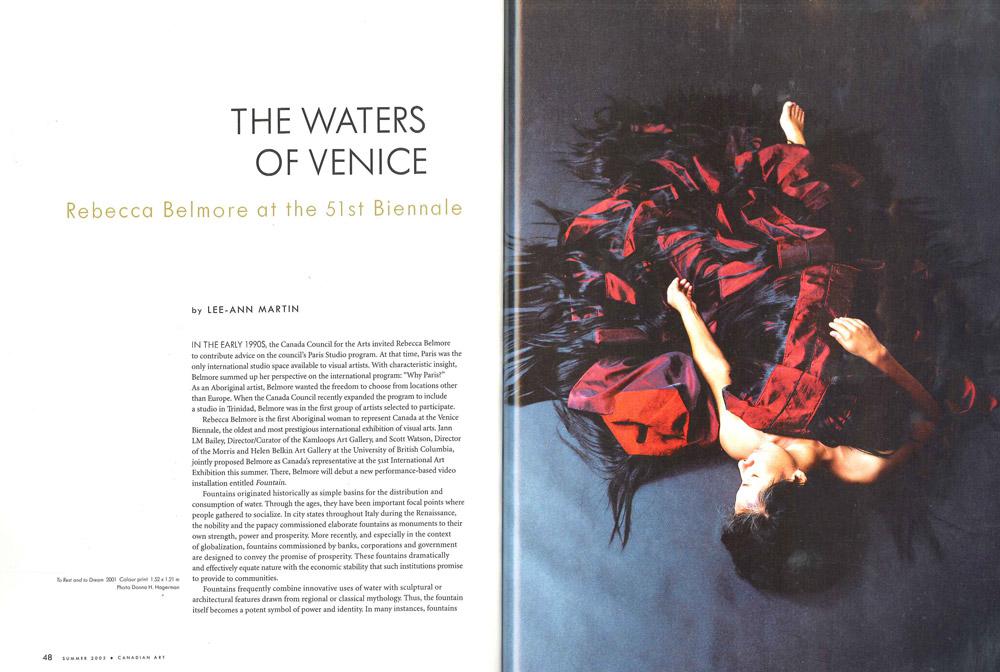

In the early 1990s, the Canada Council for the Arts invited Rebecca Belmore to contribute advice on the council’s Paris Studio program. At that time, Paris was the only international studio space available to visual artists. With characteristic insight, Belmore summed up her perspective on the international program: “Why Paris?” As an Aboriginal artist, Belmore wanted the freedom to choose from locations other than Europe. When the Canada Council recently expanded the program to include a studio in Trinidad, Belmore was in the first group of artists selected to participate.

Rebecca Belmore is the first Aboriginal woman to represent Canada at the Venice Biennale, the oldest and most prestigious international exhibition of visual arts. Jann LM Bailey, Director/Curator of the Kamloops Art Gallery, and Scott Watson, Director of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia, jointly proposed Belmore as Canada’s representative at the 51st International Art Exhibition this summer. There, Belmore will debut a new performance-based video installation entitled Fountain.

Fountains originated historically as simple basins for the distribution and consumption of water. Through the ages, they have been important focal points where people gathered to socialize. In city states throughout Italy during the Renaissance, the nobility and the papacy commissioned elaborate fountains as monuments to their own strength, power and prosperity. More recently, and especially in the context of globalization, fountains commissioned by banks, corporations and government are designed to convey the promise of prosperity. These fountains dramatically and effectively equate nature with the economic stability that such institutions promise to provide to communities.

Fountains frequently combine innovative uses of water with sculptural or architectural features drawn from regional or classical mythology. Thus, the fountain itself becomes a potent symbol of power and identity. In many instances, fountains have become universal monuments to our fascination with water, even as we deplete and defile this life-giving natural resource.

Belmore seeks to shatter long-held myths embedded in our common history in order that her Fountain can become a symbolic oasis in the arid environment of colonial relations. Great fountains help to memorialize people and places, and memory is important to Belmore. The city of Venice is also emblematic of the 500-year history of the European colonization of the Americas. Located in the country of Christopher Columbus, it is part of the colonial story. A shipping port, an island city built on water, it has been a conduit for European world views. In the so-called Age of Discovery, an era of innovation in the arts and sciences, society and government, elaborate fountains were popular in Venice, as they were in other Renaissance centres. In 1492, Columbus navigated from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean in search of a trade route to the East Indies. His landfall on the shores of the Americas is well documented. However, the impact of his landing upon the European world view at that time may be less obvious. The voyage revealed a continent and peoples previously unknown to Europeans, who believed, as Columbus did, that there was an unobstructed expanse of water leading west from Europe to the Indies. The existence of the Americas challenged not just this premise but many other accepted hypotheses. For many European thinkers, the Americas symbolized a new freedom that transcended existing intellectual boundaries and provoked a boundless expansion of power across newly controlled oceans.

Fountain is quintessential Belmore. Her reputation, across Canada and internationally, has been earned with performances and installations that reveal sensitivities to history and place, memory and absence. Early national attention came to her in 1987 in Thunder Bay, Ontario, where she lived at the time. Rising to the Occasion, now in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, was a dress that simulated a beaver house and which figured prominently in the parade and video performance Twelve Angry Crinolines, staged on the occasion of a royal visit to the city by Prince Andrew and his new wife. The following year, Exhibit 671B, a performance outside Thunder Bay Art Gallery, was a critical response to issues surrounding the exhibition “The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples,” organized by the Glenbow Museum in conjunction with the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary. The exhibition presented historical objects borrowed from national and international ethnographic museums. The Lubicon Lake Indian Nation in northern Alberta generated support from Aboriginal artists and communities across the country for its widely publicized boycott of the exhibition, angrily condemning the non-Aboriginal organizers of the exhibition for perpetuating the romanticization of Aboriginal cultural history while denying the complex contemporary realities of Aboriginal communities. In 1992, Belmore began a Canada-wide collaboration with Aboriginal people, travelling to communities across the nation with a huge wooden megaphone titled Ayumee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother, through which individuals addressed the Earth.

Usually site-specific and often based upon immediate experience, Belmore’s mixed-media installations expand upon traditional notions of sculpture. Her relationship to place and history, identity and circumstance is central to her multidisciplinary practice. Fountain brilliantly exemplifies her manipulation of materials and concepts into innovative spatial environments. Ultimately it also becomes a respite from the frequently hostile terrain of colonial history.

The Venice Biennale dates from 1895, in the era of the great world fairs. These large international expositions were developed as opportunities for both the exchange of ideas and the patriotic display of artistic and technological innovation. Spectacular public fountains again gained prominence within these symbolic extravaganzas of industrial and colonial expansion.

The work also connects Venice with Vancouver, where Belmore currently lives. The cities share a seeming abundance of water that defines the distinctive identity of each and enables sustenance, pleasure and commercial exchange. As busy ports, Venice and Vancouver are linked in the self-perpetuating cycle of global commerce. Iona Beach, south of Vancouver, where the city’s sewage is released into the ocean, is where Fountain was performed by Belmore and shot on video by the renowned filmmaker Noam Gonick. The video begins with a panoramic view of a heavily overcast sky and a wide expanse of grey ocean. One must look closely to discern the sewage pipe at the horizon line, but the sound of a jet from a nearby airport clearly disrupts the primordial, untouched aura of the scene. The camera moves quickly along a stretch of sandy beach that is strewn with timber rescued by the water from the logging industry’s greed. Suddenly, brilliant fire bursts skyward from the beach.

In the frigid water, Belmore struggles with the full bucket that she carries. The burden implies an ongoing, futile battle. It is a reminder that the oceans carried Europeans to the Americas and were witness to the shock waves of their arrival. The bucket bears the weight of historical circumstance. The turbulence subsides. Belmore hauls the bucket onto the beach and strides with great resolve toward the camera. She heaves its contents toward the viewer. The water becomes blood. It flows down the screen, turning it into a monochrome painting. Through the bloodied surface, Belmore confronts the camera with a sombre, resilient look. It is the expression of someone ready to move forward, with nothing to fear and, sadly, nothing more to lose. The blood and water merge to become tears that recall the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama: “. . . until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

The blood in Fountain is a powerful metaphor for the burden of First Nations history. Here, as throughout Belmore’s art, she flings responsibility for the cycles of bloodshed found within the history of colonialism in the Americas back to their European source. Through her actions, an Anishnabe woman from northwestern Ontario recognizes the blood of all people who suffer because of others’ greed for power.

An earlier performance, Bury My Heart (2000), in Great Falls, Montana, responded, in part, to the massacre of 300 Oglala Sioux by the United States Army in December 1890. In that work, Belmore’s repetitive smearing of blood on a chair and of mud on her thrift-shop dress further addressed the history of violence against Aboriginal women. Both the 19th-century massacre at Wounded Knee and the 2002 discovery of the remains of dozens of missing women, many of them Aboriginal, at a pig farm outside Vancouver were the subjects of Belmore’s installation blood on the snow, created in 2002 for the exhibition “The Named and the Unnamed,” organized by the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. The work, which toured Canada with the show, presents a pristine white blanket of snow defiled by the blood of the dispossessed. Blood running down a white chair at the centre of the blanket seems to stand for pain and violence in the midst of cold, white indifference. For Belmore, it is an extension of ongoing violence against Aboriginal people.

The elemental aspects of Fountain align closely with a previous installation, Paradise, created for the 11th Biennale of Sydney in 1998. There, Belmore encased in glass numerous individual photographs of stones and water, clouds and sky. Installed to resemble stepping stones, the work imagined an elegantly fabricated paradise comprised entirely of elements of nature. With Fountain, Belmore, adding to her consideration the enormous weight of history and memory, again addresses our complex relationships with water. Populations can grow and develop only in close proximity to adequate and potable water supplies. (During Belmore’s participation in the Biennale of Sydney, the city declared the water unsafe to drink. Hotels were forced to supply bottled water to all guests, while residents boiled their tap water.) Subterranean infrastructures of pipes route water to our faucets; another system of pipes transports our effluent back to water. In reality, water’s scarcity means that we fight one another for control of this essential commodity in the name of corporate and economic expansion and, for some, survival. Multinational companies operate in underdeveloped areas throughout the world, devouring an ever-increasing portion of the globe’s water. This is currently the case in, for example, Plachimada, India, where local villages suffer severe water shortages because Coca-Cola makes a practice of drawing large quantities of water from the area’s deep-bore wells. Additionally, effluent from the corporate leviathan’s bottling plants contaminates the soil and local wells. The area’s tribal councils are forced to fight back; they demand that rights over water must be linked to the broader struggles of marginalized people.

In another water-based work, Temple, installed at The Power Plant in Toronto in 1996, Belmore addressed the perceived abundance, sources and quality of drinking water. She collected 3500 litres of water from various sources, including Lake Ontario, the polluted Great Lakes basin upon whose shoreline The Power Plant is located. She stacked plastic bags full of water in the shape of a pyramid and installed a functional drinking fountain on a raised platform near a peephole with a telescope aimed at Lake Ontario. For the performance Reservoir (2001), in Vancouver, Belmore filled 13 tubes made of plastic bags with Vancouver tap water, then installed them side by side beneath video images of fountains throughout Vancouver.

European art history offers many images of women fetching and carrying water; the symbolism rests in the relationship between the conventional nurturing role of women and the life-giving qualities of water. In Fountain, the bucket that Belmore carries also carries her own childhood memories of fetching water. Buckets are perhaps the first tools that humans used in their efforts to control and exploit the power of water. In The Indian Factory (2000), performed in Saskatoon, Belmore entered a space carrying a bucket of plaster, which she then applied to several men’s jackets hanging from hooks on the wall. The hollow and hardened plaster forms were an acknowledgement of Aboriginal victims of ongoing racial violence in the prairie city. In Vigil (2002), she used a bucket of water to wash a sidewalk in Vancouver. The action responded to a need to cleanse the space as a performative memorial to the scores of women who had disappeared from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

Fountain honours the memory of people whose lives have been lost to hostile and violent intentions. The work is situated in the historic tradition of commemorative fountains and monuments, which typically exist in public spaces to prompt an emotional response to aesthetic manipulation of water. Throughout the world, commemorative fountains bear the names of heroic individuals and serve as sites of mourning. They are gestures made by the living in the name of the dead. Belmore’s Fountain offers the power of water as hope. Beyond its veil of blood, it launches new ideas of nature and history into European cultural and intellectual space.

This is a feature article from the Summer 2005 issue of Canadian Art.

A spread from the Summer 2005 issue of Canadian Art.

A spread from the Summer 2005 issue of Canadian Art.

Rebecca Belmore, Fountain, 2005. Single-channel video with sound projected onto falling water, 274 cm x 488 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Fountain, 2005. Single-channel video with sound projected onto falling water, 274 cm x 488 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Rebecca Belmore.