the Biennale was holding its media and VIP previews.

The newest work in Lani Maestro’s Philippine Pavilion presentation at the Venice Biennale is meronmeron

The newest work in Lani Maestro’s Philippine Pavilion presentation at the Venice Biennale is meronmeron

(2017), a series of benches, visible in this photo, that Maestro hopes is an invitation to viewers to an invitation to “pause, to be with oneself alone, or be alone with others.” Photo: Paolo Luca. Courtesy of the Philippine Pavilion.

Leah Sandals: You told the Winnipeg Free Press in 2011 that your “work always tries to have a conversation with where it’s going” and that “it embraces and talks to its context.” How are you hoping to put your artwork in conversation with the Venice Biennale context, or the Philippine Pavilion context?

Lani Maestro: I have three works in the Philippine Pavilion. Two of them were shown in other contexts before. It was almost impossible to work with the space, as we were not allowed to touch the physical structure—i.e. walls, beams, etc. But none of us wanted to build false walls to make a clean-looking space that resembled a gallery.

The Arsenal space is quite beautiful with its “textured” history. There is this embodied history within the architectural space that already is a trace—or presence of a community, invisible as it is.

Since this is a curated exhibition of two artist’s works, I thought a lot about my work adapting to the space in relation to Manuel Ocampo’s paintings. I hoped that the conversation would be evident, while simultaneously keeping the “difference” of our particular works. Together with the curator, Joselina Cruz, we discussed these possibilities, as well as the fluidity of movement in the experience of both our works.

My proposition of meronmeron, the third piece with the benches, tries to make a bridge between both works, creating a pause, anchoring viewers within this experience, as all the national pavilions [in the Arsenale] are linked together through open portals.

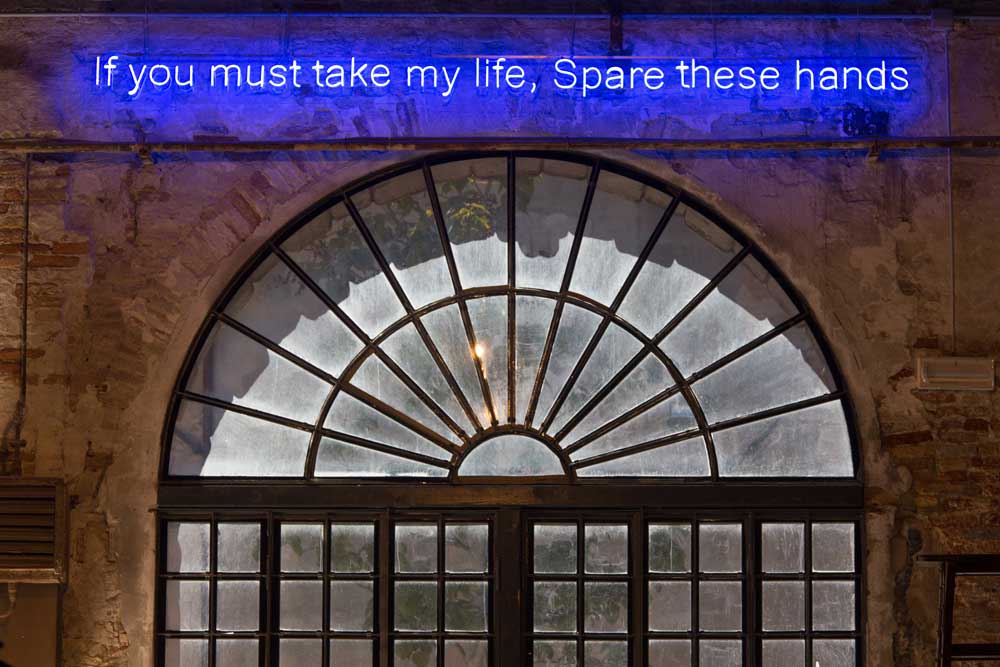

This neon work by Lani Maestro, hanging in the Venice Biennale’s Philippine Pavilion, was originally created for an exhibition at Centre A in Vancouver. Photo: Paolo Luca. Courtesy the Philippine Pavilion.

This neon work by Lani Maestro, hanging in the Venice Biennale’s Philippine Pavilion, was originally created for an exhibition at Centre A in Vancouver. Photo: Paolo Luca. Courtesy the Philippine Pavilion.

LS: I have read that one of your neon works used as an advance image for this show, No Pain Like This Body, came out of walks around Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Will this piece be in the Venice exhibition? If so, how do you hope it reads in this new locale?

LM: Yes, this installation is in the Arsenale right now. It feels like the perfect choice to accompany Manuel Ocampo’s works in this exhibition.

A few years ago, I was invited to come and see the Centre A gallery space, then on Hastings Street in Vancouver, and those words, “no pain like this body,” came to my mind. They are not my words, but those of Harold Sunny Ladoo, who wrote an acclaimed book of the same title.

I think the emotion or feeling this particular artwork evokes touches everyone. The Biennale is not an impoverished location, but perhaps a certain kind of impoverishment or homelessness also inhabits each and everyone of us.

In the weeks that we have been working, I have observed people around us—cleaning ladies, builders, painters, security guards, curators, artists—looking, watching, talking, but also making comments from afar as the installation was slowly coming together. So there is already a reverberation of some kind, even before the work has been finalized.

LS: Also, are there any works in the Venice show that come out of your walks around (or other physical experiences of) Venice? If so, how? What other new works (if any) are in the show?

LM: I mentioned the new installation meronmeron above. Perhaps the idea also arrived with the thought of an audience within a large-scale exhibition like the Biennale. It is an invitation to pause, to be with oneself alone, or be alone with others.

Another work, these hands, is a neon installation that was originally mounted to accompany a larger installation at a closed-down jewellery factory in Ardèche, the south of France. As in a lot of places, there is this industrial landscape of abandonment as a result of globalization.

Lani Maestro’s neon artwork in the Philippine Pavilion (at left) with paintings by Manuel Ocampo (at right). Photo: Paolo Luca. Courtesy of the Philippine Pavilion.

Lani Maestro’s neon artwork in the Philippine Pavilion (at left) with paintings by Manuel Ocampo (at right). Photo: Paolo Luca. Courtesy of the Philippine Pavilion.

LS: In 2012, you told Planting Rice that for young artists, you want to reinforce that “it is important to be independent and that it is possible to continue making art in a manner that is critical, social as it is simultaneously wild and sensual.” Do you still feel this way? Why or why not? How have your experiences as a teacher at Canadian art colleges and universities influenced your creative practice, or your views on creative practice?

LM: Yes, I do still feel this way. I have been making art for 40 years or so, and I have done so independently. I put a stress on “independence,” because even if one has gallery representation, it is still important to keep this sense of freedom. I accept the business side of what I do, and I would be a hypocrite to say otherwise—but as I have also said, it is important to practice a certain kind of ethic, the ethics of care.

Teaching made me “study” enormously, as I approached pedagogy as learning together with my students. But, like everything else, universities and colleges were changing rapidly during my teaching years with the introduction and advancement of technology. At some point, it bothered me that I did not hear the word “inspiration” being uttered anymore. And I also remember the time when students began to refer to art as an “industry,” and set their goals merely towards gallery representation and the like.

A visitor views Lani Maestro‘s neon work at the Venice Biennale’s preview for the Philippine Pavilion. As Maestro writes, “the Biennale is not an impoverished location, but perhaps a certain kind of impoverishment or homelessness also inhabits each and everyone of us.” Photo: via Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale Facebook page.

A visitor views Lani Maestro‘s neon work at the Venice Biennale’s preview for the Philippine Pavilion. As Maestro writes, “the Biennale is not an impoverished location, but perhaps a certain kind of impoverishment or homelessness also inhabits each and everyone of us.” Photo: via Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale Facebook page.

LS: The curator of the Philippine Pavilion, Joselina Cruz, has stated that she chose your and Manuel Ocampo’s works in order to present “a more complex imagining of the local and global as each artist re-defines political resistance within their experience of shifting localities throughout their artistic careers.” What are your perspectives on locality and political resistance right now? How to do you relate to those parts of your career and practice that have happened in Canada, as opposed to other places?

LM: You know, I am happy that you are even having this interview with me, as I am representing the Philippines at the Biennale, and not Canada. The other Filipinos are also impressed. It is a wonderful expression of Canada’s openness and progressive thinking, especially with the looming conservatism that is hovering above us at the moment.

I am Canadian and I am also Filipino. Nationalisms that are based on purist thinking easily become fascism. Categories are not that important; consciousness is. If we have consciousness, then we would be capable of careful listening and mindfulness of “difference.” We would be more present in the here and now—and that is all that counts.

This interview has been edited and condensed.