Yaniya Lee: Not long after you started as chief curator at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, you began researching the history of Victoria’s racialized communities. At the time, you said you wanted “to figure out how to create a strategic direction for the kind of institution that allows us to talk about all of us who live here, and what it means for us to be here together.” How was your time at the AGGV and what do you feel you achieved there? Was Victoria responsive to these conversations?

Michelle Jacques: Most of Victoria was very responsive to the conversations. Although it’s not the most diverse community, Vancouver Island is a region where people are very committed to social issues. Just after the 2019 election, I was sitting in a pub in downtown Victoria, and Jagmeet Singh walked past—all of the bearded white hipster boys saw him and just went crazy. Many people in the city lean left politically, and I found an unexpected kind of openness to a diversity of art work and an interest in complicating whose work gets shown.

However, there was a small community of people who felt strongly about the AGGV remaining apolitical and didn’t support the way the program was moving. But I would say that the general public was extremely responsive and really interested in these new ideas. Something that I learned early on was that if you polled ten people about what they wanted to see at the AGGV, eight of them would have said Emily Carr. But if you dug a little deeper, asked a few more questions, you’d learn that what they wanted to see was work by artists who, like Carr, told stories they could relate to, because there was some connection, a relevance to their experience in Victoria and on Vancouver Island. So that’s what we did. There was always a way to situate things and communicate what the local tie was.

My practice has long been committed to public institutions and major mainstream institutions, and working hard to expand who has access to them.

In 2016, I did an exhibition at the AGGV with two artists from up island: Klehwetua, Rodney Sayers, who is a Hupacasath artist from Ahswinis, Port Alberni, and his partner, Emily Luce. They built a functioning structure that was a combination of a sauna and a smokehouse. A few months before their own show, the work was presented as an intervention in Gwen MacGregor’s exhibition Circumstance, which she had created in “The Mansion,” the colonial house that was the original home of the AGGV, and which still forms part of the building. Before they brought the work to Victoria, they spent days in the sauna, and while they were saunaing they smoked something like 40 pounds of salmon, so the structure smelled like salmon when it arrived. It was a really interesting talking point: this traditional Indigenous structure, the smokehouse, combined with what is essentially a traditional European structure, the sauna. In a subtle conceptual way, its presence asked the question: Why did these Brits come to an island which is rainforest and giant trees and decide that colonial British houses were the thing to build?

YL: Do you have a personal mandate? Is there a through line of artists and practices that you want to present in the places you work?

MJ: I think over the years really what happened was that my mandate became more about opening up institutions than about having a clear focus on a particular kind of curating.

Working in the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Contemporary Department back in the 2000s, I remember having a discussion with my colleagues about how homogenous the participation in our project series would have been if I wasn’t including BIPOC, women or LBGTQ artists. I couldn’t even say that I was really focused on Black artists—generally, within the idea of challenging the institution, I’ve tried opening it up—and yes, that has definitely been about expanding the representation of artists. That expansion was a particular focus of our work at the AGGV, and it was a great privilege to lead a team who was also interested in doing that.

Grafton Tyler Brown, Sunset at Stave Lake B.C., 1882. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Grafton Tyler Brown, Sunset at Stave Lake B.C., 1882. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

But really, at the most foundational level, I think the thing that identifies my practice is being long committed to public institutions and major mainstream institutions, and working hard to expand who has access to them.

YL: You have experience with collection development and reinterpretation. Could you describe what kind of work that is?

MJ: We didn’t have much of an acquisitions budget in Victoria. We relied largely on donations, so it was hard to shape the collection at the point of acquisition; it was much easier to shape it at the point of interpretation. We did dig through the collection to see what we had that could shift the story a little bit. Upon reopening after the first COVID closure, we installed a work by Grafton Tyler Brown in a collection show of Canadian historical art. We were able to create enough interest out of showing that one work that board members started keeping their eye out for other Grafton Tyler Brown works. We were then able to acquire a new painting of his that one of the board members tracked down with a dealer in Vancouver. That felt like a real achievement. Of course it was an achievement to be able to add historical work by a Black artist to the collection, but that it was a white board member who understood the importance of doing so and helped to identify that kind of work for us also feels really important.

YL: What’s the difference between building a collection and building an exhibition? Is there one format you prefer more than the other?

MJ: I think it’s nicer when they’re very integrated. They were quite integrated at the AGGV, but, for instance, at the AGO, I think particularly about the Canadian Department. During my time there, it had always been my hope that the Canadian Department and the Contemporary Department would be more integrated, so that the stories and narratives were building more cohesively.

I have been speaking to [AGO curators] Georgiana Uhlyarik and Wanda Nanibush quite a bit now because the way it works at the AGO [is that] the Canadian department’s collecting responsibility expands every five years—so now I think the Canadian Department is responsible for Canadian work up until 1995. They were in touch with me to say, you know, all of those artists you were interested in when you worked here and whose work you weren’t able to acquire, let’s talk about how we can acquire them now.

That’s an extreme example of an institution where the exhibition program is what you’re offering people who are coming in the door. It’s the product. And then the collection functions as this archive of Canadian art history. Depending on who was in the curatorial chairs, that can be a very expansive art history or it can be a very limited art history. But at the AGGV, we would have acquired something from every show if we could find the money or attract a donation. That changes from place to place.

I think of the argument that slavery was actually the advent of the modernist period. We have our work cut out for us to really figure out what our definition of modern is going to be.

Historically the Mendel’s collection (the predecessor to Remai Modern) was quite regional. They were definitely trying to build an art history of Saskatchewan. And I think the question now is how to create a mandate that honours that legacy and acknowledges that Remai Modern is the biggest and most resourced institution in the Prairies. There’s a commitment to be made to artists of that region, but we also want to be able to contextualize them within a broader story. And I really think we should be doing that in our exhibitions, too.

YL: Remai Modern has a large modern art collection and a healthy acquisitions budget. This will be in your hands. What are you looking forward to with the collection?

ML: I have to say that the opportunity to work at an institution with a designated acquisition budget was really was a selling feature. In keeping with the name of the museum— Remai Modern—modern art is the purview of the collection, and I think it’s safe to say that I’m really interested—as are co-executive directors and CEO Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh—in troubling how we define the modern. So that’s the first point of order: sitting down with them and figuring out how we’re going to understand what the modern is.

There are all kinds of ways to expand the way we define the modern. I’m not sure if our Remai Modern predecessors were thinking about it in that capital-M, Clement Greenberg Modernism, but I think we are going to push the definition of modernism. I think of the argument that slavery was actually the advent of the modernist period. I think we have our work cut out for us to really figure out what our definition of modern is going to be.

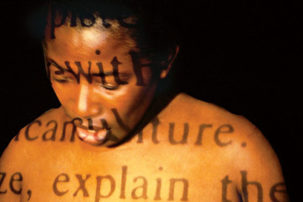

Klehwetua, Rodney Sayers and Emily Luce, Paƛšiʔaƛma (The Fire is Just Starting), 2015. Courtesy Rodney Sayers and Emily Luce.

Klehwetua, Rodney Sayers and Emily Luce, Paƛšiʔaƛma (The Fire is Just Starting), 2015. Courtesy Rodney Sayers and Emily Luce.

One of the things I’m interested in learning how to pursue in Saskatoon is the partnerships and community work. We were quite well resourced at the AGGV in a different way: our Canada Council core funding was really strong. The Council articulated that with this increased funding, we were to be a leader in our community and try and uplift other organizations through collaboration and partnership. We were invited into a project in 2019 with Charles Campbell and Farheen HaQ, two non-Indigenous racialized artists. They have been working together in an ongoing way, thinking through their positions as non-Indigenous artists in Lekwungen Territory, in a place with a very strong Indigenous history and presence. They wanted an opportunity to invest in building relationships with Indigenous artists and community leaders. They had a show lined up at the Legacy Art Gallery, which is a University of Victoria gallery, and the AGGV was able to support the project with additional resources so that Charles and Farheen could take the time to work with Indigenous artists and community members over the course of many months, and compensate for their time. Through this process, Charles and Farheen came to forge a really important relationship with Yuxwelupton Qwal’qaxala (Bradley Dick), who became the third artist in the exhibition. There was no product, no deliverable for the AGGV; we just supported this group of artists and community members to work in this way, and it allowed them to forge relationships that you can’t forge as easily by simply inviting an Indigenous artist and a Muslim artist and a Black artist into a show.

YL: How do all these experiences shape how you think of your job as a curator?

MJ: Last weekend I was on a goodbye walk with Farheen, and she described me as a relationship builder. I appreciated that observation. I had always thought about it from a very personal perspective—for me, yes, it’s about relationship building, and basically all of my relationships other than my family are through the art world and through my work. I thought that I was being selfish, doing my work in such a way that I got to make friends. But it was nice that Farheen acknowledged it as something that is fruitful for other people, too.

This article was updated on April 5th, 2021 to accurately reflect the multiple presentations of Rodney Sayers and Emily Luce’s project.

Charles Campbell and Farheen HaQ preparing the molds for The Ground Above Us, 2019. Courtesy University of Victoria Legacy Art Galleries.

Charles Campbell and Farheen HaQ preparing the molds for The Ground Above Us, 2019. Courtesy University of Victoria Legacy Art Galleries.