In the middle of curator Christine Macel’s “Viva Arte Viva” exhibition at the Venice Biennale, Montreal artist Hajra Waheed has built another world. Not through elaborate, immersive sets, but by using small fragments and glimpses into a life remembered and documented.

In Waheed’s space, a small room bordered by the work of American painter McArthur Binion and Syrian painter Marwan, the artist has brought together five bodies of work that range from collaged photographs and glass slides to gouache paintings on Masonite mounted on brass and wood. But the most remarkable element of her presentation is this: a series of 38 oil-on-tin paintings that mark an important return for Waheed to painting, which she hasn’t dealt with much since her university studies.

“I studied painting in art school, and yet it was over a decade or more before I could come back to it again,” said Waheed. “I went the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and graduated with a BFA degree in the advanced painting [studio], and I think that, having studied painting in a particular way, it was almost as if my body refused it. I needed to get really close to my practice to finally let painting back in and to allow myself to be with painting outside of what I had learned—to shed that institutional layer, if that is even possible.”

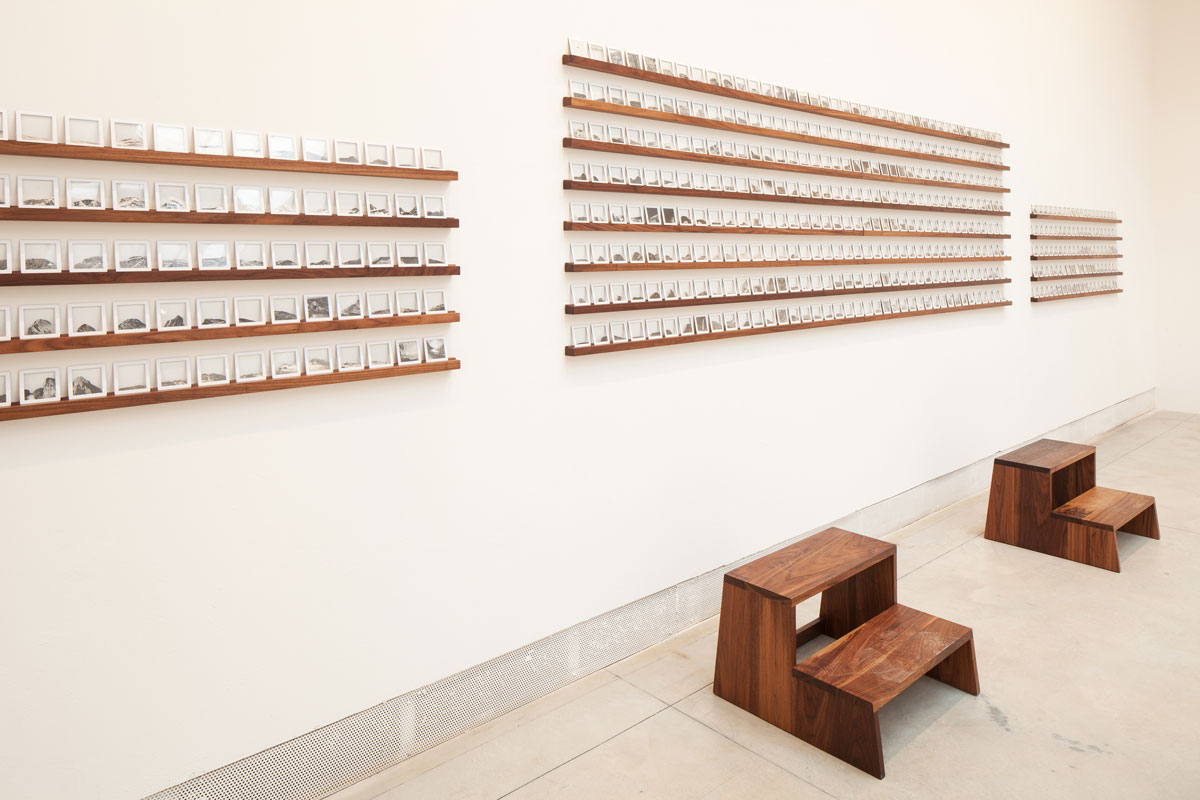

Oil-on-tin paintings from Hajra Waheed’s Avow 1-38 (2017) are positioned on wooden shelves at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

Oil-on-tin paintings from Hajra Waheed’s Avow 1-38 (2017) are positioned on wooden shelves at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

It would seem so. Waheed’s paintings possess a melancholy beauty. The works on tin, titled Avow 1-38, register like photographic snapshots: the scene of a night sky, an ocean meeting sand, a pair of outstretched palms. The subject matter captured in these paintings, like the photographic collages and gouache paintings on view, suggest a journey: the landscapes presented are the destinations encountered, the views of the sky record an attempt to track location. Each celestial or geographic painting is twofold—it could offer some sort of tracking information, and it is undeniably beautiful.

The atmosphere of these works reminds me of scenes in Emily St John Mandel’s novel Station Eleven, set in North America after a vast epidemic has killed almost the entire population, and life becomes entirely migratory and survival-based. “What was lost in the collapse: almost everything, almost everyone,” writes St John Mandel, “but there is still such beauty.”

The five bodies of work shown in Venice are all a part of Sea Change, a large, lifelong project to which Waheed continually returns. She has described the project as a kind of visual novel which follows nine protagonists over nine chapters, tracing journeys that they make, journeys all precipitated by catastrophe.

A view of some objects from Hajra Waheed’s A Short Film series, comprised of negative glass slides, collaged photographs and wood shelves, installed at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

A view of some objects from Hajra Waheed’s A Short Film series, comprised of negative glass slides, collaged photographs and wood shelves, installed at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

The work on view in Venice is but a sliver of the Sea Change project. Naturally, there is no clear explanation offered in the exhibition—no narrative resolution—although Avow 1-38 offers the most representational portion of Sea Change thus far. But Waheed allows viewers to attempt a search: there are stools within the space, and throughout the preview visitors scrambled up them to glance over the shelves, as if scrutinizing for clues.

Macel was captured by Waheed’s Our Naufrage paintings, which depict waves of blue water.

“She had seen and fallen in love with them last year when she came upon them,” said Waheed. “Macel had seen other works of mine, but those ones were something that were really important for her to include in the show.”

Waheed’s work has shown widely. A finalist for the 2016 Sobey Art Award, Waheed has had solo exhibitions at institutions including the BALTIC Center for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, Mosaic Rooms in London and Darling Foundry in Montreal, and been included in group shows at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Kunstsaele Berlin and more.

Visitors to the Venice Biennale are welcome to step up on specially made stools to view some of the works in Hajra Waheed’s installation. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

Visitors to the Venice Biennale are welcome to step up on specially made stools to view some of the works in Hajra Waheed’s installation. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

The overall effect of Waheed’s Venice installation—with bodies of work horizontally mounted, one leading naturally into the next—certainly suggests that careful looking will yield insight.

“There is a sense of repetition and a desire to catalogue within my work,” said Waheed. “I want to categorize the chaos; create a certain sense of order to it.”

Waheed’s desire is undoubtedly achieved, and her sense of order, particularly within Macel’s “Pavilion of Joys and Fears” (one of nine sections in the larger “Viva Arte Viva” exhibition)—which brings together artists who highlight, in the curator’s words, “new feelings of alienation due to forced migrations or mass surveillance”—has a kind of clarity and precision that mounts a prophecy.

To be in Venice, surrounded by ever-rising water, it would be difficult not to interpret Waheed’s work as an experience of displacement already undergone by many, as well as a warning of what the future may hold.

A closer view of Hajra Waheed’s Our Naufrage 1-10 (2014), a series of small paintings of blue waves, at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

A closer view of Hajra Waheed’s Our Naufrage 1-10 (2014), a series of small paintings of blue waves, at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.