So what exactly was/is the story behind CEAC? Before going any further, it’s important to acknowledge that the record is not a complete blank. York University holds an extensive archive of correspondence, photos, printed matter and CEAC ephemera. In 1986, just a few years after CEAC was unceremoniously disbanded, C Magazine published “The CEAC Was Banned in Canada,” a sweeping “tragicomic opera in three acts,” by Dot Tuer. Monk’s “Battle Stances: General Idea, CEAC, and the Struggle for Ideological Dominance in Toronto, 1976–1978” appeared in Fillip almost 30 years later, coinciding with his chapter treatment of CEAC in Is Toronto Burning? (not to mention the focus on CEAC in the 2014 exhibition he curated, of the same name). And experimental filmmaker Mike Hoolboom maintains a comprehensive online archive of CEAC-related articles, rare photos and otherwise unpublished interviews with some of the Centre’s main players.

From this research and writing—the titles of Tuer’s and Monk’s articles hint at the controversy and drama—it’s possible to form a composite if fragmentary picture of the CEAC story. It begins in 1970 when Italian émigré Amerigo Marras, with American draft dodger and Rochdale College dropout Donald Suber Corley and American gay-rights activist Jearld Moldenhauer, formed the Art and Communication group and what would become the critically influential LGBTQ magazine The Body Politic. By 1973, Moldenhauer had moved on to focus on The Body Politic and Glad Day Bookshop, while Marras and Corley launched the Kensington Art Association (KAA), “a continuous collective experiment in living and in sociological infiltrations with practical demonstrations,” as Marras would later describe it.

It’s here that the Marxist-driven ideological roots and multiplatform, international interests of what would soon become CEAC began to evolve. Then based out of the trio’s 4 Kensington Avenue home, the inaugural KAA exhibition in October 1973 featured French architect and urban planner Yona Friedman, which included a manual for children on conceptual building strategies and the magazine Super Vision, which as Tuer writes, “encompassed the possibility of translating architectural language into user-friendly, computerized design, and an analysis of the relationship of architectural imperialism to conditions in the Third World.”

Following the fall 1975 exhibition “Language and Structure in North America,” organized as a “visual and literary manifesto on aspects of language, art, and structuralism” (Tuer), and the January 1976 exhibition “Body Art,” inspired in part by the extreme performance work of Viennese Actionist Hermann Nitsch, plus a brief move to 86 John Street, KAA became CEAC. In September 1976, Marras, Corley and a core group of artists, including Bruce Eves, Ron Gillespie (now Ron Giii), Diane Boadway, Peter Dudar and Lily Eng (a.k.a. Missing Associates), John Faichney and Wendy Knox-Leet, set up shop at 15 Duncan Street in a four-storey industrial building purchased with a $55,000 lottery grant (roughly $238,000 in 2019).

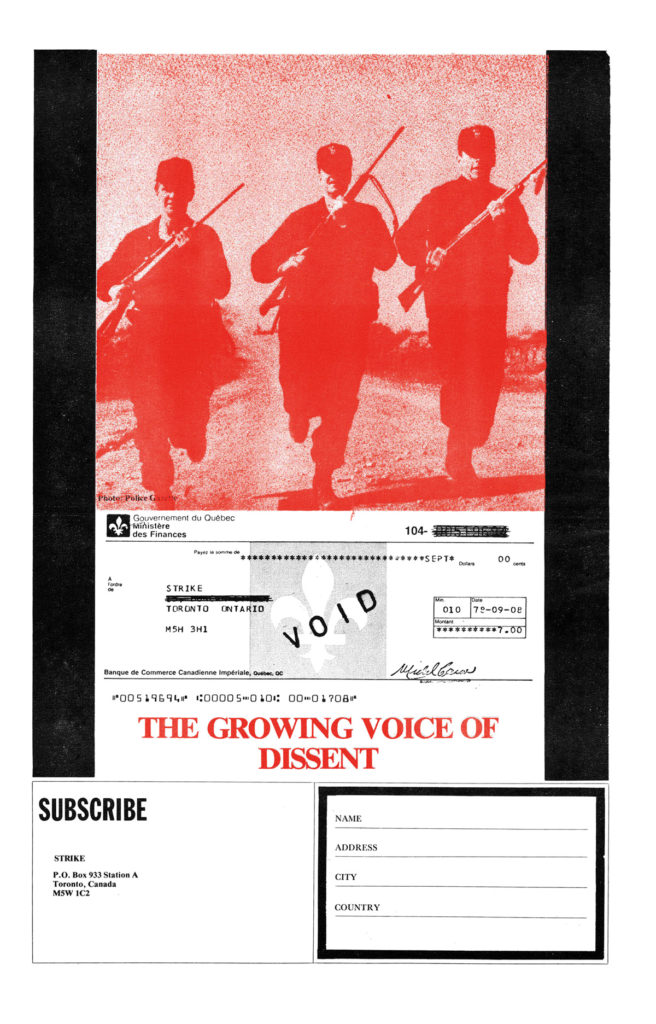

Subscription ad for the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication’s Strike 3, October 1978.

Subscription ad for the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication’s Strike 3, October 1978.

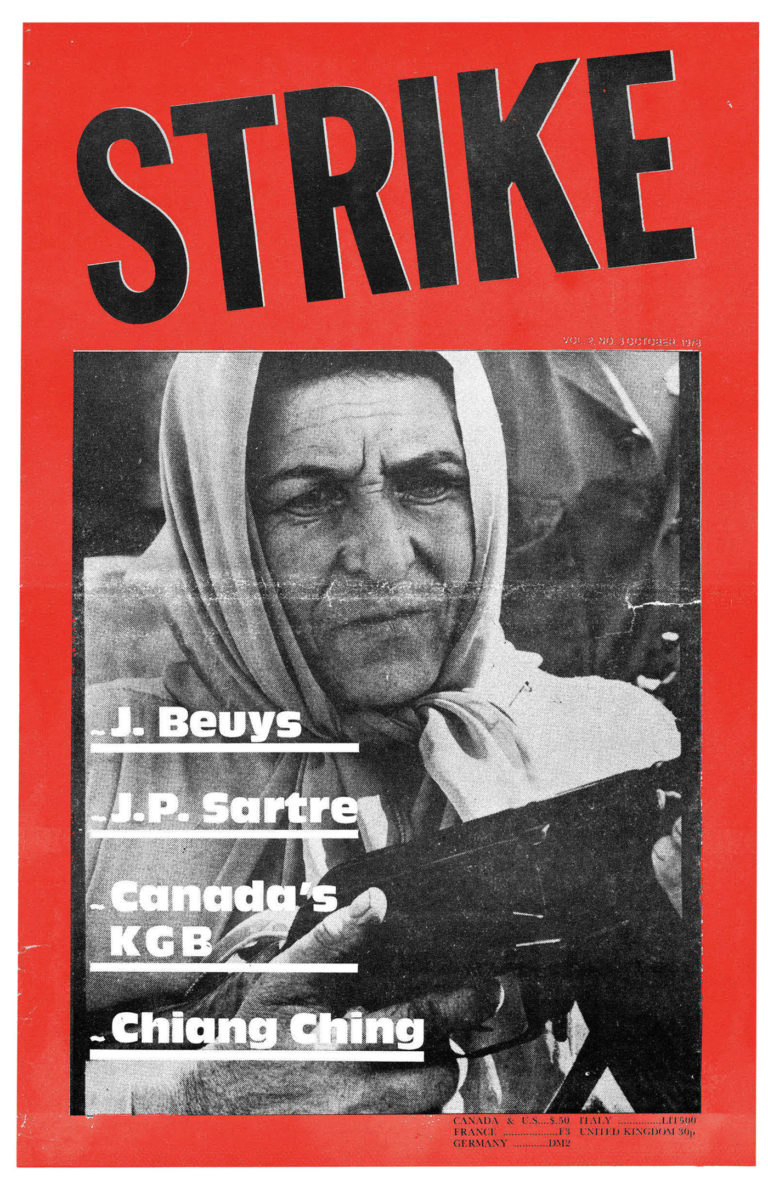

Cover for the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication’s Strike 3, October 1978.

Cover for the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication’s Strike 3, October 1978.