My Aunt Reesa is Samsara eau de parfum and Belmont cigarettes. She’s also a husky voice, and a warm, throaty laugh. A kiss on each cheek. A hug that squeezes, swaying from side to side, eyes closed, inhaling, “mmmmmmm.” Then, an invitation to eat, and a question: “What can I get you to drink?” But all this follows. First, here is Reesa: Samsara and smokes.

Loss of smell is one of the weirder symptoms of this pandemic. There are other losses too. I miss the art gallery where I work. If I try to remember what the gallery smells like, it was wet paint, and only sometimes, if anything. Still trying to be a good participant in the communities I belong to, I’m looking at art online. I wonder how much is lost through this mode of spectatorship. Visual art tends to privilege sight more than other senses. And sound, I suppose. Galleries smell pretty sterile in the first place. Have you noticed how everything you read during a pandemic has this newly uncanny veneer of crystal clear resonance? “As our reliance upon heavily ocular centric technologies evolve, and our daily interactions become more deeply immersed in remote, fractured, often-virtual experience, our reliance upon and relationship with our senses devolve,” artist Nina Leo wrote in her 2012 essay “The Politics of Smell.”

Nostalgia presents itself through scent—tugging and pulling us into memory’s imagistic order.

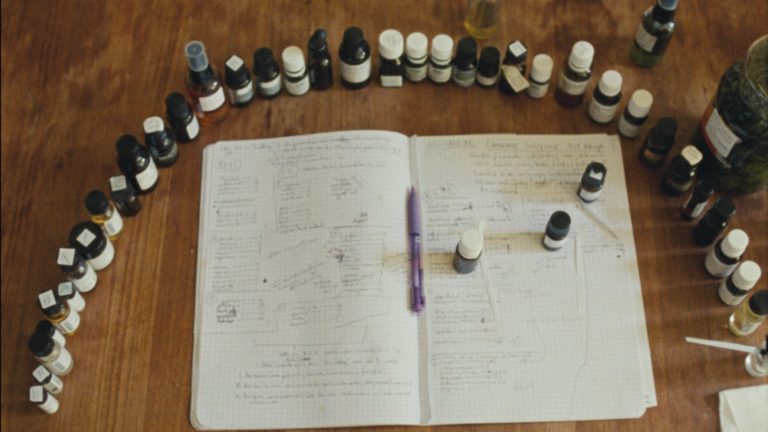

Leo and her collaborator, the poet and artist Moez Surani, have been engaged in an ongoing project, Heresies (2018–), which attempts to bottle a scent that evokes the tension between nostalgia and childhood trauma into vials of perfume. Collaborating with professional perfumers who grew up in war-torn or politically compromised cities—sites that have been historicized and, in turn, mythologized as harbourers of collective trauma—Leo and Surani task these perfumers with producing a scent representative of their childhoods. “Can one have a joyous childhood in Hiroshima? And how’s the swimming in Waco?” Leo and Surani ask in an artist statement. My Hiroshima (2018), created by olfactory designer Kayo Yoneda, is citrusy and bright. It’s made with notes of yuzu, grapefruit, rose and patchouli. My Waco (2018), designed by perfumer Joel Wilson, is rather woody and warm, made with coumarin, vanilla and cedarwood. When exhibited at Onsite Gallery in Toronto and New Zero Art Space in Yangon, each scent was presented in glass bottles on white shelves inside rounded, pod-like walls. Visitors entered this insular space and leaned in close to each bottle to sample the fragrance within. The gesture of intimacy in this presentation creates a moment of identification with each scent’s designer. Perhaps you are meeting My Hiroshima with a textbook understanding of what Hiroshima is, but leaning forward for a whiff, you smell what Kayo Yoneda presumably once smelled, and maybe once felt. Here, that which is embodied and ambivalent grounds the mythic site of trauma, and brings it back to its senses.

Joel Wilson, My Waco, 2018, from Nina Leo and Moez Surani's Heresies. Installation view, "The Sunshine Eaters," Onsite Gallery, Toronto. Photo Credit: Yuula Benivolski.

Kayo Yoneda, My Hiroshima, 2018, from Nina Leo and Moez Surani's Heresies. Installation view, "The Sunshine Eaters," Onsite Gallery, Toronto. Photo Credit: Yuula Benivolski.

Inhaling these scents, one feels capable of bypassing language, and arriving directly in the false comfort of memory’s imagistic order: My Waco and My Hiroshima smell nice. But a whiff only lasts a moment. After all, surely it’s not all sunshine and roses in Hiroshima, or in Waco, or in Barcelona or Baghdad—the latter being cities for which Heresies scents have also been developed, and will be presented in Leo and Surani’s exhibition “Yesterday Today Tomorrow” at YYZ Artists’ Outlet this month. As audiences and critics, we are often alert to visual art’s dubious frameworks, to the socio-economic matrix an art object folds into, sometimes intentionally as critique, or accidentally as a commodity. But because scent invites interior rather than social exploration, it may foreclose such considerations. Nostalgia and sensuality, however, are not innocent, and have historically been weaponized, often for racist ends.

If smell can, affectively, take us home, then smell also has a turn in forming our presumptions of strangers. Consider our seemingly benign taste for comfort foods. “These smells that we draw in can subconsciously evoke responses that are deeply emotional. They can trigger feelings of comfort, yet equally quickly set off a kind of squeamish disgust,” writes Leo. As anyone who was ever ridiculed for the aroma of their open lunchbox knows, there can be racism inherent in children’s experience of perceived bad smells. Something insidious forms in a child’s cultural understanding, which presents itself wholesomely enough as a soft spot for one’s family’s cooking. Food represents the feeling of home, and later on, its smells and tastes take us back home, while an intolerance of, or distaste for, a stranger’s home can form in tandem. Nostalgia is not neutral. This becomes obvious when considering any one of the slew of successful political campaigns that appeal to nostalgia, and the intolerance for others that is harboured within this good feeling.

I hug my aunt, inhale, and I’m instantly enveloped in Samsara’s familiar, handsome musk. When you look up Samsara,which is manufactured by the French cosmetics house Guerlain, you’ll find a list of adjectives: “Woody Oriental. Harmonious, spellbinding, embracing.” But what exactly am I embracing? Reesa or Guerlain? The aroma of home, or the fragrance’s legacy? If you lean in and smell My Hiroshima or My Waco, you get a sense of what the world must feel like for Kayo Yoneda or Joel Wilson. When I lean in and smell Samsara, it’s the world of Guerlain.

Samsara was launched in 1989 by Jean-Paul Guerlain, the great-great-grandson of the company’s founder, Pierre-François Pascal Guerlain, and the last so-called master perfumer of the Guerlain patriarchy. The company cut ties with Jean-Paul in 2010 for racist remarks he made about his inspiration for Samsara. With Jean-Paul’s racist comments, and ensuing public protests and related trial in which he was found guilty, Guerlain’s proudly branded old-worldly legacy as a perceived family business was destroyed. This notion of a perfume dynasty reeks of European colonialism, which reveals its hand in the comparatively covert racism in the perfume’s mythology. Apparently, Samsara smells “Woody Oriental, Harmonious, spellbinding, embracing.” Read aloud, this word association game—levelling a word as weighty and dated as “Oriential” to mean something equivalent to “spellbinding”—sounds like it’s meant to hypnotize. The name Samsara itself, derived from the Sanskrit saṁsāra, which can mean “wandering” or “world,” refers to a concept of reincarnation central to some Asian and South Asian religions. So this fetishistic, orientalizing sentiment endows the fragrance with a weird sense of poetic justice, as the perfume, which in one culture means rebirth, in another represents the death of the Guerlain dynasty.

Kashina, July 6 - July 13 2020, posts from Instagram/@illicium.verum.

Kashina, September 27 - October 4 2020, posts from Instagram/@illicium.verum.

Kashina, October 10 - October 16 2020, posts from Instagram/@illicium.verum.

In the spirit of such dramatic ad copy typical to the perfume industry, although more dank, experimental writer Kashina has an ongoing scent journal documenting her perfume collection. Her running archive illicium.verum.nova appears on Instagram and is collected in the book East of Borneo (2020). Samsara, writes Kashina in a 2018 review, “Reduced me in five seconds to slavering homage. Now I know what a lowly cur I am. It’s so splendid, it should be carried on a palanquin and have the adoring populace throw rose petals and ticker-tape at it.”

Kashina’s reviews tend towards the fleshy, epicurean and ornate. They often read as imagistic, personal and associative. Like poetry. Or like scent itself. Do scent and poetry, then, operate in the same realm? Do they speak the same language? According to Nina Leo, smell exists outside of language altogether. “Intellectually elusive and emotionally potent, smell, more than any other sense…has the ability to elicit feelings that are intensely visceral,” writes Leo, citing scent psychologist Avery Gilbert, who says that smell can conjure memories we don’t even “remember remembering.” The twin concepts of sense-memory and nostalgia are often discussed as particular to smell. Nostalgia presents itself through scent—tugging and pulling us into memory’s imagistic order—and asks to be treated with misty-eyed reverence, to be accepted uncritically, that is, without articulated thought. But trauma also functions like sense-memory, hibernating outside language and evading cognition.

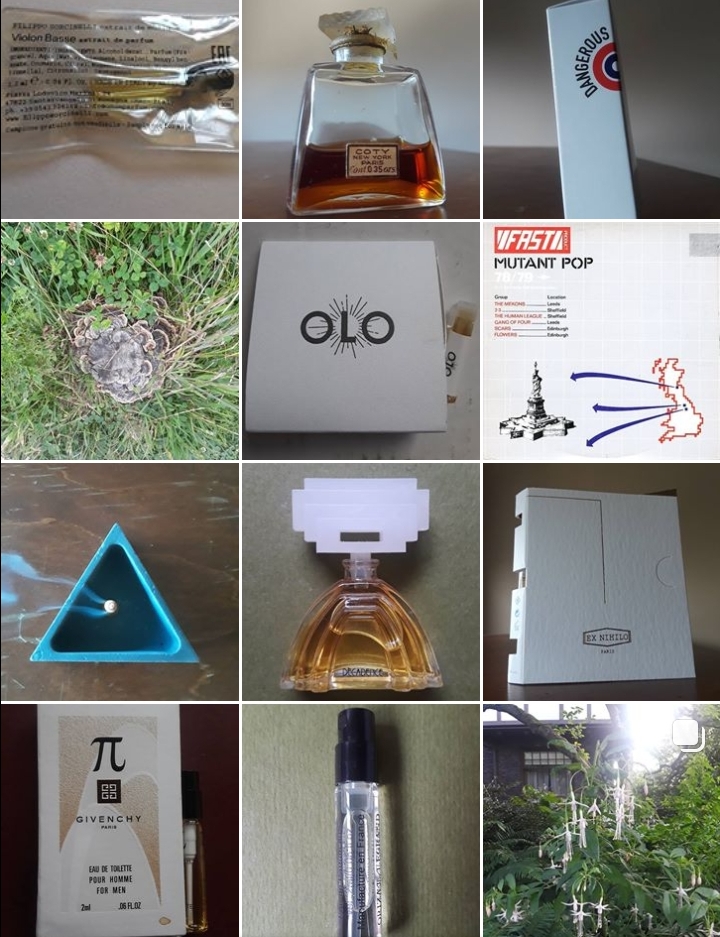

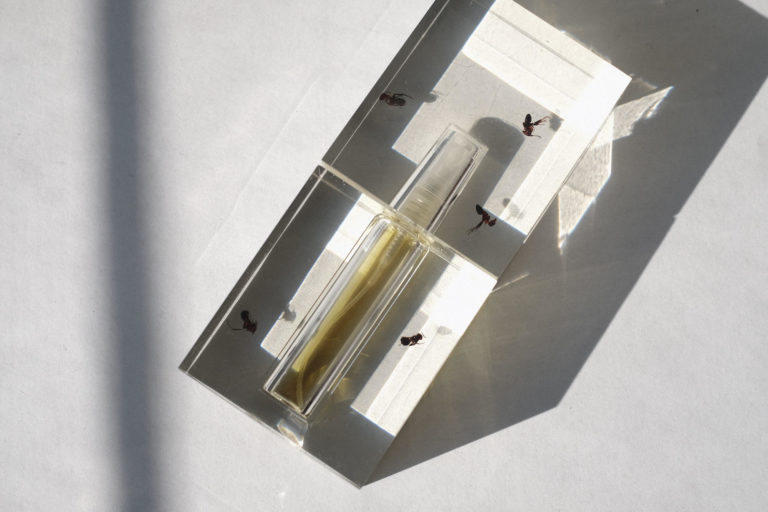

Anicka Yi, Radical Hopelessness, 2019. Resin, plastic, metal, wasps, eau de parfum. 12.7 x 5.2 x 2.54 cm. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery.

Anicka Yi, Radical Hopelessness, 2019. Resin, plastic, metal, wasps, eau de parfum. 12.7 x 5.2 x 2.54 cm. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery.

The year before last, experimental artist Anicka Yi debued Biography Fragrance (2019), a trio of perfumes, two of which are inspired by women from history. Shigenobu Twilight is based on Fusako Shigenobu, who lead the Japanese Red Army in the 1970s, and Radical Hopelessness is based on the Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut. Beyond Skin, another perfume from the collection, imagines the smell of an artificial intelligence that “holds the individual and collective history of every woman in a single, composite scent.” It’s made with notes of seaweed and suede. Biography, like the Heresies fragrances, draws on scent’s ability to summon the past, elevating the individual to the universal by suggesting that an intimate experience of sense-memory can upload onto a collective history. But Beyond Skin intimates a sort of ego death driven by a robot, and it speaks to the contradiction Leo articulated about scent as a mediating technology and a virtual technology, one that brings us together while it isolates and individuates.

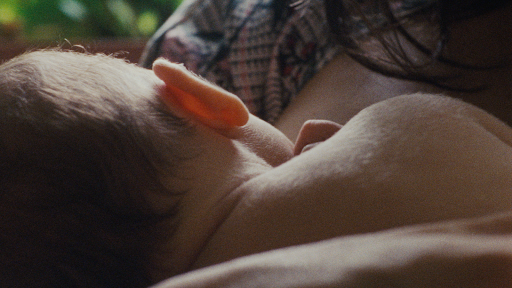

The cyclicality of birth and death as conjured by perfume is alluded to again in Vancouver filmmaker Kathleen Hepburn’s NFB documentary short Perfumed Dreaming (2020). Hepburn and her sister, painter and perfume designer Megan Hepburn, discuss smell as they grieve the death of their mother and meditate on the birth of Megan’s child. Over clips of a pregnant Megan anticipating her child and of the new baby in its mother’s arms, the sisters take turns voicing remembrances about the smell of their mother, and wondering about the similarities between Megan’s abstract painting and perfume-making. Painting offers a way to mourn her mother, Megan suggests, because it communicates through emotion. Scent, she says, does the same. Displaying images of Megan’s baby and telling stories of their mother, Kathleen uses cinema to mirror the intuitive response of a baby to its mother’s scent. The grown-up sisters use smell to grieve their loss. Smells and memories linger. Like conjuring a ghost, when you are familiar with someone’s smell, you might find that person anywhere you encounter their scent. “She is that scent,” Megan says. Unlike Heresies or Biography, which require your presence to smell and conjure the past, Perfumed Dreaming, as a video short, asks you not to smell, but to instead imagine you are smelling.

Perfumed Dreaming premiered online in April 2020, when COVID-19 had most cities in lockdown. “Here as never before, the media responsible for connecting us so effectively to one another also inherently prescribes physical and psychological estrangement,” Leo writes about our increased presence online. “And at the same time that our technologies distance us from sentient experience, they enable us to more effectively dupe the senses—creating fully fabricated images, sounds, smells and tastes.” I watch Perfumed Dreaming from bed. It was recommended to me by an article about artwork to consume when you can’t go to galleries.

Kathleen Hepburn, Perfumed Dreaming (still), 2020. Courtesy National Film Board.

Kathleen Hepburn, Perfumed Dreaming (still), 2020. Courtesy National Film Board.

Kathleen Hepburn, Perfumed Dreaming (still), 2019. Film, 5 minutes, 22 seconds. Courtesy the artist and the National Film Board.

Kathleen Hepburn, Perfumed Dreaming (still), 2019. Film, 5 minutes, 22 seconds. Courtesy the artist and the National Film Board.

As we are required to retreat inward, our mistrust of strangers is even stronger. The arc of COVID began for many with isolation and bottled-up emotions, and progressed to mass protests and public calls for social justice. Perfume is an elegant mask for our obsession with sanitization, our desire for escapism, and our fear of the other. Uncovering scent’s mystique, we follow a similar arc from the interiority of isolation (emotional or physical) to external action based on political consciousness. In Toronto, when people first started fearing COVID but before the city had shut down, I heard that a lot of people were avoiding Chinatown. For some, racism is the subconscious suggestion that a schoolmate’s food is smelly, that a Chinese restaurant is unclean, that there’s a direct contagion link from one country to a neighborhood in another. Eugenicism and genocide are frequently called ethnic cleansing. Sanitation and cleanliness are loaded concepts, already embedded with racist histories. Some of the first large public gatherings since city lockdowns were Black Lives Matter protests, a mass, collective response to deaths caused by police brutality. COVID presents itself as a monolithic public health crisis, superseding all other social issues—novel coronavirus is recent and (at least in terms of its basic replication biology) indiscriminate, and very much the opposite of police brutality, which is discriminatory and nothing new. Here, there’s a reckoning between the value of public health and the value of fighting racism, as if public health refers to only one public, as if life is a right that belongs to only one community.

Let’s say I’m overreacting, that a major pandemic had nothing to do with the civil rights protests that followed its onset, or that Samsara’s racist history has nothing to do with my sentimental attachment to it. Told differently, the story of Samsara is a love story. It’s said that Jean-Paul Guerlain actually created the scent four years prior to releasing it. In an attempt to flirt, he made a fragrance for a woman based on her favourite smells, jasmine and sandalwood. She wore it everywhere she went, and would get stopped on the streets and asked what she was wearing. While the perfume industry has us obsessed with that which is lovely, sanitized, whitewashed and romanticized, at the end of the day: scent smells. Brides used to hold bouquets of flowers to hide their B.O. Now we hold flowers because they’re romantic. We manufacture good smells to mask the bad smells, but that just means there’s a lot of bad smells. Samsara evokes a history of racism, also of jasmine. Perfume and the ever-growing sanitization industry encourage a buying into the masquerade that our hands are clean, while its underlying pathologies are bottled up and locked down until, when agitated, they come to the fore. But when you smell Samsara, it smells like flowers.

Kashina, Guerlain–Samsara, 2018. Photo: Instagram/@illicium.verum.

Kashina, Guerlain–Samsara, 2018. Photo: Instagram/@illicium.verum.