What is unrealized work? Do orgasms count?

The notebooks of Kate Craig came out of an archive of her work found in the basement of Vancouver’s Western Front in 2012, a decade after her death. Craig was a media artist, archivist, curator, video-maker, puppeteer, art punk and the sole female founding member of the artist-run centre in 1973. Her archive, which was subsequently accessioned and assimilated into the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery’s holdings, contains the usual analog stuff: correspondence, programs, catalogue entries, typewritten CVs. But there are also hints of the daily rituals and ongoing performances of a playful and at times riotous avant-garde philosophy, which dominated Western Front during Craig’s resident reign.

She was also known as Lady Brute.

In a little black journal marked “1973,” Craig outlined plans for a future video project: a montage of scenes depicting “a day in the life” of Lady Brute, the glamourpuss, paparazzi-loving attaché of Dr. Brute, a salivating villain with a penchant for sexual violence and the sleek chrome of a revolver, a character developed and executed perfectly by Western Front co-founder Eric Metcalfe. After their marriage in 1969, Craig and Metcalfe embodied these roles in a porous, inflammatory combination of play, art and life, on the fringe of straight society in Vancouver. Their characters were based on contemporary theatrical performance methods, informed by Fluxus, and on Metcalfe’s fascination with pulp fiction that began in adolescence and was tinged with the darkness of boyhood and the normalized misogyny of midcentury mainstream culture.

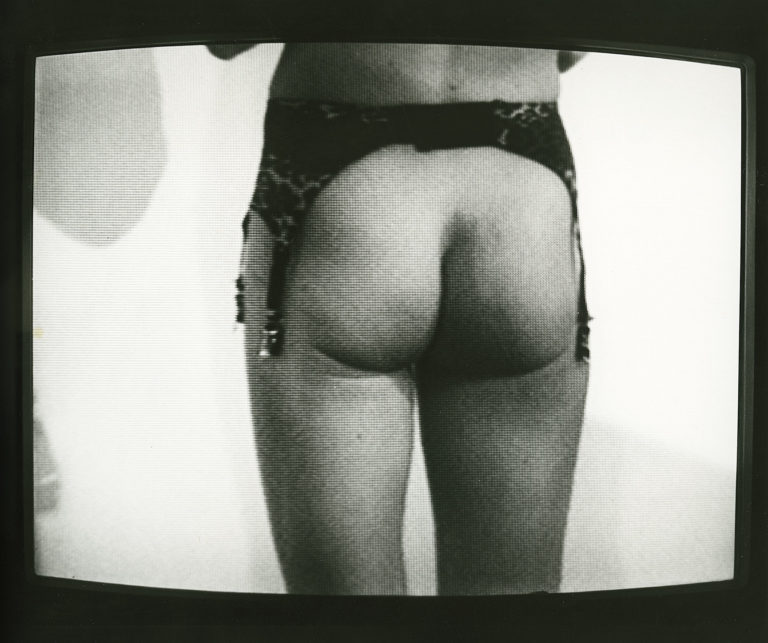

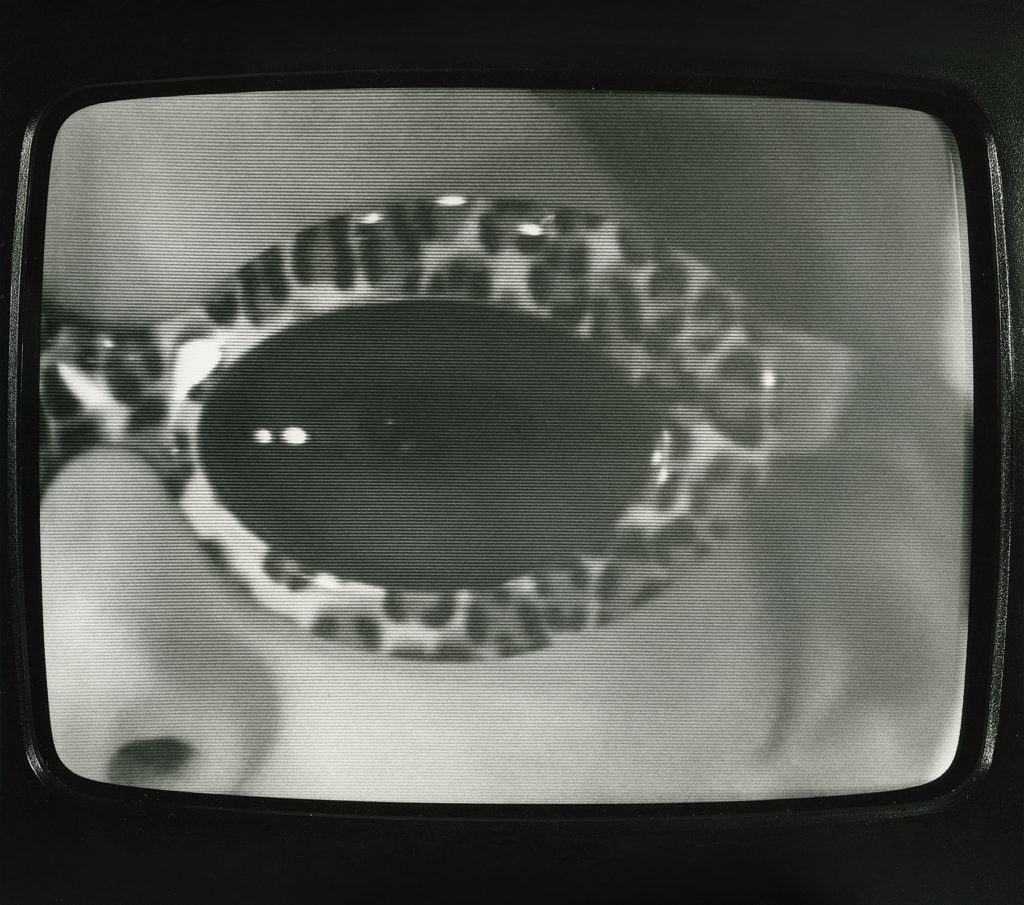

Kate Craig, Skins (still), 1975. Single-channel video, 1 hour, 3 minutes. Videographer: Hank Bull. Courtesy Western Front.

Kate Craig, Skins (still), 1975. Single-channel video, 1 hour, 3 minutes. Videographer: Hank Bull. Courtesy Western Front.

Kate Craig, Skins (still), 1975. Single-channel video, 1 hour, 3 minutes. Videographer: Hank Bull. Courtesy Western Front.

Kate Craig, Skins (still), 1975. Single-channel video, 1 hour, 3 minutes. Videographer: Hank Bull. Courtesy Western Front.

Craig’s plan for the video included vignettes that ranged from the banal to the decadent—a scene at the post office, which would end in chaos (an early version of “going postal”?) and a street scene in which the Lady’s adoring acolytes would be seen with her, dressed in their leopard-print finery. For the video’s central action, Craig had one ultimate pleasure in mind: a fetish sex scene.

Her text reads, in looping scrawl: “Should the lady be with the brute or should it be a dildo sequence? Sure would be nice to get it on with a leopard or a cat. Would a dog do?”

What is the difference between nails down your back and claws in your thigh? The relativism and life-play at the core of BDSM is at work in Craig’s plans, and one wonders how she would have pulled it off. Would she be so bold as to have the Western Front’s resident cat co-star? What happens on camera when a pussy won’t consent? These questions remain; no record of the video, besides this document, has been found.

The year before this journal entry and its planned video, a landmark work arrived in mainstream culture: Alex Comfort’s best-selling The Joy of Sex, with its bold, illustrated dramatizations of sex and its attached taboos and fetishes. The normalization of sex that came through Comfort’s popularity was, however, not the same as the fleshy and unrestrained depictions seen in multimedia work at the time, particularly by American feminist artists like Carolee Schneemann, who would have been on Craig’s radar. Indeed, Schneemann later visited Western Front, and is rumoured to have eaten lobster and drunk champagne in residence, living up to the hedonism of her own work and that of her counterparts at the centre.

Schneemann’s autobiographical trilogy of films, which she made between 1964 and 1976 with co-stars James Tenney and her cat Kitch, come to mind. Schneemann’s work from the 1960s is about taking pleasure in the human form; a sensuous and animal touch runs through her works. In Schneemann’s first film in the series, Fuses (1964–67), a voyeuristic Kitch watches Schneemann and Tenney have sex; like Craig’s oeuvre, the inclusion of a non-human counterpart further distances hetero-humannormative play from an expansive and subversive arena in which feminists could operate in the vanguard of film, video and performance.

Craig’s notebook plans can be read as an act of progressive detachment from the sexual status quo of Vancouver society at the time, and a statement toward the power and social change implied by the sexual freedoms that video, as a medium, offered.

Craig’s hallmark 1975 video, Skins, shows her standing naked before modelling all of her leopard-spotted pieces, and then packing them away. We might read this as a divestment from Lady Brute, and likewise read her earlier planned and unrealized work as a departure from sexual pleasure centred on anyone other than herself. If Skins is the final dissolution of a relationship, where the Lady disentangled herself from the Brute, and in which Craig proclaimed her artistic independence from Metcalfe, the possibility of a masturbation scene could have been a first step, a moment of pursuing pleasure on her own time.

It was never decided what would happen in Craig’s bed. Self-pleasure, and even possible interspecies coupling, would have removed the Brute from the Lady’s love life. The proposition of Craig’s unmade video does not faze, but nor does it please entirely. Once you’re past the initial discovery—the sweet chill running down your spine and pleasure buzzing in the back of your neck—the trace that remains is not enough. It’s a lonely proposition, to think back to an erotic past, one that was never fully realized and is now accessible only through yellowed page corners and mysterious stains.

The work of Craig’s pleasure remains unfulfilled.

Kate Craig, Skins (still), 1975. Single-channel video, 1 hour, 3 minutes. Videographer: Hank Bull. Courtesy Western Front.

Kate Craig, Skins (still), 1975. Single-channel video, 1 hour, 3 minutes. Videographer: Hank Bull. Courtesy Western Front.