There is a clamouring to hold on to what we can. Fighting for the scraps left behind by our battle-worn parents, who, on the front lines as children, held onto every last morsel of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit they could—no matter the punishment, no matter the cost.

In the city, I’d gauge my comfort level with people when I’d catch myself almost letting myself in, turning the handle, half-opening the door before recoiling in my faux pas, closing it back again and then knocking. We never knock. The unexpected yet clichéd revelation of leaving home, with all the usual small-town angst of needing to get out, was that I found my inherent Inukness the farther away from home I wandered. It was the longing for the land and community that brought me back.

The divide of the culture clash is so entrenched that the laceration of colonialism’s rabid bite runs marrow-deep in our bones. How do we heal from such deeply inflicted wounds? Our country: a gaslighting, abusive boyfriend who makes laughably feeble attempts at reconciliation. We all know healing is up to us. There is a clamouring to hold on to what we can. Fighting for the scraps left behind by our battle-worn parents, who, on the front lines as children, held onto every last morsel of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit they could—no matter the punishment, no matter the cost.

We brand ourselves with uluit ubiquitous, we tattoo our faces, we reclaim things once taboo. We gather around cardboard with bloodied hands, palms facing upward in humble unconscious praise, tools at work in the meat as we converse and laugh in raucous bursts or silently savour every last bite, the nearly neon condiments proclaiming the inescapable collision like tiny billboards in the background. A clash of worlds so deeply woven, we lovingly embrace China Lily as a traditional condiment.

We sing our ancient songs, tell and retell our sacred stories and resurrect rituals long forgotten. We work to reclaim our mother tongues. For some, to hear any word spoken in English is like the echo of a schoolmaster’s whip cracking open the trauma of our displacement with every forced foreign syllable. We react, we scold. For some, we speak our languages awkwardly, but unashamed. At least we try. It is another way of staking our claim in this befuddled space. Each of us desperately and wondrously trying to hold on to what was, while moving forward into a space unknown. We must gather. We must speak. We must eat. We must partake.

Inuit principles are universal: no waste, use all you have, share what you are able to, and sometimes more. When stripped down by the sheer unapologetic force of nature, ego is subdued. It was a system built around survival. Everyone had a role, a specific skill set that instilled deeply personal and communal pride and value. This connectedness is what is carried down through millennia. Moving away from the idea that the old ways are precious yet primitive. We open our vision, seeing how vital the old ways are to our modern survival. We gather together to gain strength, to showcase skills, to tell stories, to celebrate, to laugh, to eat together. These are the spaces they inhabit. Wherever we find ourselves, each of us has our point of contact, where we are able to lean back into the embrace of our traditions without hesitation or discomfort. The place where questions of identity and belonging completely dissipate. The place where we hear them.

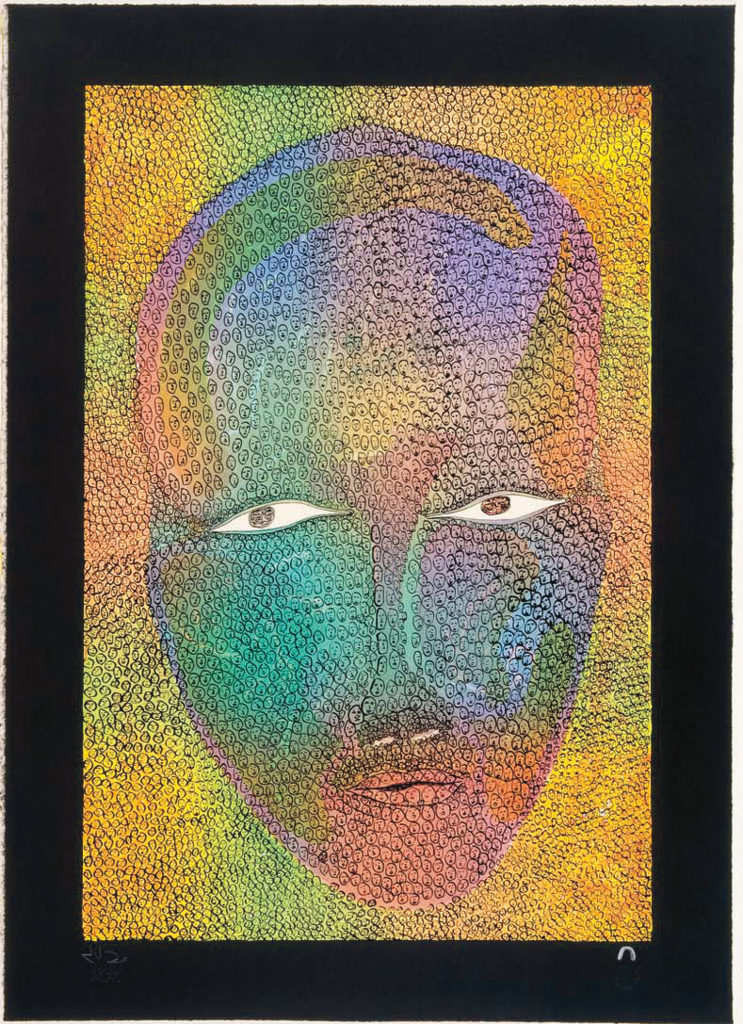

Jutai Toonoo, Not me anymore, 2010. Lithograph, 63.4 x 45.7 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada. Courtesy Dorset Fine Arts.

Jutai Toonoo, Not me anymore, 2010. Lithograph, 63.4 x 45.7 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada. Courtesy Dorset Fine Arts.