Experiences are more valuable than things, but what is an experience except a specific arrangement of things? A cumulative and tacit understanding of varied material aspects sensually absorbed, as well as culturally mediated?

In the sense of being aids or conduits to experience, every thing is a material, and therefore innately equal. We impose value—in the eye of the beholder, in the hand of the holder, in the mind of the maker—and things remain blissfully unaware of this. They may be the truest sadists, caring not for our pleasure, but absolutely foundational to our experience of it.

When I stopped making clothes I stopped making anything at all for a brief time. And while I don’t intrinsically miss anything about making clothes, I certainly was not able to leave behind the hands-on, material exploration that had always been a significant point of genesis in my artistic process.

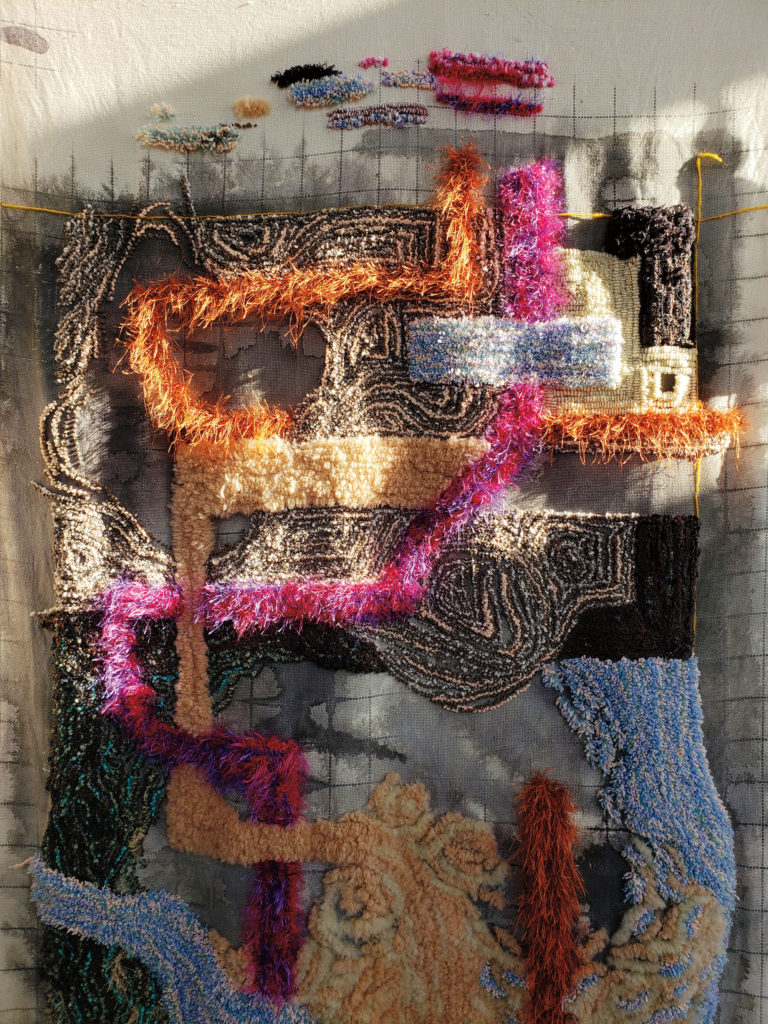

Seeking another way of approaching textiles, after clothes, I turned to a tufting gun, a mechanical yarn-drawing tool used in commercial carpet manufacture. The resulting works—extemporaneous, sculptural yarn paintings they could be called, perhaps, though “tapestry,” “piece-of-cloth” or “sampler” will also do—are made as much to be touched as to be looked at.

Photo: Jeremy Laing.

Photo: Jeremy Laing.

Photo: Jeremy Laing.

Photo: Jeremy Laing.