I’ve been painting, drawing and writing for as long as I can remember. I come from a small village in Bas-Saint-Laurent, Quebec, where I was raised in a poor and abusive environment, and was also bullied at school. I first created art from a place of survival, trauma, emotions. My imposter syndrome appeared long before I entered the literary world or academia. I was studying arts at a rural college in Bas-Saint-Laurent. My teachers were all about abstract art. I felt like an imposter for not being into it. I was treated like an outsider because they did not like my figurative paintings. At that time, I was inspired by sci-fi and fantasy, and much more interested in H.R. Giger than Jean-Paul Riopelle. My art was deemed less worthy, especially since at that time I didn’t care about impressing anyone or acquiring cultural capital. This was my first experience of gatekeeping in the arts world.

Gatekeeping is the act of controlling or limiting access to an institution. Its consequences are the formation of an elite, and the safekeeping of knowledge and positions in their hands. I would argue that most of the time it is not overt, it is covert. It is in discourses, norms, expectations and behaviours that people co-opt to become, and to stay, part of this social group.

Coming from a lower socio-economic class, I see gatekeeping as not only an access and integration problem, but also as a major source of imposter syndrome. The feeling is of a persistent, nagging inability to believe that my success or place is deserved or legitimate. I feel the weight of even more as a published poet who hasn’t studied literature, but instead history.

I came to appreciate abstract art when I moved to Montreal to complete my undergrad degree at the Université du Québec à Montréal. Was it the fact that I grew older or that I moved to the city? Was it because I began to long for cultural and social capital to be accepted by my peers? It’s probably all of these, and much more. But I didn’t study art. I’ve decided to pursue history. I was always interested in this topic, and my imposter syndrome was already too strong, so I felt like I didn’t have my place in the art world. I was told I was not good enough to make a living as an artist, and as a writer. In my family, and where I came from, art was not something that was valued as a career, or at all. Only an elite could make a living out of their art. It was for snobs. And, anyways, it was for exceptional people. Was I not exceptional enough?

I stopped painting and drawing during my undergrad and graduate studies, but I didn’t, and couldn’t, stop writing. When I showed my writing to people studying literature, I was often told my work was not refined enough, not good enough. Despite this, secretly, I wanted to write.

Meanwhile, I was also feeling like an imposter in academia. I was critical about its symbolic violence. The culture of exhaustion, with 80-hour weeks, and people almost laughing at how exhausted they were, but somehow normalizing it. The constant need for networking. The anxiety-producing scholarship hunt. Working for free on articles and symposiums just to get your name on a paper. The lack of intimacy with friends and family resulting from all of this. It warranted me some gaslighting by my PhD supervisor: If I couldn’t endure it, he said, it was because I didn’t want it bad enough. Maybe. Or maybe I just couldn’t, with my mental health. With everything I was witnessing and didn’t agree to. I ended up dropping out of my PhD in 2015. It broke my heart to do so, but I also knew it was the right thing for me to do.

“The context is telling you that the things you’re looking at are art. So whoever decides what’s in the museum decides what good taste is, what’s beautiful, and what’s valuable…. You learn taste according to the social class of your upbringing. And with taste comes all this adult baggage: snobbery and pretense and conceit.” —Natalie Wynn, Contrapoints | Opulence (2019)

Two things helped me articulate the way I felt in academia, and in the literary world.

First, I discovered the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu coined/redefined the terms “capital” (as being economic, social, cultural and symbolic) and “symbolic violence.” The notion of cultural capital is of greater interest here. Cultural capital is the knowledge, taste, skills, clothing, credentials and so on that someone acquires when being part of a given social class. Symbolic violence is an implicit power dynamic in which a social group imposes its norms on a subordinate group. Symbolic violence is not just being unable to speak the proper language of an institution, of an elite, with its codes, norms, etc., but also being coerced into accepting the rules as-is. It’s easy to imagine how someone who didn’t inherit cultural capital and who is put through the symbolic violence inherent to gatekeeping then develops imposter syndrome.

Second, I started watching Contrapoints, a channel where ex-philosophy student and trans Youtuber Natalie Wynn explores topics like gender, politics and philosophy. In her video essays Why I Quit Academia and Opulence, Wynn completely nailed how I felt and showed me not only that was I not alone, and these feelings not easily dismissed; she also showed me that there are critiques of these institutions out there, critiques by academics, artists and even people who were part of this elite. Her work validated my critical thinking about the elite’s symbolic violence, as well as my feelings.

When I published my first poetry book in 2016, I felt and was treated like an imposter for writing in vernacular, and especially in joual, the working class dialect of francophone Québec. For many, this dialect, historically associated with lower classes and statuses, is considered vulgar, and less valid in literature than “true” French. Again, as when I was painting and drawing, I was writing with intention, emotion and experience as my main material, rather than language. I wrote about my abusive childhood, about mental health, suicide and trauma. My style was deemed to be confessional writing, like Sylvia Plath, and many young writers are part of this stylistic school.

One literary critic made an unnecessarily harsh review of my book that I felt crossed a line. I was completely crushed and ashamed. But I decided to publicly reply to them on Filles Missiles, a feminist literary blog, in an essay called “You Can’t Sit With Us.” This started a small, or not so small, controversy in our small literary scene, but also discussions about the role and ethics of critics, about this particular style of writing and its worth. I was not the only one thinking this particular critic had gone too far. Other people defended what the critic said, but I still felt like these discussions (about me) did not include me. To these people I did not possess the cultural capital to be included; I did not have any knowledge of this world, the people, the norms, the academic knowledge. I felt like gatekeeping was trying to keep me out of my own story.

Writing, and being published, made me realize how writing was truly my medium as an artist: How much it meant to me. And how little this fact meant to others. I felt like I would never recover from this twinned reality. It got to the point where I thought about ending my life. It was not the first time that had occurred to me—but writing meant so much to me and I was being, yet again, confronted with my origins and my lack of cultural and social capital.

I still feel like an imposter. Every day I’m trying to write, and to read the classics I “should” have read, as well as keeping up with new releases. The gap between what I read and what my peers read feels like this poem from Quebecois poet Jean-Guy Forget:

je découvre ducharme et kundera

au cégep avant de me faire dire

ce sont des bonnes lectures pour le secondaire

à l’avenir je tairai

mon rattrapage

i discover ducharme and kundera

at cégep before being told

these are good high school readings

in the future I will not tell about

my catching up

My writing has transformed. I still write with intention, emotions and experience. But I no longer write in joual. I no longer feel like it’s my voice. I also no longer consider myself a confessional writer. I work with language rather than emotions as a primary tool. This is the direction my writing took as I’ve learned to work with language to serve my intent.

And while I’m afraid some may think of it as more “institutional,” I write what I love. As I’m writing new poetry, I’m afraid some of the people who related to my first book of poetry—Shrapnels—will think I’m now a parvenue. I now write like the very people who criticized me, and whom I used to criticize (and still do). I don’t write to please anyone else.

As I continue publishing and have new projects on the way, I humbly hope that my experiences and writings have helped to open a dialogue about topics like gatekeeping and imposter syndrome, as well as the role and ethics of critics. I hope my journey can help future young writers and artists from rural areas and poor upbringings who are told that their work “just doesn’t fit”—that it helps them know they can take up the space they want, be part of these discussions, and tear down the gates.

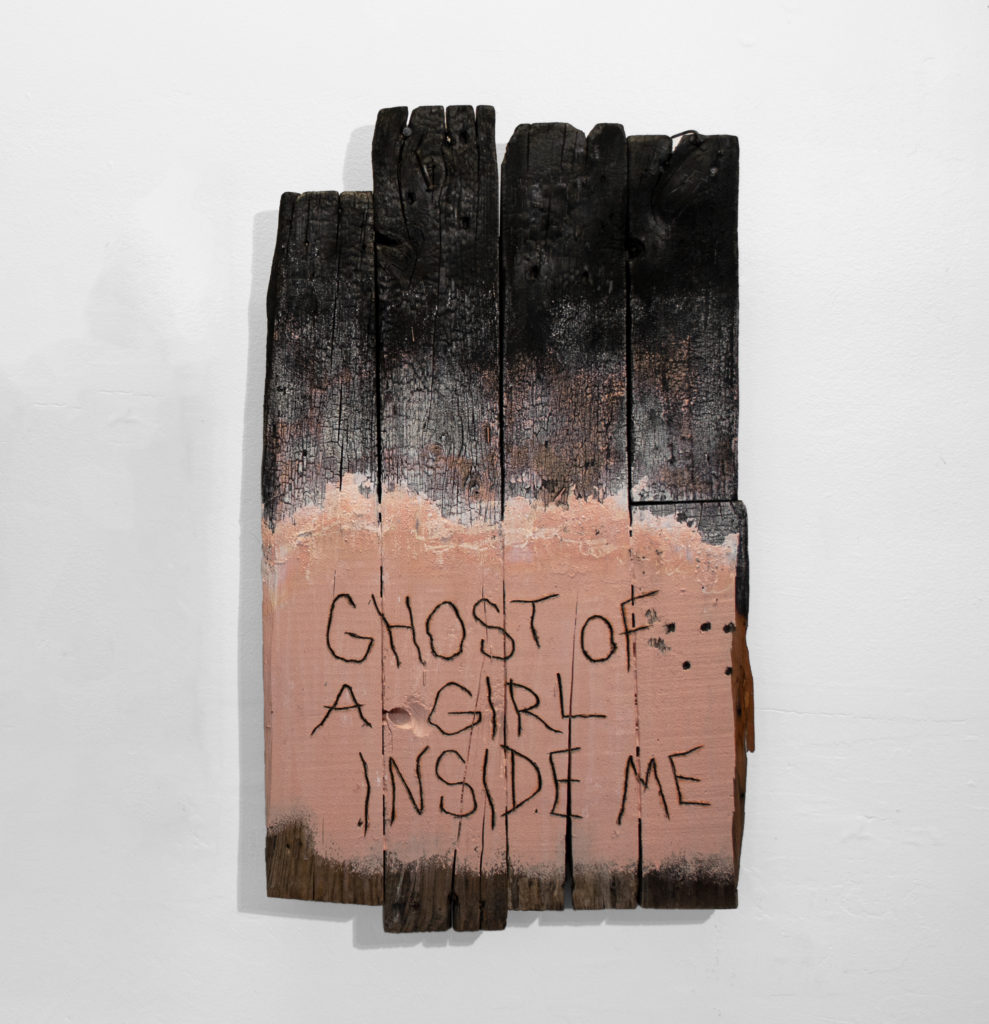

Courtesy of Severine Vae, Ghost of a Girl, 2020.

Courtesy of Severine Vae, Ghost of a Girl, 2020.