The last time I saw Richard was in Berlin, in 2016. It was a small evening gathering, at a mutual friend’s apartment in Schöneberg, where he was staying for the weeks of his visit; he had moved to Montreal by then (I think), and was no longer living in Berlin (I still am), but he talked with great hope of his long-term plan to spend a few months here every year. What became of those plans, I never knew.

When I first moved to Berlin from Toronto, in 2013, Richard was among the first to greet me. We met at a café in Kreuzberg, and I remember so distinctly how much lighter he was: his generous laugh was easier, his smile broader, his posture, his voice, his conversation all absent the hangnail edges of what I thought of as his characteristic demeanour. There was much about Berlin that suited him. The relaxed sexuality of the city allowed him not only to feel unambiguously desired and (more) at ease with his body, but also gave him rich fodder for lurid, gossipy storytelling (one of his favourite pastimes). The city’s literary and artistic culture recognized him immediately and unproblematically as a writer and a critic and a video artist. The (in)famous Northeastern German directness, brusqueness and total lack of social pretence, I think, charmed Richard the most. Here at long last was a place where politesse and etiquette and the virtues of the WASPish economy of appropriateness and restraint were not simply frowned upon, but recognized as false, dissembling and dishonest. The watchdog of social nicety was no longer prowling him.

The first time I saw Richard was in Toronto, in 2005. I could have sworn I encountered him and his work earlier than that, but an essay I wrote to accompany a project of his states otherwise. I had already become aware of his name, via his gloriously vituperative art reviews in Lola magazine. And in 2005, I was in the audience of an Inside/Out festival screening of short films and videos, my faith in queer art sinking one short film at a time, when Richard’s Hate appeared onscreen. The camera panned down his naked body as his voiceover enumerated a series of spiky, passive aggressive and hilarious apologies for all his perceived deficiencies and inadequacies. I laughed audibly, and immediately recognized a kindred spirit.

The first time I actually met Richard was in Toronto, though I can’t recall for the life of me exactly when, or how. It must have been through Andrew Harwood, at one of his openings at Zsa Zsa Gallery. We got on like a great gay house on fire. I was still ill at ease in Toronto, knowing few people and unable to sync myself to the social codes of gallery openings; I would have attenuated superficial chats with people I barely knew, always feeling like they were looking over my shoulder for someone more important to talk to. Not so with Richard. We didn’t chat; we conversed. He always had time for good conversation. Our mutual impatience with the glib pretensions of cocktail-party etiquette opened a beautiful commonality between us, and we immediately became the two fags in the corner, cackling joyously, clutching our cheap red wine and putting the room to rights.

I once wrote of Richard that we got along so well because we hated the same things. What did I mean? Certainly Richard was irked by many things, all of which became the ammunition for his keen volleys of bon mots (either written or conversational). But the things he hated and suspected the most, I think, were institutions. Particularly the intangible institutions of masculinity, beauty, class, taste, snobbery, genteelness, discretion, manners: the web of constraining traps that form the edifice of so-called polite society. These institutions that celebrate and reify the contained, measured, unobtrusive body abused him as they abuse so many of us; they forced him, as they force the rest of us, to perform his outrageousness and excessiveness as an entertainment for those who could dance untroubled along the strands.

But Richard was no victim, and so he used this hatred as the driving force of all his work: videos, criticism, poetry, fiction. His keenly felt outsider-ship provided the perfect perch from which he could observe and feel, and then, crucially, dive in, roll around and create. Whatever his form, whatever his subject, he was always neck-deep in it. He was no good at detachment and dispassion, and moreover, he knew them to be fabrications—illusory and useless and boring, a refuge of the bland and the cowardly. Liberated from this, he created without fear. This fundamental and constant refusal of distance gives all his work its pungency, intelligence, fun and beauty. He never made “cool” anything. In his videos, performances, fiction, poetry, you come right up against his inadequacy, his shame, his fear, his lust, his yearning, his tenderness, his passions. His criticism is likewise passionate, whether he was doling out praise or condemnation. Whatever he performed, whatever he spoke of, whether you agreed with him or not, his voice was always direct. And anyone who knows anything about the act of creation knows what a Herculean task it is to be direct. Richard was a ballerina of directness, his words pirouetting on point, dancing across the page with a graceful simplicity that belied the muscle of his craft.

And what did Richard love? There is a common misconception, especially in Nice Genteel Canada, that to be a critic is simply to be hateful (not so in Europe, which still has an active critical discourse, especially around the arts—another thing that delighted Richard about being in Berlin, I think). Richard had one of the most generous palates I’ve ever known. He loved the skillful, the well-crafted, the considered, the intelligent; he also loved the amateur, the haphazard, the untrained, the messy, the voluble. To say that Richard loved and championed the underdog is a maudlin inaccuracy. He loved things that were made well and honestly, and he knew of a certainty that the makers are all too frequently left uncelebrated by the institutions of culture and their gatekeepers. He was indifferent to and contemptuous of received tastes and therefore relied solely on his own bighearted barometers.

Richard loved to meet people, especially the earnest, the engaged, the unvarnished. He loved storytellers and raconteurs and gossips. He relished a good, juicy story. He loved weird kids doing weird things in their own weird ways. And he loved to introduce all these people to one another. Sometimes I think Richard’s favourite thing to do was to make social introductions. It visibly gave him immense pleasure, and I think it was his way of growing into the role of a queer elder. He wanted to create continuities of kinship among the likeminded; the tighter the cat’s cradle of funny misfits, the better. Certainly I benefitted from it; I remember going to parties at his house on Rusholme Road in Toronto, and it taking ages to get from the front door to the kitchen to the living room, because he needed to make sure that I knew every soul in every room.

And Richard was inexhaustibly generous with his support. I think he must have written something about every project I’ve ever done (adulatory, of course—but with Richard, you know that he is incapable of lying in print). He gave me my first major newspaper review, he suggested me for projects and exhibitions, he championed my writing, and I know he has done just as much for others. In this, he was among a small crowd of glaring exceptions to the conspiratorial zero-sum-game mentality of the Canadian art world. He knew intimately of the desperate need for a diverse, populous world of earnest, engaged artists. He knew that there was enough space for everyone, and the more of us there were, the better.

Richard was cantankerous and sarcastic and prickly and raucous and opinionated. I am those things too, and I therefore immediately recognized in him the vulnerability that lay underneath. And in the immediacy of his work, it’s not hard to see that vulnerability stream through it all, soft and quiet and yearning. He raged against the exclusionary institutions of the world because he felt those institutions had shoved him aside. He shouted because those institutions tried to tell him that he had no voice. This rage, this shouting, this insistence on difficulty and thorniness and wit makes space for affinity, allows the like-minded to feel less isolated. That is trying work for the vulnerable. There are a handful of people in my life who showed me that I was not alone, who provided an example of how I could be in this world. Richard was one of those people, for me.

The last time I saw Richard was in Berlin, in 2016. We crossed paths less and less frequently, what with him having moved to Montreal and then to New Brunswick. Nevertheless, one or the other of us would fire off the occasional message, usually directing the other’s attention to some funny bit of scandal. I had great hopes of watching Richard grow old, catching up and gossiping along the way, two natty old fags growing older. That we would keep crossing paths in the same way we used to when I would be sauntering up Rusholme Road, and see Richard watering the foxgloves by his front staircase, and we would pause and natter and gossip and guffaw and put the world to rights.

And now I will never see Richard again.

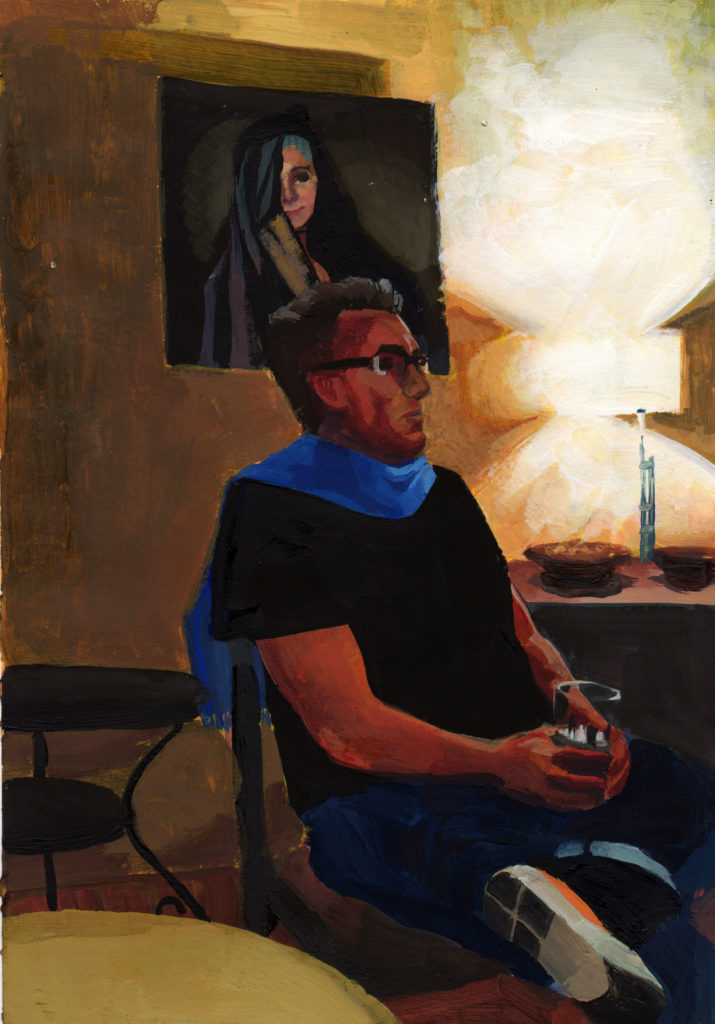

Sholem Krishtalka, Richard, 2013. Gouache on paper. 29.7 x 21.8 cm. Courtesy the artist

Sholem Krishtalka, Richard, 2013. Gouache on paper. 29.7 x 21.8 cm. Courtesy the artist