In the summer of 2015 the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean had reached a breaking point and the Western news media was, at last, reporting on the thousands of people attempting to escape unliveable conditions by transiting north across the sea—images of overcrowded boats, and bodies washed ashore, were circulating regularly. In this context of humanitarian crisis, Hajra Waheed’s exhibition “Asylum in the Sea,” at Montreal’s Darling Foundry, felt timely, revealing the paradoxes of asylum-seeking with quieter urgency than the drama so often instrumentalized in photojournalism. In the entrance, three etchings on transfer paper, Still Against the Sky 1-3 (2015), each contained a galaxy of stars and were marked by the creases of wellworn fold lines, like a map opened and closed many times. In the larger gallery, 24 postcard-size works on paper were mounted to 12 chest-high triangular wood supports that recalled grave markers or stelae. On one side, each work depicted fields of painted grey dots resembling the static noise or snowy resolution of old television sets with bad reception; on the other side were tiny collages made from photographs of waves, with drawn circles and diagrams, arrows and grids, annotations and coordinates pointing toward something possibly missing. The letters and numbers referred to specific frequencies used to send out distress signals, but to an uninitiated viewer the codes remained obscure, embedding within the work unanswered calls for help, furtive networks of escape, oceanic navigation by starlight, and risk. Among these lost signals, one could read the global conditions of the current moment when, even with technologically advanced surveillance capacities, denial is a political strategy.

Timely though it was, “Asylum in the Sea” was actually part of an ongoing project Waheed began years prior: Sea Change (2011–) is a visual novel that chronicles the disappearances of nine characters, told through nine chapters, most yet unmade. Planned by the artist as a lifelong project, it reveals familial connections that reach across time and space—narrating stories of loss and longing. Avow 1-38 (2017) is the newest addition, a series of delicate paintings on tin commissioned by Christine Macel for the 2017 Venice Biennale and which is now in the permanent collection of the Centre Pompidou. Waheed’s participation that year (along with Jeremy Shaw and Kananginak Pootoogook) marked the first appearance of Canadian artists living or deceased in Venice’s main exhibition in more than a decade, and for Waheed it was a significant milestone achieved without the support of commercial representation.

The paintings in Avow use the natural elements as cosmic markers of time: storms moving across water, moonlit mountain ranges, a series of smoky fires set by accident or explosion, a cave, a waterfall, starry nondescript skies, hands cupped in offering or prayer and one figure, a woman, whose back is turned. Projecting human struggle onto land and landscapes, these small paintings are proclamations—avowals—that even in the deepest separations, one can bear hope. Such mysterious, interpretive qualities are emblematic of Waheed’s practice. On returning to painting, she says that she “always feels equal parts terrified and in awe” of it. This could be because of the way painting necessarily depicts an imaginary world, one that is neither pure fantasy nor purely representational. Avow presents us with a world in glimpses—flashes of scenes that feel unexpectedly familiar but that we somehow can’t quite place.

Though trained in drawing and photography, Waheed is truly a multidisciplinary artist, working with sculpture, sound, installation and video. And her method of working does owe something to the legacy of painting, a medium that so often defines how we experience art. She typically collages painted, drawn or photographic elements to the verge of abstraction and, when viewed in aggregate, broader political valences and visual narratives in the works unfold. This quality of incorporating recognizable but non-representational imagery is critical to Waheed’s practice: she uses abstraction to try to understand something about the mechanics of seeing, to defamiliarize what seems obvious and to project what is yet to come. Across frequent references to technologies of vision and orientation (satellites, aerial imagery, GPS coordinates, infographic scans, topographic maps) there is a simple yet palpable human presence: a hand-cut photograph, a folded page, a singular brushstroke or pencil mark, a well-handled and time-worn object. Such material intimacy runs counter to the digital automation of uninterrupted, never-ending image streams: it arrests our looking. Hers is a slower yet powerful impulse toward finding moments of beauty and respite even under the most violent conditions, but it’s a beauty that still, somehow, resists the aesthetics and chaos of an increasingly militarized world.

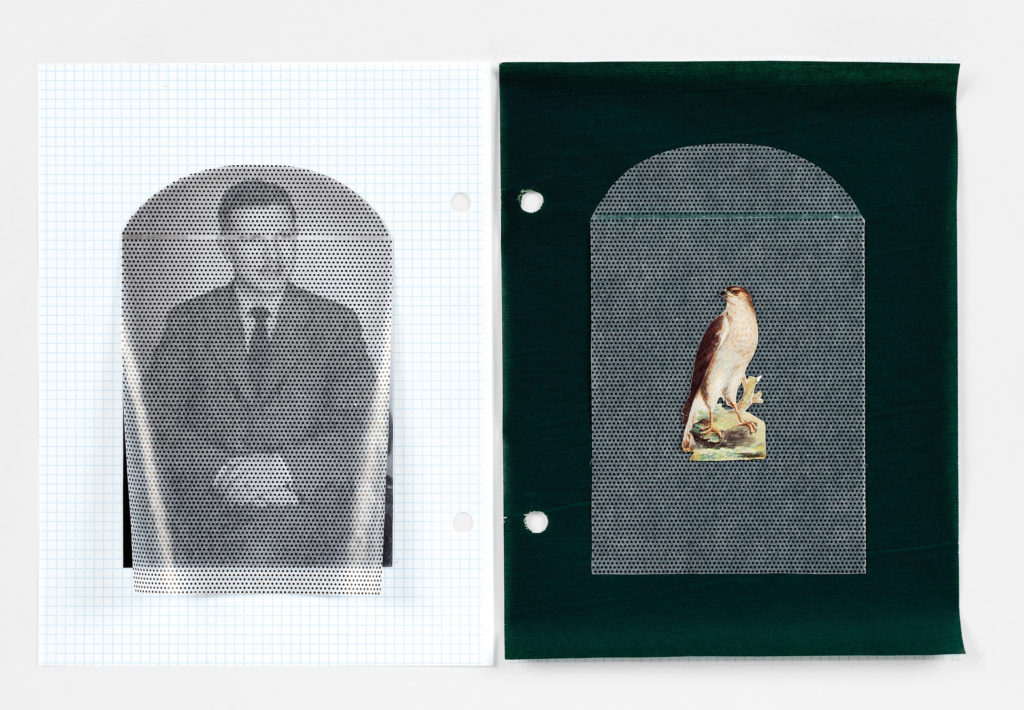

Hajra Waheed, The ARD: Study for a Portrait 1-28 (detail 2/28), 2018. Mylar, photographic collage, archival tape on transfer and graph paper, 35.6 x 46 cm framed. Courtesy the artist.

Hajra Waheed, The ARD: Study for a Portrait 1-28 (detail 2/28), 2018. Mylar, photographic collage, archival tape on transfer and graph paper, 35.6 x 46 cm framed. Courtesy the artist.

WAHEED GREW UP between several continents. Born in Calgary to first-generation Muslim-Indian parents, she spent her formative years (from the early 1980s to the early 2000s) living in Dhahran, the heavily secured corporate headquarters of the state-owned Saudi Arabian Oil Company, or Aramco. “My family has a long and complex history of migration between South Asia and the Middle East that spans generations,” says Waheed. “Some crossed as migrant labour, others for love, others to flee. My father had four brothers who had already been living in Saudi Arabia when he received his job offer. It was that or driving cabs. He took it.” Aramco is one of the largest oil and gas companies in the world, with an annual revenue of more than USD$350 billion and, in 2018, a value in excess of several trillion (although the precise valuation has been questioned). Its headquarters include four residential communities built for employees; the first and largest, known as “Dhahran Camp,” was built in the early 1940s and is modelled on the typical American suburb, complete with tree-lined streets and imported grass lawns. Waheed’s father worked in mineralogy and extraction, poring over seismographs to determine the viability of current and future wells. Like other company families, they lived with gated security and under constant surveillance. It meant that Waheed’s early experiences of the world were highly restricted; civilian photography was not allowed, which led to her early fascination with other available technologies—flight tracking, aircraft identification, deciphering maps and the machinations of extraction. For Waheed, understanding the verticality of the view from above and the power of reading the earth below became foundational.

Whether in Alberta, Saudi Arabia or elsewhere, immigrant experiences and career options are often different for women than for men. “My mother was an abstract painter, but she stopped as soon as I was born. She didn’t feel it was possible, financially, to do it and raise all of us at the same time. Her reticence to pass it on to me was folded into her anxieties about passing on the potential disappointment of that journey. Still, she imparted her love of colour and thinking through abstraction, and at a very early age.”

Waheed also shares with her mother the perceptual phenomenon known as synesthesia. Synesthesia can take many forms, but in this case both have a unique capability to sense colours in unusual ways. “Ever since I can remember, if I don’t see a specific colour that I’m craving in a given day, I’ll seek it out. I’ve always thought this was normal. To smell or taste colour. I never considered it a condition, but it does change your sensory perception. Your senses are elaborated upon and heightened because you’re using two, sometimes three senses simultaneously.” These uncommon experiences of abstract beauty—the desire for colour and inherited synesthesia—and of making a life in one of the most highly surveilled and restrictive states in the world, are tendencies that mark out the edges of an expansive art practice.

There is a simple yet palpable human presence: a hand-cut photograph, a folded page, a singular brushstroke, a time-worn object. Such material intimacy runs counter to the digital automation of our world: it arrests our looking.

Still, she says there was no defining “aha” moment in becoming an artist. “I spent a long time fighting it actually. Drawing was a daily practice and a survivalist strategy, inherent and intuitive. I never stopped. It’s always remained so limitless and boundless.” From this early expression came what she calls “the exploding book form”: the de-paginating and re-combining of materials that would typically be sequenced and bound. One of her first exhibited series, The Scrapbook Project (2010), came from this way of working and remains ongoing. The later and more complex KH-21 (2014), which was based on declassified information about American photographic reconnaissance satellites launched between 1971 and 1986, does this too: each uses the seriality of the notebook and the predictability of the grid to orient the viewer around the disorienting effects of surveillance regimes.

More recently, The ARD: Study for a Portrait 1-28 brings Waheed’s interests in mining archives, printed matter and the complexities of corporate-state relations into full view. In 2018, Waheed was commissioned by the Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai to work with the official archives of Saudi Aramco. The “ARD” of the title stands for Aramco’s Arabian Research Division, which was founded in 1946 as an intelligence-gathering unit following a series of workers’ strikes a year earlier. Embedded within the company and led by Berkeley-educated American Arabist George Rentz, the ARD was instrumental in setting the territorial limits of the country, monitoring and quelling social movements, and producing de facto historical narratives by publishing and distributing a wide variety of scholarly material, policy reports, fact sheets, maps, magazines, encyclopedia entries and films. Aramco was sophisticated in how it used culture as a specialized, corporate form of propaganda, recognizing the need for a cultural legacy that would legitimate its role in the region. Aramco World, for example, was a free magazine established by Aramco in 1949 and has published continually since, with a mandate to “increase cross-cultural understanding by broadening knowledge of the histories, cultures and geography of the Arab and Muslim worlds.” From its inception, Aramco World disseminated particular historical narratives about the country and region that have, until very recently, been widely celebrated as evidence of its modernist past.

Collapsing together archival documents from this little-studied history of extraction, and using what has become a signature combination of photography, cut paper, annotations and transparencies, Waheed reconstructs key elements of the ARD—surveyors mapping landscapes, aerial views depicting rows of block housing, base camps, surveillance of labourers and workers’ walkouts—across a series of 28 works on paper. The mysterious aspects of some of the works (What are “Boundary Studies”? Is the man in the collage with the falcon George Rentz?) and their analog qualities (graph paper, binder holes) suggest a parallel with the loose physicality of archives, where an interpretation of events might be based on folders of neatly clipped documents, unannotated photographs, handwritten notes and mislabelled, misfiled or missing material. The ARD: Study for a Portrait intervenes in official narratives to re-form them into new texts and subtexts, revealing just how much an “official” history can itself be manufactured. Offering enough clues to map out a story, the series treads a line between fact and fiction, and calls to question how Aramco did the same, creating its own myths in order to maintain control in the region as a powerful but seemingly benevolent force.

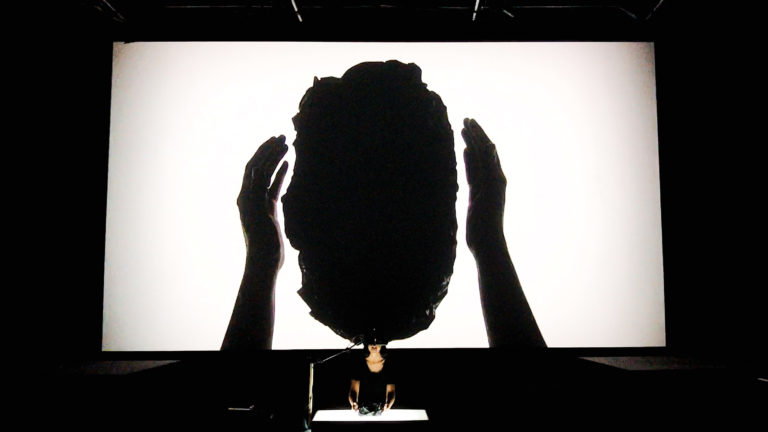

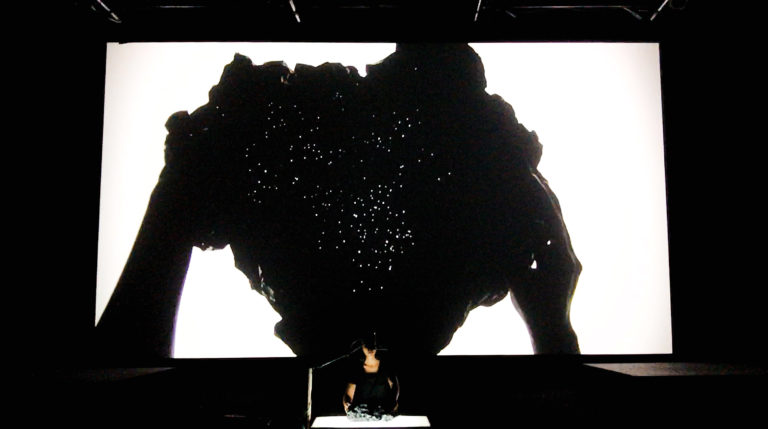

Hajra Waheed, Hold Everything Dear, 2017. Performance still, “FIELD MEETING Take 5: Thinking Projects,” SVA Theatre, New York. Courtesy the artist.

Hajra Waheed, Hold Everything Dear, 2017. Performance still, “FIELD MEETING Take 5: Thinking Projects,” SVA Theatre, New York. Courtesy the artist.

Hajra Waheed, Hold Everything Dear, 2017. Performance still, “FIELD MEETING Take 5: Thinking Projects,” SVA Theatre, New York. Courtesy the artist.

Hajra Waheed, Hold Everything Dear, 2017. Performance still, “FIELD MEETING Take 5: Thinking Projects,” SVA Theatre, New York. Courtesy the artist.

WAHEED’S WORKS have been widely collected by institutions such as the British Museum, MoMA, Devi Art Foundation in New Delhi, National Gallery of Canada and the Art Institute of Chicago, although they’ve been shown less in Canada. This fall she’s participating in the inaugural Toronto Biennial and has her first solo exhibition in Toronto, at the Power Plant, for which she is producing all new work, including a site-specific installation, more than 100 individual paintings and works on paper, video, sculpture and a series of clay objects. Titled “Hold Everything Dear,” the exhibition refers to art critic and novelist John Berger’s collection of essays by the same name, in which he reflects on survival and resistance during the fractured years pre- and post-9/11. Waheed says that her new works, “are meant to act as a meditation on undefeated despair and the possibilities for radical hope. Many of the works, often punctuated with prose, visualize alternative ways of resisting or overcoming tides of violence. Some are meant to challenge our perceptions while others suggest ruptures through transference from one state of being to another.”

“Hold Everything Dear” began as a 10-minute performance at the SVA Theatre in New York, as part of Asia Contemporary Art Week in 2017, and later at the Sharjah Art Foundation’s annual March Meetings. It was the first time Waheed had collaborated with her sister, Sarah Waheed, a cultural historian and professor at Davidson College in North Carolina. In it, Hajra reads a letter from Sarah, dated to a few years prior, while manipulating an opaque form over a light box that is being live-streamed on a screen behind her. As light spills out around the large, dark form, a story of exile unfolds: “And so you recite lines of poetry in your head, about homes you have left behind. Homes you will never return to. Homes for which it has been such a long time for which you have yearned, that you yearn no more. And you think, what a long time it has been, that you have yearned to return.” The shadow comes to feel heavy, like a monolith with its own strange energy, condensing frustration, hope, anticipation, beauty and violence at once. Eventually Waheed opens it up, unfolding it to stretch across the now-dark screen, save for the small points of starry light.

Waheed’s work returns storytelling to visual form, through recourse to personal accounts of migration, technology and the economic politics of an energy-hungry global power. It’s rarely a linear story, but good storytelling seldom is.

The performance shares first-hand accounts of the cycles of generational trauma associated with exile against a backdrop of state-led efforts to institutionalize the “othering” of Muslims. But, like much of Waheed’s work, it does so with a poetic sensibility that counters the desperation of current politics. What does it mean to hold everything dear? To maintain courage and love against the violence of perpetual war? It’s an elegant response to Berger’s work, which also uses the form of letters—dispatches— to articulate relationships formed through separation and radical action. Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark was also a touchstone. Reflecting on the necessity of hope as a tool of resistance in a world that seems to demand nihilism, Solnit writes: “Change is rarely straightforward… Sometimes it’s as complex as chaos theory and as slow as evolution. Even things that seem to happen suddenly arise from deep roots in the past or from long-dormant seeds.”

Waheed’s work reminds us of this possibility, returning storytelling to visual form through recourse to personal accounts of migration, technology and the economic politics of an energy-hungry global power. It’s rarely a linear story, but good storytelling seldom is. Instead, she guides us with a counter-map of sorts, charting her experiences but giving us the space to think about our own—our own relationship to distance and diaspora and the chaos of the universe. Her projects are like constellations: making connections we might not have made otherwise, constructing stories in the spaces between points of obfuscated light, reminding us of the humanity built into our technologically determined worlds. It’s a practice that asks us to pay closer attention, to challenge our own imaginative ends and to think about our culpability within the systems of injustice.