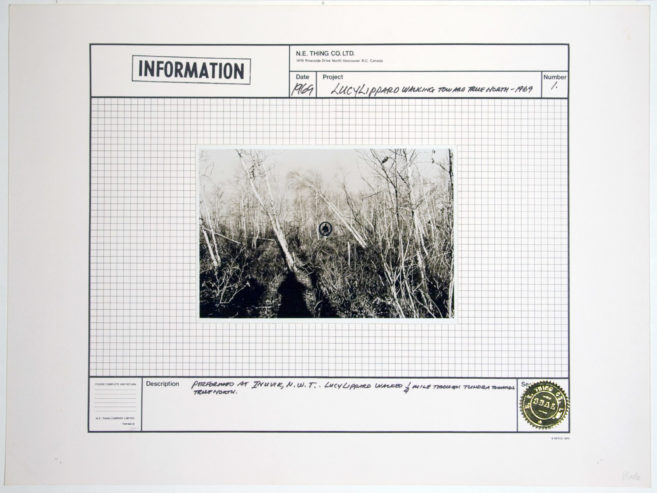

Nearly 50 years ago, in early September 1969, a group of conceptual artists gathered on Sir Winston Churchill Square in downtown Edmonton to make a series of site-specific works. Canadian artists Iain and Ingrid (then Elaine) Baxter of the N.E. Thing Company (NETCo) were joined by New York-based artists Dan Graham, Les Levine, Robert Morris, Dennis Oppenheim and John Van Saun. They had assembled to participate in “Place and Process,” an exhibition organized by independent curator Willoughby Sharp and Edmonton Art Gallery Director Bill Kirby. (Later that month Kirby, along with artists Lawrence Weiner, Harry Savage, NETCo, writer Virgil Hammock and critic Lucy Lippard, visited Inuvik, in the Northwest Territories, for what Lippard describes as a kind of postscript to the exhibition, “a naively colonialist art-scouting trip.”) Edmonton might seem like an unlikely location for the execution of the fleeting, environmental artwork typically associated, in the 1960s, with artistic centres like New York or the grand landscapes of the American West. But, as a site, the city appealed to these artists because of its geographical remoteness and state of rapid urban development and, such as it was, inspired a series of unusual and amusing artworks.

The concept of “site”—in particular the dialectical relationship between “site” (a real place out in the world) and “non-site” (a physical piece of the site that stands in for it, relocated to a gallery or museum)—was a crucial concern for contemporary artists in 1969. Some sites were more exotic and difficult to access, while others were examples of new, modern landscapes—such as the “suburban banal.” Often the “site” chosen for a work would have either an inherent significance, to be extracted, or would function as a void, to be filled by an artist’s action upon it.

Still from Place and Process, 1969, 30:01, Robert Fiore, Evander Schley and Willoughby Sharp (Great Balls of Fire Inc., New York), produced in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name at the Edmonton Art Gallery, September 24–October 26, 1969. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Alberta.

Still from Place and Process, 1969, 30:01, Robert Fiore, Evander Schley and Willoughby Sharp (Great Balls of Fire Inc., New York), produced in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name at the Edmonton Art Gallery, September 24–October 26, 1969. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Alberta.

In 1969, Edmonton lay somewhere between these two understandings of site— appealing to the artists for both its physical distance from New York and its relative anonymity. (In phone conversations with the artists before they arrived in Edmonton, Kirby described it as “1600 miles north of Denver.”) It was also a city in transition. Following the start of large-scale commercial oil production from Alberta’s Athabasca oil sands in 1968, Edmonton and its surroundings came to symbolize accelerated progress, shifting from an economy dominated by agriculture to one of resource extraction. Urban infrastructure was expanding on such a scale that, in the October 1969 issue of artscanada, critic Norman Yates described “a skyline that seems to change monthly.” For the visiting artists, Edmonton was a site of unknown and untapped potential, and some locals sensed its latent possibility too. Edmonton was quickly beginning to resemble the big, rich city it would become, and the physical growth, influx of cash and connection to an international network created energy that some—such as Kirby—felt could be steered toward generating a unique and organic art scene.

The Edmonton Art Gallery was also in a moment of transition, as it moved from a cramped, private residence to a purpose-built building the same year. For the opening of the new building, Kirby wanted an appropriately avant-garde exhibition to complement the EAG’s Brutalist architecture, and he collaborated with New York-based Sharp to envision “Place and Process”—an exhibition of “outdoor sculptural projects” that existed in two parts. The first was a program of process works made in and around Edmonton, and the second was a display of documentation of artworks made both in the city and elsewhere. Appropriate for a city in transition, “Place and Process” characterized Edmonton as both site and non-site. For the artists who travelled there from New York, it was a new and remote location where they could make site-specific works, while the Edmonton Art Gallery became a non-site through the installation of documentation of works made in places as distant as the Arctic and Kenya. “Place and Process” introduced international conceptual art practices to local Edmonton artists and audiences and advertised Edmonton to audiences of contemporary art further afield.

Edmonton locals, such as the art critic Virgil Hammock, were enthusiastic but unconvinced. In his review of the exhibition for the Edmonton Journal Hammock wrote: “Newness and originality are only two factors in art and neither of them are necessarily related to quality.” The exhibition was probably more successful at capturing the attention of audiences elsewhere. In the months following the visit, New Yorkers encountered Edmonton through the documentation of “Place and Process” published in Artforum and the artist journal Avalanche, and at “Information,” a survey of conceptual art curated by Kynaston McShine at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

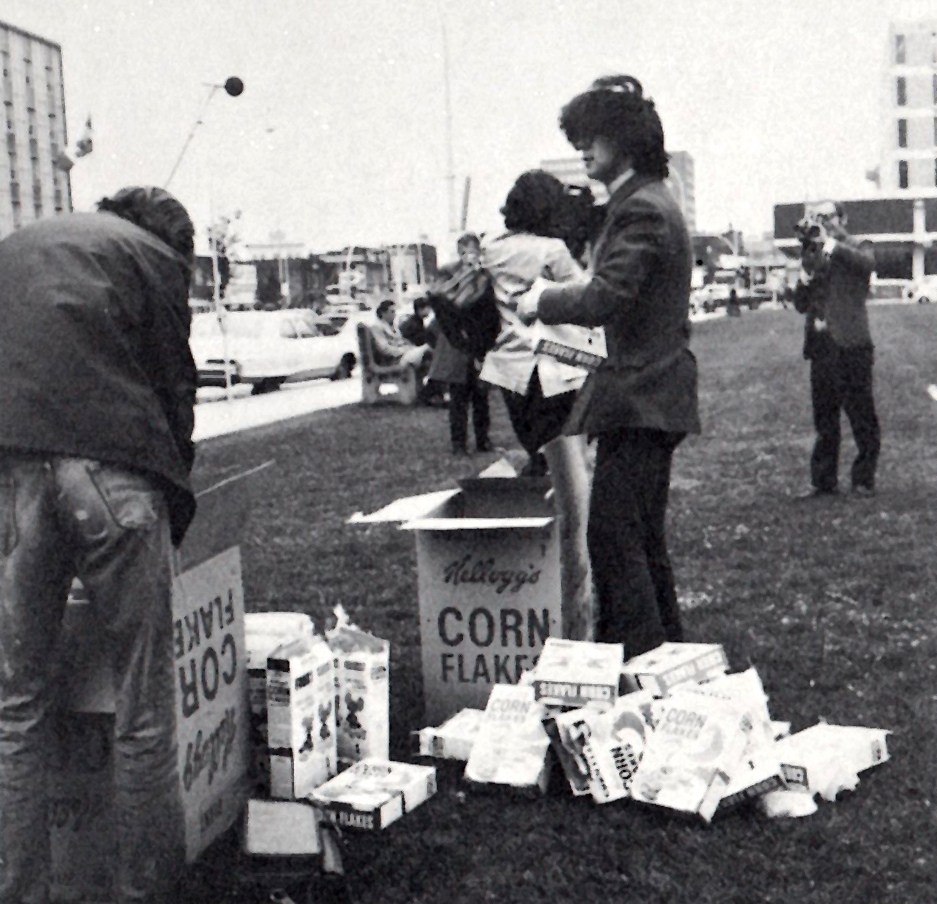

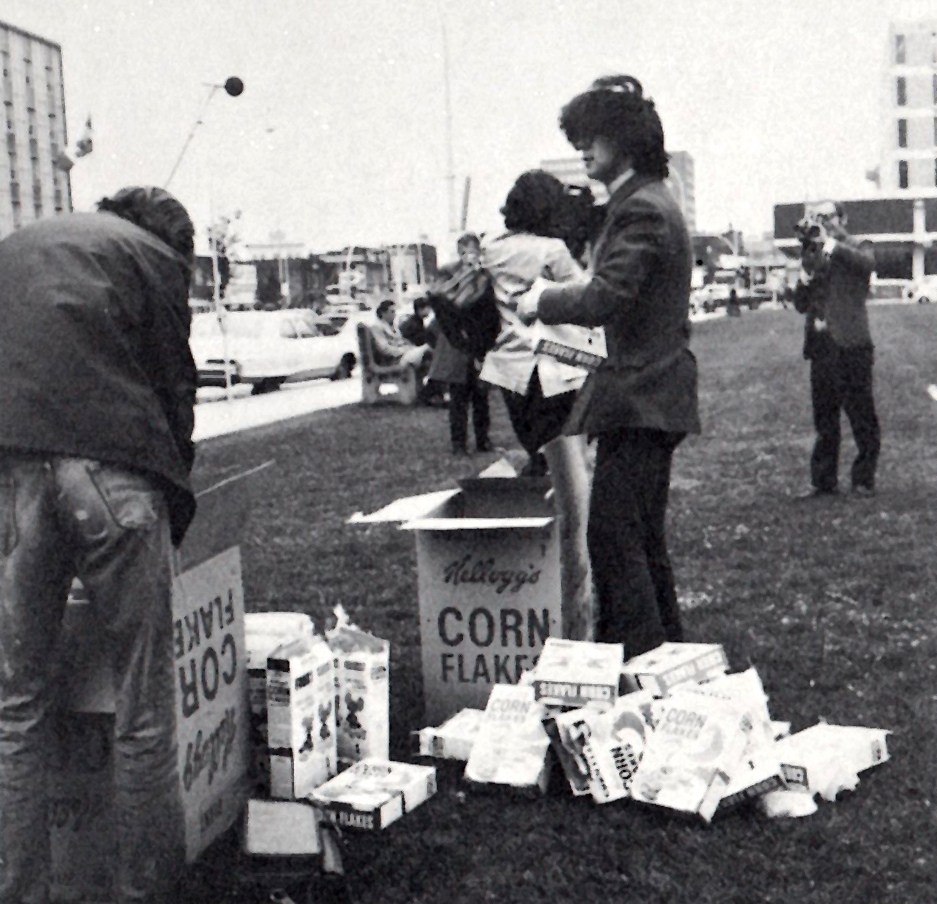

Les Levine, Cornflakes, 1969. Photo: Willoughby Sharp

Les Levine, Cornflakes, 1969. Photo: Les Levine

Still from Place and Process, 1969, showing Edmonton media interviewing Les Levine. 30:01, Robert Fiore, Evander Schley and Willoughby Sharp (Great Balls of Fire Inc., New York), produced in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name at the Edmonton Art Gallery, September 24–October 26, 1969. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Alberta.

Still from Place and Process, 1969, 30:01, Robert Fiore, Evander Schley and Willoughby Sharp (Great Balls of Fire Inc., New York), produced in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name at the Edmonton Art Gallery, September 24–October 26, 1969. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Alberta.

But what unfolded in Edmonton was quite different from what had been proposed. Only one of the six works was executed as planned, and only one took place in the square, while the rest were spread out across the city and into the surrounding farmland. Les Levine’s Cornflakes saw the artist and a group of participants sprinkle the contents of 250 jumbo-size boxes of Corn Flakes cereal over the grass of the central square, creating an absurd performance site specific both for its mediocre outcome (the cereal in the grass, resembling autumn leaves, was aesthetically underwhelming) and agricultural undertones (the aim of the work was to let nature re-digest its own materials). John Van Saun’s Flour Drop was a similar but more spectacular interaction between food and the environment: the artist had bags of flour pitched at him, which he hit with a baseball bat, temporarily engulfing himself in white clouds.

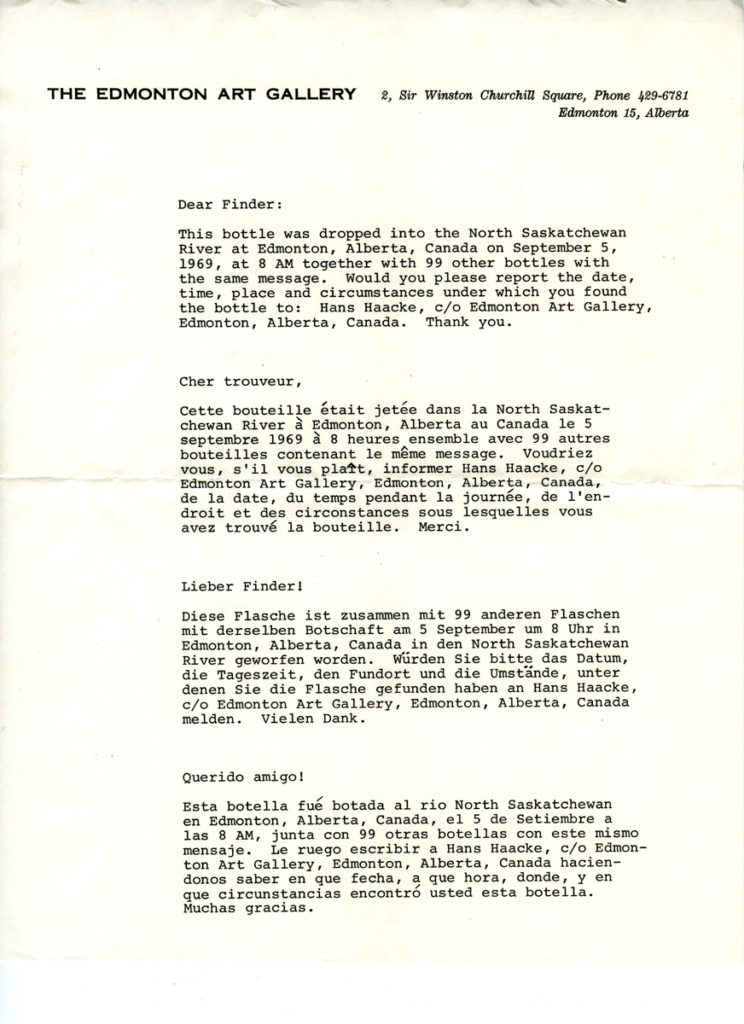

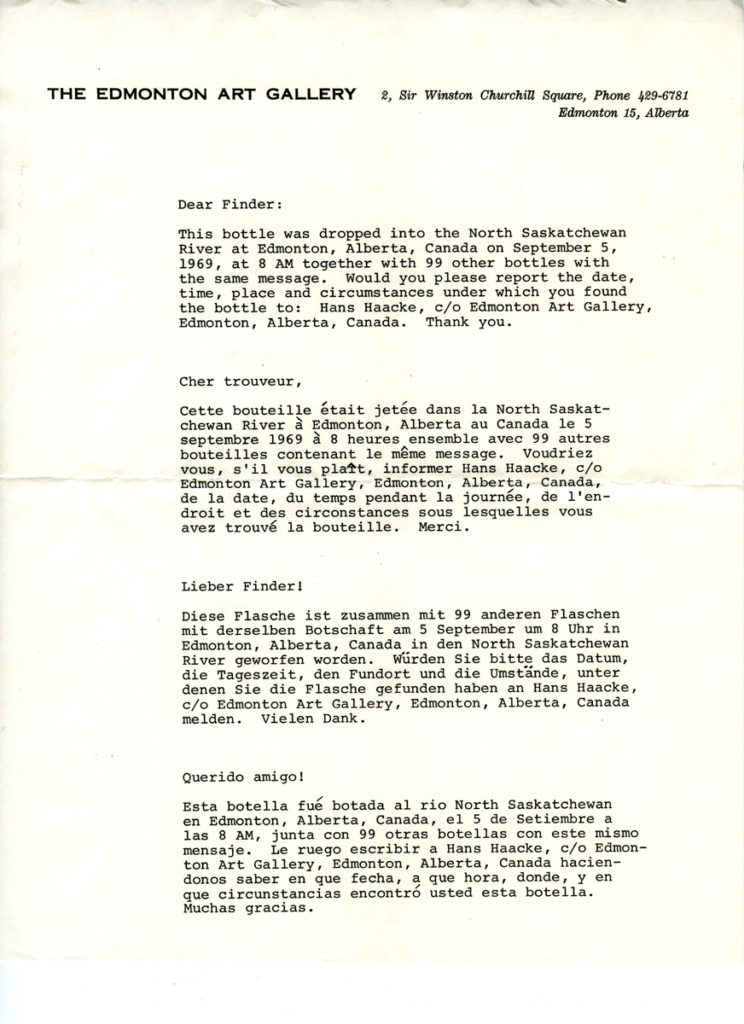

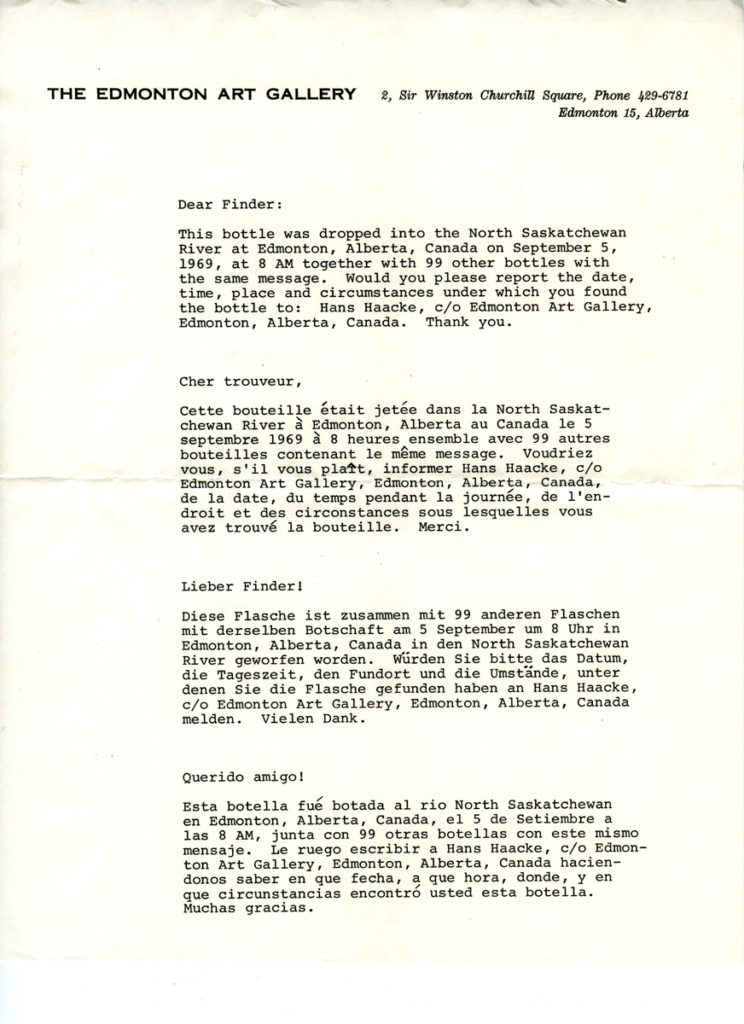

Dan Graham executed Hans Haacke’s untitled work by throwing 100 bottles from the Fifth Street Bridge into the North Saskatchewan River. The bottles each contained a message written in English, French, Spanish and German, asking the finder to write to Haacke at the Edmonton Art Gallery with the time, place, and circumstances in which the bottle was found. The work responded to the newly global Edmonton, now connected by the natural resources flowing through it, and referenced the city’s geographical remoteness by proposing to measure the distance between the city and unknown places downstream.

![Hans Haacke [executed by Dan Graham], <em>Untitled [letter that was placed inside 100 plastic bottles]</em>, 1969. Collection: Bill Kirby](https://canadianart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PlaceProcess08-744x1024.jpg)

Hans Haacke [executed by Dan Graham], Untitled [letter that was placed inside 100 plastic bottles], 1969. Collection: Bill Kirby

![N.E. Thing Co., <em>Nothing Project</em> [displayed on steps of Edmonton Art Gallery], 1969. Photo: Willoughby Sharp](https://canadianart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PlaceProcess08-744x1024.jpg)

N.E. Thing Co., Nothing Project [displayed on steps of Edmonton Art Gallery], 1969. Photo: Willoughby Sharp

Robert Morris, Pace and Process, 1969. Photo: Bob Fiore

Iain Baxter and Dennis Oppenheim in Edmonton for Place and Process, 1969. Photo: Bill Kirby

Dennis Oppenheim and Robert Morris also marked and measured space in their contributions to the exhibition. Oppenheim executed Condensed 220 Yard Dash by attempting to run through the mud in a vacant lot behind the gallery and then making plaster casts of his footprints, later displayed in a stack in the museum. The work established a clear relationship between the exterior site and the interior non-site, with the plaster casts standing in for the muddy lot and serving as a record of the artist’s movement through it. Morris similarly marked outdoor space by movement with his work, Pace and Process, for which he rode a horse back and forth along a straight line at the G Bar E Ranch about 25 miles east of Edmonton, engaging with Alberta’s ranch culture as a way to respond to the specificities of Edmonton as site.

It is somewhat ironic that, due to the city’s cultural marginality, its brief moment of international art-world centrality has been largely overlooked.

NETCo were unable to execute their grazing project that would have used sheep to mark an X in the grass on the central square, and instead carried out a controversial piece titled Nothing Project: in keeping with their penchant for exaggerated institutional critique, the artists poked fun at the fashion for site-specificity by retreating to their Edmonton hotel room for a designated period during their visit, refusing to execute a work. Nothing Project was thus a protest against the demands placed on artists to make work on location, demands that necessitated travel, by invoking the significance of another site—the one they left in Vancouver—and suggesting they were just as capable of producing good art at home as they were anywhere else.

Instead of producing an exhibition catalogue, Sharp hired New York filmmakers Robert Fiore and Evander Schley to document the works with a film that was later included in “Information.” The film consistently engages Edmonton as site, showing how the artists’ commitment to recording the reality of the place went beyond the execution of the works, affecting how they were documented and subsequently received elsewhere. Fiore and Schley paid particular attention to the environments in which the works took place, the reactions of the live audiences and the ways in which the artists were approached by the local media. There is a self-conscious layering of documentation as footage of Flour Drop is overlaid with audio from CKUA, a local Edmonton radio station, discussing a new system for grain marketing. The filmmakers accessed the roof of a building adjacent to the central square, making use of one of the new high-rise buildings to film Cornflakes amid the expanding skyline. What emerges is a portrait of a place in process, a city latent with possibility.

Although Edmonton didn’t have a clear civic identity for the visiting artists to engage with in 1969, the possibility inherent in the city made it an appropriate place for the execution of site-specific work. Kirby had hoped “Place and Process” would establish a connection between Edmonton and an international conceptual art scene but it was not to be, and the exhibition is both anomalous in the city’s cultural history, and the first chapter in the alternative history of a city that could have been. It is somewhat ironic that, due to the city’s cultural marginality, its brief moment of international art-world centrality has been largely overlooked. A further irony is that “Place and Process” took place at a moment when the province’s priorities had shifted away from supporting culture and toward promoting urban development, as indicated by the closing of the Calgary Allied Arts Centre the same year. Now, although Edmonton is open for international business and oil money is used to support the arts, the city-as-site is steeped in the significance of the industry that runs it, and lacks the uncertainty and possibility that momentarily characterized it.

Still from Place and Process, 1969, showing Les Levine's Cornflakes, 30:01mins, Robert Fiore, Evander Schley and Willoughby Sharp (Great Balls of Fire Inc., New York), produced in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name at the Edmonton Art Gallery, September 24–October 26, 1969. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Alberta.

Still from Place and Process, 1969, showing Les Levine's Cornflakes, 30:01mins, Robert Fiore, Evander Schley and Willoughby Sharp (Great Balls of Fire Inc., New York), produced in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name at the Edmonton Art Gallery, September 24–October 26, 1969. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Alberta.