Following a national controversy about the deaccessioning of Marc Chagall’s Tour Eiffel, the work was returned to public view recently at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. There, following public petitions and call-in shows and behind-the-scenes board wranglings, it hangs on the second floor of the building, in the European Galleries, and will continue to do so until Winter 2019.

But many misunderstandings about deaccessioning and museum collections still remain both within and beyond Canada. Regarding Chagall, “the aftermath raised more questions” than it answered, says Lloyd DeWitt, chief curator at Virginia’s Chrysler Museum of Art. Formerly curator of European art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, where he oversaw a major deaccessioning effort, DeWitt is still curious about the role that the Department of Canadian Heritage might have played in the matter, and observes that “the role the Quebec government in restricting the sale and trade of cultural property [like the Jacques-Louis David] came as a surprise—anyone at Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board or the museum world would tell you that this was not normal procedure for Canada.”

If DeWitt’s vast expertise has left him with many questions, a largely uninformed public likely has many more. One of the main truths that did surface during the Chagall affair was how little most members of the Canadian public—and even those in the self-identified art public—know about deaccessioning. In the specialized art media, it is a term that jumps out from headlines, usually with negative connotations.

It’s time to look at some of the original and essential purposes of the deaccessioning process in museums, as well as look at the process by which it has become—in some cases—a suspect practice.

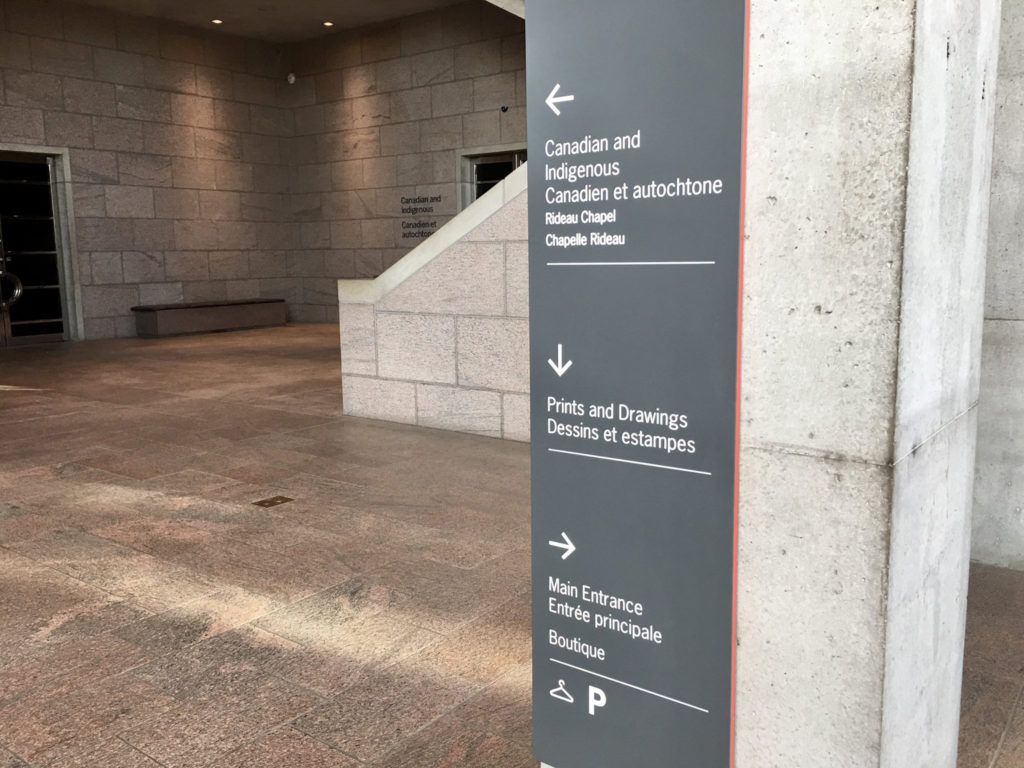

Signage at the National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Facebook.

Signage at the National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Facebook.