The 2018 Liverpool Biennial does a thing well that most biennials claim to do, but never seem to achieve: it brings local and international artists into a meaningful conversation with the local context. For this 10th anniversary edition, titled “Beautiful world, where are you?” director Sally Tallant enlisted veteran curator Kitty Scott, with whom she worked at Serpentine Galleries in London. Tallant, who has run the biennial since 2012, and Scott, who has put together important exhibitions for the Banff Centre and Documenta 13, and is currently Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, engaged 40 artists from 22 countries and rooted the exhibition in the community with residencies and artists projects.

“It is through arts and culture that we express our hopes and fears and articulate alternatives and new possible worlds,” Tallant said during the press opening last week. The invited artists were asked to “reflect on the question ‘Beautiful world, where are you?’ focusing on these pressing issues: inequality, conservation, extinction, education, resource extraction, Indigeneity, post-colonialism. Within its public spaces, galleries, museums and civic buildings the city of Liverpool provides the setting.”

A working-class city in the north west of England, that was at one time one of the most affluent cities in Britain, sustained by the cotton, tobacco, sugar and slavery industries, Liverpool experienced a sharp economic downturn in recent decades, making it a site rife with the contradictions, complications and possibilities of the present day.

The well-integrated urban spread of the partner venues asks visitors to move through different areas of the city, and in this way enter into local spaces that may not be art-related, but contain some aspect of Liverpool’s unique history and culture. You walk along the docks, past the Merseyside Maritime Museum, to arrive at Tate Liverpool, for instance. You go into the courtrooms and underground prison chambers of St. George’s Hall to see discreet film installations; you walk by the city’s massive Oratory to see a film projected in the interior of its stone abbey; you pass through a university courtyard to see special exhibitions; and venture to the historically Black Grandby neighbourhood to enter a collaborative garden installation. In this way, the biennial shapes and engages new audiences: not only just art-minded visitors, but also locals going about their everyday.

Unlike extravagant displays sometimes seen in other biennials, the works, as well as the way in which they are distributed among venues, allow for discreet, repeated and surprising encounters.

Standout examples of well-integrated projects include British artist Ryan Gander’s Time Moves Quickly, a collaboration with five local schoolchildren that yielded a public sculpture installation at Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. Likewise, French-Algerian artist Mohamed Bourouissa—along with a presentation of his 2013 film Horse Day, about the Black horse-riders of the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club in Baltimore—worked with a local community to build Resilience Garden, a permanent community garden built in partnership with students and teachers at the Kingsley Community School. Bouroussia worked closely with Bouriem Mohamed, a patient at the the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital, where, at one time, the psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon used gardening as a form of therapy. Together they designed the layout of the Liverpool community garden, later populated with a cross-section of plants that are connected to Britain, Algeria and the moving horticultural histories of colonialism. The garden is intended to remain in place, and be managed indefinitely by the local community.

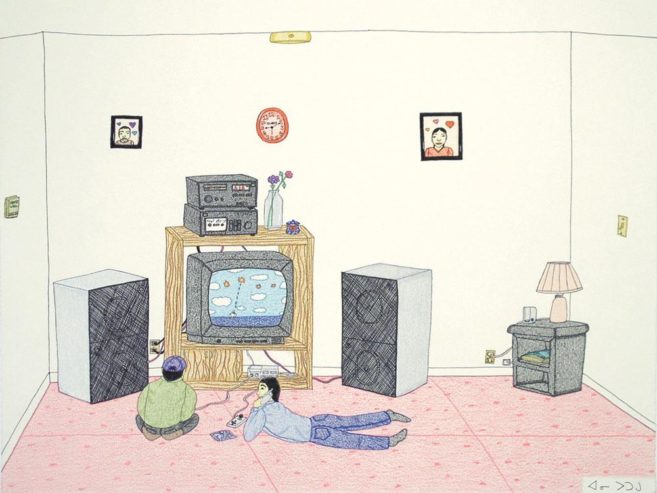

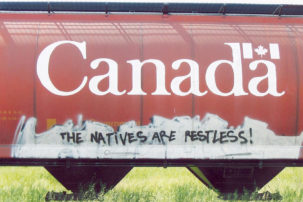

Scott also introduced several Canadian artists to the biennial. Brian Jungen, Duane Linklater, Annie Pootoogook and Joyce Wieland present drawing, film and sculptural works at Tate Liverpool. A large selection of Pootoogook’s pencil drawings, many familiar to Canadian audiences from her recent McMichael Canadian Art Collection exhibition “Cutting Ice,” present stunning, humourous and profound social commentary in colourful and poignant depictions of contemporary Inuit life. Also shown at the Tate was Joyce Weiland’s Rat life and diet in North America (1968), made during the height of the Vietnam War, depicting a political allegory told via the live-action adventure of a group of gerbils who escape the United States for organic farming in Canada.

At St. George’s Hall, a neoclassical law court and prison that dates back to the mid-19th century, Weiland’s work Sailboat (1967) was projected in a corridor over an underground bridge. Nearby was Jungen and Linklater’s film project, Modest livelihood (2012), which follows the artists on two hunts in Dana-zaa Territory in northern British Columbia. Mesmerizing in its banality, the silent, 50-minute film captivates the viewer with sustained, unspectacular scenes ambient with the expectation of the hunt. Jungen, Linklater and Weiland had works in several venues, as did many artists in the biennial. In this way, the organizers created subtle lateral networks of exhibition.

One recurring comment about the biennial—which boasts 53 per cent women artists participating—is that it is understated. This may or may not be a result of the exhibition’s feminist organizing, but it is experienced by the many paths for walking across the city to exhibition venues. Unlike extravagant displays sometimes seen in other biennials, the works, as well as the way in which they are distributed among venues, allow for discreet, repeated and surprising encounters that are neither planned nor ostentatious.

Abbas Akhavan, Variations on Ghost, 2017–18. Installation view at Bluecoat as part of the 2018 Liverpool Biennial. Photo: Mark McNulty.

Abbas Akhavan, Variations on Ghost, 2017–18. Installation view at Bluecoat as part of the 2018 Liverpool Biennial. Photo: Mark McNulty.

At Bluecoat, alongside installations of work by Ryan Gander, Melanie Smith, Suki Seokyeoung Kang, Silke Otto-Knapp and Shannon Ebner, is 2015 Sobey Art Award winner Abbas Akhavan’s Variations on a Ghost (2018). First shown in a different iteration at Museum Villa Stuck in Munich in 2017, for this installation Akhavan displaced seven-and-a-half tons of soil into the the gallery space and over ten days, carefully compressed it with water and built it into the shape of the feet of a fallen monument to reference the destruction of ancient sculptures by ISIS. Viewers can smell the earth as they enter the space. The work’s largeness in the smallness of the space allotted for display mirrors the ways cultural histories are often ravaged or cut down to accommodate ruling regimes. After the biennial, the soil for the sculpture will be donated to local gardens.

The Liverpool Biennial grounds its international conversations locally with a variety of projects, collaborations and significant partnerships. This is Shanghai is a collaboration that showcases works along Liverpool’s waterfront by emerging contemporary artists from its twin city in China. We Are Where We Are is the final exhibition of partnerships developed over three years between 11 artists from northern England with curators from New York. The John Moores Painting Prize shows works from this year’s edition of the 60-year old competition. The Bloomberg New Contemporaries is another highlight, shown at the Liverpool School of Art and Design and John Moores University; its an exhibition of surprising new work by recent graduates from art schools across the country chosen by guest selectors Benedict Drew, Katy Moran and Keith Piper.

Beyond those collaborations, many notable contributions can be seen throughout the biennial. For example the artist Taus Makhacheva, a qualified therapist, offers special sessions where visitors were invited to a sculptural facial treatment accompanied by a 30-minute autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) performance. Also at the Blackburn House with Makhacheva are three short films by Rehana Zaman, who worked with a cooperative of young Somali and Pakistani women over six months to build their own semi-fictional story about Liverpool’s marginalized histories.

Though most of the Canadian contributions are older works, already presented extensively in North America, it is significant that distinct Canadian conversations and art practices are being pulled into a global context for the biennial. “I run a feminist organization,” Tallant declared during a talk she gave with Scott earlier this spring at the AGO. “I describe what we do as being a situated curatorial practice,” she further explained. “We work in the city. We work with the people and talent and organizations in the city but we’re networked in our thinking and we operate both locally—so a local operation on the ground together with our communities and our artists—and at the same time we connect to a global context. And it’s our job to bring a local conversation to Liverpool.”