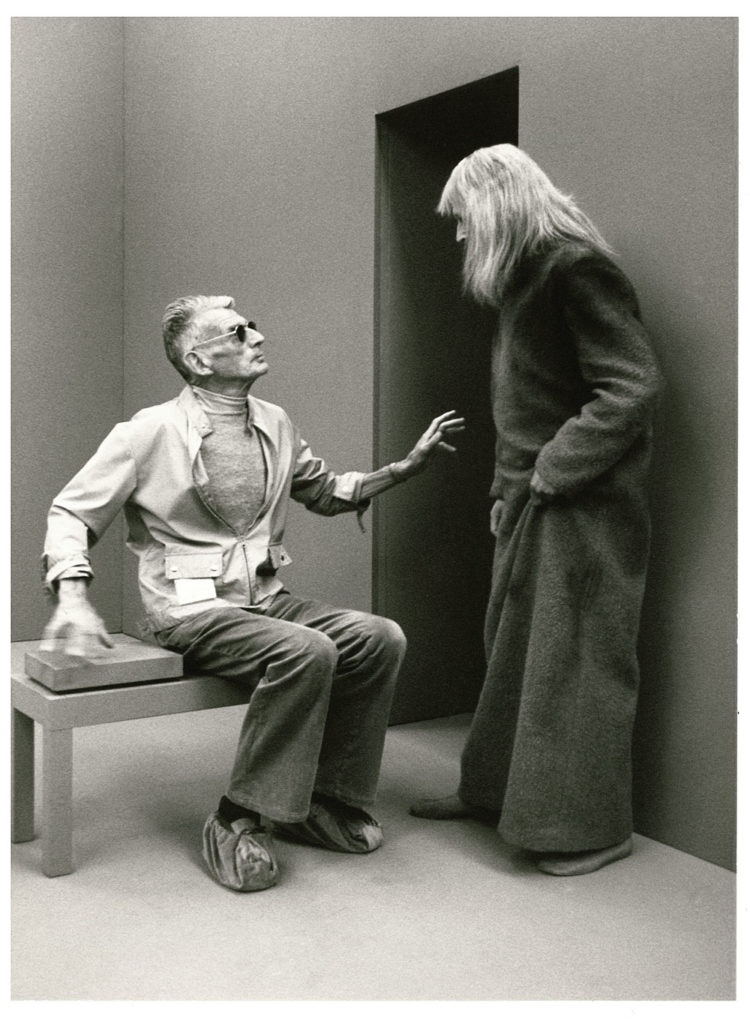

“Fade up to a general view from A. 10 seconds.” So begins Samuel Beckett’s camera direction for his third black-and-white television piece Ghost Trio (1976). The work’s central image is a small, grey chamber populated only by a single male figure clutching a portable tape machine. The figure, seated and hunched over on a simple rectangular bench, has long, white, textured hair and is wearing a floor-length black robe. In the centre of the back wall there is a faint outline indicating a window, and on the floor to the viewer’s left sits a rudimentary bed. “Good Evening. Mine is a faint voice. Kindly tune accordingly,” a monotone, mechanical female voice instructs the viewer. “It will not be raised, nor lowered, whatever happens.” This mechanized voice also appears to dictate the movements of the camera— directing it to shoot the floor, wall, door and window, while also telling the viewer where to look next.

The prescient nature of Douglas’s “Samuel Beckett: Teleplays” and its contribution to the development of international video art has yet to be fully acknowledged.

Here is the ambiguously dystopian world of personal surveillance, artificial intelligence, inertia and alienation that so captivated Vancouver artist Stan Douglas when he first encountered Beckett’s teleplays in the early 1980s. Ghost Trio was originally broadcast in the UK on April 17, 1977, along with two of Beckett’s other television works, Not I (1975) and …but the clouds… (1976), as part of a weekly BBC arts and culture documentary series entitled The Lively Arts. Beckett deliberately circumvented the program’s typical format, an hour-long interview with a single subject, for his own artistic purposes. Refusing to be interviewed, he insisted instead that each of his three television works (two of which he created especially for the broadcast) be aired in its entirety, taking up almost all of the show’s allotted hour of airtime. He stipulated the running order and added the caption Shades to the program’s title. Viewers tuning in expecting to see an informative exchange with the famous writer regarding his well-known plays instead were met with a sequence of highly experimental black-and-white moving-image works closer to video art than traditional drama.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Beckett’s teleplays were generally poorly received by critics and audiences alike. Michael Ratcliffe, drama critic for the Times, reported: “The dynamics are pitched so low that if the plays were any longer you might well drop off.” Sean Day-Lewis wrote in the Daily Telegraph: “Casual viewers who stray into The Lively Arts… tonight are likely to think that something has gone seriously wrong with their [television] sets.” Despite their poor reception, Beckett’s television works were published together in 1977, and it’s in this printed form that Douglas first accessed them. Beckett remained committed to the medium of television—he went on to produce several more pieces with the support of the Süddeutscher Rundfunk network in Stuttgart—but Douglas’s appreciation of Beckett’s teleplays was not widely shared, and they were rarely broadcast after their debut.

In 1983, having just completed his degree at the then-named Emily Carr College of Art, Douglas read another Beckett work, the 1979 novella Company. This story about a man lying on his back in the dark attempting to make sense of images and voices conjured from his past made such an impression on Douglas that he spent the following year, in his words, “reading Beckett ‘backward’ to his earliest writings, finding a very different artist from the one I had been taught to expect.” Douglas’s yearlong immersion in the works of Beckett resulted, according to curator Scott Watson, in all of Douglas’s installations from the early to mid-1980s “referring in a greater or lesser degree to the Beckettian ontology.” Douglas’s works from this period, Deux Devises: Breath and Mime (1983), Panoramic Rotunda (1985) and Overture (1986) among them, are noticeably concerned with Beckettian themes: the role that language, images and memory play in the constitution of the self, and the increasingly expanded function that technology performs in the calibration of lived experience.

Douglas’s project remains the only one of its kind—no other curator in the intervening 30 years has been daring enough to present Beckett’s moving-image pieces as a major independent exhibition.

Throughout his Beckett year, Douglas became ever more aware of the visionary quality of the older artist’s accomplishments in moving-image media. Frustrated by his inability to see the works he had only read, Douglas set out trying to locate copies of the films and videos. He travelled to the BBC in London and to the Beckett archives in Reading, and visited Paris, New York and Stuttgart. Hoping he would successfully locate the tapes, Douglas eventually applied for a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts and proposed an exhibition of Beckett’s teleplays to the Vancouver Art Gallery, ultimately receiving generous support from both institutions. Douglas was only 25 at the time, and this project would be his first—and only—solo curatorial project.

“Samuel Beckett: Teleplays” opened at the Vancouver Art Gallery on October 1, 1988. It resituated Beckett’s maligned teleplays as video art, and Beckett himself—still largely celebrated as a playwright—as a contemporary artist. The exhibition took the form of two television monitors on which eight of Beckett’s moving-image projects were played in a continuous loop. It toured to 19 different locations across Canada, North America, Australia and Europe. In the lead-up to the show, Douglas wrote to Beckett and spoke to him on the phone. Then 81, Beckett remained preoccupied with the possibilities of advancing audiovisual technologies and continued to contemplate the new forms into which his work might still evolve (one of his last pieces was a video version of his play What Where, produced in 1987). He was pleased by Douglas’s ambitious initiative to mount an exhibition of his teleplays in a gallery. “Best wishes for your project,” he wrote to Douglas on February 4, 1987, in one of a number of correspondences between them.

At the same moment he was curating and touring his Beckett exhibition, Douglas was conducting his own experiments in broadcast television art. His Television Spots (1987–88) and Monodramas (1991) aired on local television in Saskatoon, Ottawa, Toronto and Vancouver, interrupting the ordinary flow of broadcasting. Douglas’s short videos (ranging from 15 to 60 seconds) mimicked the conventional camera work of commercial television, but intentionally frustrated dramatic expectations by offering only fragments of an otherwise unexplained narrative. These Television Spots and Monodramas were inspired by Beckett’s teleworks, but they also participated in a broader tradition of broadcast video art that includes figures such as the German curator Gerry Schum and his pioneering Television Gallery. From these existing examples Douglas drew a strategy for producing and disseminating art outside the confines of the mainstream gallery system.

The prescient nature of Douglas’s “Samuel Beckett: Teleplays” and its contribution to the development of international video art has yet to be fully acknowledged. Douglas’s project remains the only one of its kind—no other curator in the intervening 30 years has been daring enough to present Beckett’s moving-image pieces as a major independent exhibition. Other artists currently working with film and video and referencing Beckett, such as Gerard Byrne and Duncan Campbell, testify to the importance of Douglas’s exhibition and the rare public access it provided. Following Douglas’s lead, Campbell has also sought out Beckett’s teleplays, a process that, he has observed, “felt like a pilgrimage.”

What is exceptional about Douglas’s “Samuel Beckett: Teleplays” is the bold and uncompromising manner in which the works were presented. Some three decades later and despite an increasing number of contemporary artists directly acknowledging his influence, Beckett remains affiliated with the stage in the public imagination. Yet in a time when short videos, including several of Beckett’s television works, circulate on platforms such as YouTube and UbuWeb, Douglas’s expanded vision of Beckett feels increasingly right—providing a different creative context than the one we have been conditioned to expect, and upholding the complexities and nuances of Beckett’s commitment to multimedia.

Samuel Beckett and actor Klaus Herm rehearse Beckett’s television play Geistertrio (Ghost Trio), 1977. © SWR/Hugo Jehle.

Samuel Beckett and actor Klaus Herm rehearse Beckett’s television play Geistertrio (Ghost Trio), 1977. © SWR/Hugo Jehle.