When the Raptors made the playoffs last spring, I watched along with the rest of the city. I’d never followed basketball before but found that I knew most of the rules because I grew up in a house where a game was always on in the background. This year, the NBA was one of the first high-profile leagues to suspend its season in response to the coronavirus pandemic, which made me nostalgic for the palpable fervour in the streets of Toronto during last year’s championship series. In lieu of the playoffs this year we have The Last Dance, a 10-episode docuseries directed by Jason Hehir, which follows the Chicago Bulls leading up to and during the 1997–98 NBA season. Co-produced by Netflix and ESPN, it was released two episodes at a time over the course of five weeks. As I made my way through the series, I realized that not only had I absorbed the rules of basketball, I had also absorbed its imagery.

Throughout the ’90s, the Bulls were the team to beat, thanks to an all-star lineup that included, at various overlapping junctures, Scottie Pippen, Dennis Rodman and Michael Jordan. By the ’97–’98 season, the future of the team was in doubt: many of their superstar players were entering the twilight of their careers and years of unaddressed tension with management threatened the unity of the franchise. Hehir constructs the documentary as a champions-to-underdogs story, interspersing behind-the-scenes footage of preseason training camps and locker-room pep talks with flashbacks from the last 40-odd years of the franchise. The series outlines the backstories of Pippen and Rodman, two formidable players in their own right, but just like the Bulls in their glory days, the spotlight shines brightest on Michael Jordan—still considered the greatest player of all time more than 15 years after his last professional game.

Jordan has always been in control of his image. An intuitive, almost superstitious awareness of his own brand combined with unparalleled athletic skill turned him into a household name. I was only a kindergartener during the ’97–’98 NBA season, by which time Jordan was everywhere: on cereal boxes, in commercials, on billboards and in the news. I watched Space Jam every weekend, tearing up during the movie’s climax when Michael returns to Earth after winning a game of basketball against a group of aliens, thereby thwarting their plan to destroy humanity. (Notably, the scene is soundtracked by I Believe I Can Fly, a song that will forever be haunted by the nefarious legacy of its singer.) Even as a kid, I knew Michael Jordan was a “good” man. Not a father figure exactly, more like someone who could’ve been friends with my dad, the kind of guy who’d be genuinely curious when he asked me what I was up to in school. This has consistently been part of Jordan’s brand strategy, one which persists throughout Hehir’s characterization: he seems like a guy you could have a beer with, and who would also be a role model for your son. Jordan is a moral paragon: no drugs, no partying, only good old-fashioned work ethic. There are rumours of a gambling addiction, but Jordan dismisses the claims as slanderous hearsay. If Jordan was aggressive during practice, it’s only because he wanted his teammates to play to the best of their ability; if he holds grudges, some dating back more than 30 years, it’s only because he cares so deeply about the sport. Hehir stages Jordan’s talking-head interviews inside the all-white pool-side den of his mansion in Jupiter, Florida, a cigar and a tequila glass on the side table, as though the camera, and by extension the audience, has been invited to play Friday night poker. Two episodes in, I had the epiphany that Michael Jordan had been my childhood hero, if not my first crush.

The oversized suits, the mix of streetwear and business attire, jewellery that looks unassuming but reveals its flash upon closer inspection: my entire wardrobe is an unconscious homage to Michael Jordan.

My unwitting idolization continued into adulthood. In one of the more juicy reels of behind-the-scenes footage, Jordan is shown boarding a plane with the Bulls’ in early 1998. The camera zooms out to capture him on the tarmac, wearing a grey hoodie under a long black coat, baggy black pants and a black beret. Watching this moment unfold, I had the uncanny experience of realizing I was wearing almost the exact same thing. The oversized suits, the mix of streetwear and business attire, jewellery that looks unassuming but reveals its flash upon closer inspection: my entire wardrobe is an unconscious homage to Michael Jordan.

Jordan’s most important contribution to style, and culture by extension, is the Air Jordan, a shoe which arguably led to the acceptance and subsequent co-optation of streetwear into high fashion. Hehir takes us on a detour during episode five to discuss the genesis of Jordan’s famous endorsement deal. As the story goes, Jordan didn’t want anything to do with Nike when they approached him for sponsorship in the mid-80s. Nike was known then as a track shoe company with no cultural cache, and NBA superstars Magic Johnson and Larry Bird had sponsorship deals with Converse. But Jordan’s mother insisted he attend Nike’s pitch meeting, and the rest is history. Air Jordans quickly became the most popular shoe on the market, particularly within Black communities—director Spike Lee and rapper Nas are among the notable celebrities who venerate Jordans in the series. Air Jordans sold through aspirational affinity; to quote Nas, “you needed that shoe to be like him.”

Jordan Casteel, MegaStarBrand's Louie and A-Thug, 2017. Oil on canvas, 198.12 x 228.6 cm. Courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York.

Jordan Casteel, Jahi, 2019. Oil on canvas, 228.6 x 198.12cm. Courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York.

Jordan’s reluctant acceptance of a lucrative business deal has had a significant ripple effect on visual culture. Consider Kehinde Wiley, Jordan Casteel and Brian Jungen, three contemporary artists exalted in their professions to Jordan-like prestige, who each use Air Jordans to signify different aspects of status. Wiley inserts contemporary Black figures into recreations of European portraiture to disrupt (or perhaps replicate) the canon of white Old Masters; his subjects are most commonly seen in either Timberlands or Nikes. By placing these brands into the visual lexicon of European portraiture, Wiley elevates their status to royal adornment, like the powdered wigs and petticoats of French Rococo. Many subjects in Casteel’s paintings can be found sporting Jordans as well, but the sneakers become quotidian in the context of her intimate, usually domestic stagings. If Wiley’s Air Jordans are the ultimate status symbol, Casteel’s Jordans could belong to anyone. Jungen’s Prototypes for New Understanding (1998–2005) is a series of Northwest Coast masks created from ripping apart and splicing together pairs of Jordans, manipulating their material construction to suggest parallels between the commercial and art-historical fetishization of Black and Indigenous aesthetics. Jungen began the series in 1998, the same year around which The Last Dance centres, when Jordan’s global fame was at its peak. Try to imagine Jungen’s Prototypes made out of Converse.

Brian Jungen, Prototype for New Understanding #13 (detail), 2003. Nike air jordans, human hair, 64 x 24 x 39 cm. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver

Brian Jungen, Intimidation Mask, 2018. Nike air jordans, copper, 69 x 91 x 48 cm. Photo: Rachel Topham Photography. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver.

Brian Jungen, Prototype for New Understanding #10, 2001. Nike air jordans, human hair, 28 x 36 x 58 cm. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver

Brian Jungen, Prototype for New Understanding #2, 1998. Nike air jordans, human hair, 49 x 21 x 3 cm. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver

Brian Jungen, Persuasion Mask, 2018. Nike air jordans, copper, 109 x 79 x 38 cm. Photo: Rachel Topham Photography. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver.

Brian Jungen, Prototype for New Understanding #23, 2005. Nike air jordans, human hair, 47 x 52 x 15 cm. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver

These are just three examples of the sneaker’s semiotic fluidity. A pair of Jordans may be au courant to some, nostalgic to others; they may represent the (Black) American dream and its unattainability, or the similarly unattainable goals of (Black) masculinity. Air Jordans might be the appropriation of Black aesthetics, or the reclamation of those aesthetics. Air Jordans could be considered a Black capitalist success story, but they could also be evidence of corporate exploitation, the targeting of racialized markets, outsourced and unregulated labour, environmentally destructive manufacturing processes. They may signify all of the above, or none of it. I’ve always wanted a pair, but I can’t bring myself to buy them.

In another tangent of The Last Dance, the series reveals that Jordan has managed throughout his career to conveniently sidestep any public declaration of political allegiance, another testament to the self-awareness of his branding: he doesn’t want to piss off the sponsors. When he covers the Reebok logo on his tracksuit at the 1992 Summer Olympics so as not to appear disloyal to Nike, he creates a controversy reminiscent of Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising the Black Power fist on the Olympic podium 24 years prior—but Jordan’s gesture was cynical in comparison. He respects the picket line of the mid-’90s baseball strike but refuses to endorse Harvey Gantt, the Black Democratic candidate running for senate in Jordan’s home state of North Carolina. He’s famously quoted saying, “Republicans buy sneakers too.” He shrugs off the statement as an “off-the-cuff” joke, an explanation that does little to clarify his convictions. To be fair, Jordan has publicly donated to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the Institute for Community-Police Relations, but nothing close to a significant percentage of his substantial net worth. Through an ambiguous portrayal of the icon’s apolitical tendencies, Hehir lets Jordan off the hook. It’s too bad Jordan didn’t use his influence to support Black activist initiatives, the documentary suggests, but politics is more Muhammad Ali’s thing.

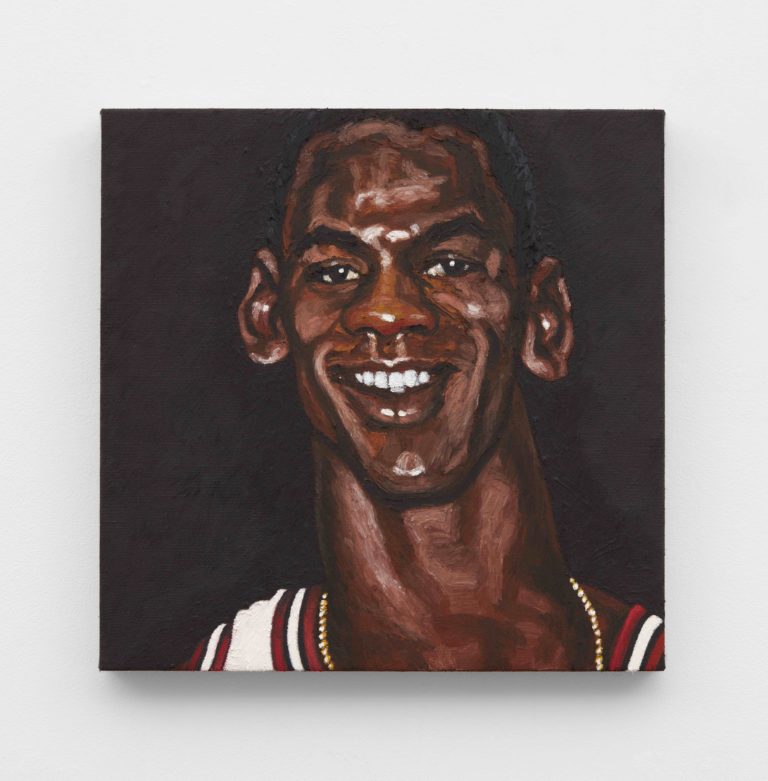

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Jordan, 2018. Photo: Matthew Kroening. Courtesy the artist.

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Jordan, 2018. Photo: Matthew Kroening. Courtesy the artist.

I’m reminded of another Jordan-inspired artwork, a portrait by American painter Nathaniel Mary Quinn. Simply titled Jordan (2018), the painting is more conventional than Quinn’s usual portraits, which distort the faces of his subjects in a manner evocative of Francis Bacon. Painted with the reverence of fan art, Jordan shows the NBA champion from the shoulders up against a black background, the red and white of his Bulls jersey peeking up from the bottom of the canvas. Quinn has cited Jordan as an inspiration to him growing up in the South Side of Chicago, a childhood admiration that’s evident in the cartoon-like exaggeration of Jordan’s jawline and neck, with the white gleam in his eyes echoing the white of his handsome smile. Here, Jordan is a superhero.

The Last Dance doesn’t challenge the myth of Michael Jordan, nor did I expect it to. Too many stakeholders depend on the maintenance of that myth either directly or indirectly, including Nike, the NBA and any other business Jordan has a longstanding partnership with, not to mention ESPN, who produced the series. The Last Dance is visually slick, a well-crafted piece of storytelling, but, much like its hero, commercial interests prevent it from taking a stance beyond the status quo. If some audiences find this authorized story of Herculean triumph too depoliticized to stomach, they can find alternative versions in the work of artists who have borrowed from Jordan’s visual lexicon. These artists use the iconography of Jordan to tell less straightforward stories of race, power and cultural memory. I’m not prepared to abandon my childhood hero, but I temper my admiration with these alternative ways of understanding him. It reminds me that individual virtuosity is too easily subsumed by capitalism and white supremacy to be considered a structural threat on its own. If Michael Jordan stands for nothing, then his shoes can stand for anything. This vacuum leaves behind only images, ubiquitous and ripe to be read.

Brian Jungen, Prototype for New Understanding #8(detail), 1999. Nike air jordans, 58 x 19 x 38 cm. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver

Brian Jungen, Prototype for New Understanding #8(detail), 1999. Nike air jordans, 58 x 19 x 38 cm. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver