The air was thick with White Guilt™ in early June and, as always, I was scrolling through Instagram. As people posted and debated the well-meaning but controversial #blackouttuesday squares on their feeds, galleries and local artist-run centres (ARCs) had begun to post their own statements regarding the lack of Black representation in their programming.

One ARC statement I saw rubbed me the wrong way. It was well done: they had paid a Black person to help consult; they had made semi-specific acknowledgement of the issues at hand; and they had recently made their workforce more diverse. But still, there was a sitting discomfort, the largely unspoken truth bothering me: Could I remember that gallery ever showing a Black artist?

Simultaneously, I faced a different kind of unease: I have always been an anxious type, but I feel that a tactical anxiety, when responsibly managed, can be useful. Not being a fan of confrontation, I try to avoid saying anything controversial without being able to back myself up. Wanting to say something regardless, but aware of the potential risks, I went through that ARC’s web archives, checking to see if any artists shown there had been Black.

Later, I responded to their post, saying they seemed to have shown only two Black artists in the past decade. I openly wondered why, rather than vaguely saying they had let the Black community down, they did not openly state that they essentially did not show Black art—and then work from there.

The boulder began to roll.

Beyond genuine love and care for Black, Indigenous and otherwise racialized artists, as well as the local artist-run scene, perhaps the brief tragedy-underscored air of Black power that had settled around our communities this past summer enabled an assertiveness in me that was unusual.

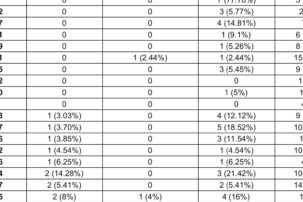

In the ensuing months, with the assistance by some peers of mine—Levin Ifko, Alicia Buates McKenzie, Uii Savage and Michaela Bridgemohan—I got to work, researching the prevalence of exhibitions of Black artists at artist-run centres in Mohkínstsis (so-called Calgary). The results were posted online in September.

It may be “unprofessional” to admit that our research project gathering the exact number of Black artists shown in Calgarian artist-run centres came about because I felt a little pissed off and hurt, but in the interest of being honest and human, and the fact that one can both have feelings and be professional, that is exactly how it began.

I simply could not stop thinking about art spaces, especially smaller ones in so-called Calgary, and how rarely they seemed to show Black artists. How many of the other Calgarian ARCs were the same? A Toronto artist, Ibrahim Abusitta, did an audit in June on Black creatives represented in his city’s major commercial galleries, and his efforts inspired my sudden choice to do something similar in Calgary, but with a different approach for a different community.

The support and insight of others helped me move forward in the face of doubts. At a vigil in June, sisters Sinit and Semhar Abraha, students at the University of Calgary, extolled the importance of race-based data in anti-racist efforts, something I internally clung to for self-validation. And without my peer collaborators, Levin, Uii, Alicia and Michaela, this project would be just another fizzled-out idea of mine.

Unsure of how the community at large would react, I tried to think of as many rebuttals or dismissals to our research as possible and consider them in how I shaped the audit as it stands today. Anticipating excuse-making if data were presented without context, I decided to create an accompanying essay. There needed to be little room for justifications around why Black artists don’t get exhibited—even if such excuses continued to be spouted when our data was released.

For instance, looking to conversations I’ve observed surrounding these matters, I have noticed many people chalking up any deficit of Black artists in our galleries to there “simply not being many Black artists.” I tried to challenge this “reasoning” in the contextual essay.

Such rebuttals are not unique to Calgary. Abusitta’s data demonstrated that even a deeply multicultural and “Blacker” place like Toronto has similarly pathetic numbers for showing Black artists. Can we expect Black artists to fare any better in Winnipeg? Halifax? The world outside of majority-Black communities, period?

While our audit focused specifically on Black artists in Calgary, patterns in the lack of representation grew obvious as we worked. While the Chinese community here seems to be relatively well represented, thanks in part to Su Ying Strang’s great work as director at The New Gallery (TNG), there has been very little Filipino art shown in this city despite a significant Filipino presence.

More Indigenous, Métis and Inuit art has been shown in artist-run centres since 2017, the so-called “reconciliation year,” which is excellent, and more funding and grants have become available to show Indigenous art. However, as Lindsay Nixon shows in their August 2020 special report for the Yellowhead Institute, titled A Culture of Exploitation: “Reconciliation” and the Institutions of Canadian Art, there are many questions about the motivations behind institutions showing more Indigenous art. One of the main questions surrounds the amount of funding and social capital a non-FNMI (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) parent institution receives versus an Indigenous artist and their community—and there are artists who have felt pressure to make stereotypically “Indigenous” art. One of the anonymous interviewees states that “There seems to be a quota for sure and lots of talk in the whisper network about institutions and non-profits that [exhibit and hire more FNMI artists] to qualify for those nice Indigenous grants.”

Nixon sums up these issues regarding the exploitation of Indigenous art by noting an “essential shortcoming of Indigenous cultural management Canada: tokenistic Indigenous representation of a select few, without shifting historical exploitation of Indigenous communities, is enough to gain easy funding for Canada’s cultural institutions.” These problems should be examined both in Indigenous art now and considered in wider future anti-racism efforts in the arts. Will we, as Black, Indigenous or otherwise racialized artists, feel forced into stereotypes and seen through the white gaze as race first, artists second? Who is helped, the community or institutions? Will we be genuinely included for our merit and the fact that we too are community members, or will we be tokenized, merely used for the money or clout that being perceived as anti-racist can bring?

Beyond being somewhat vexed at what the research revealed, such as that one Calgary gallery showed about three times more Icelandic artists than Black artists, we faced numerous challenges, concerns and limitations working on this project. As a grassroots collective, my colleagues and I gave what we could from our busy lives, and there was only so much I could do at once, especially as a mixed-Black artist to whom this was personally affecting. Limiting our scope to ARCs in general helped decide which spaces to include.

The question I am asked most is whether certain art spaces will be added to our data in the future—and the answer is “maybe.” I encourage those who are curious about other spaces to seek out these answers themselves and share their findings. I care a lot about these issues and enjoy the work, but I’m also a student. Summer has ended and I no longer have the capacity to do lots of free labour, passion project or not.

We were also asked if we were going to collect data on other types of “minority” artists. While we decided to focus only on Black artists given that Black issues haven’t always been given dedicated space, that was something we had considered. A future expanded effort, one that may extend beyond race, such as to include Deaf/Mad/Disabled artists, for example, would require more research and resources to account for the ethical sensitivities of such work. Many people may not publicly disclose or wish to disclose that sort of information, and one would need to find a way to gather information from those communities without being either presumptive or invasive.

In retrospect, the one piece of data I truly regret not gathering is the total number of shows galleries had each year, as the percentage of shows given to Black artists would be even more useful. If I rework the audit in the future, I want to collect this information, as well as see how many Indigenous artists were shown.

Looking forward, I hope the audit can be helpful. I don’t like the idea of pointing out a problem and not trying to solve it. I can’t claim to have any answers yet, but people have already been looking for them. Community involvement seems important. I look again to The New Gallery, who are site- and community-responsive in their general but nonexclusive focus on Calgary’s Chinatown and Chinese diaspora.

In her recent talk “Artist-run Methods for Collaboration and Community Building,” Su Ying Strang reiterated the importance of galleries actively looking to see who is not included in their programs and spaces. Feeling a responsibility to its location in Chinatown, TNG did its research and worked with minimal but well-designed resources. They went out of their way to make their space accessible to the community, including translation of show texts by an art-versed translator into traditional Chinese languages, conversations and tours with interpreters, and focused invites sent specifically to certain community sectors, such as seniors. They also made sure to participate in and volunteer for their communities in Chinatown and the arts, and support their continual intersections. While I am currently more in favour of massive restructuring of systems, I think there is a lot to be learned from TNG’s community-responsive approach, including that there is proof that it works.

Zarina Muhammad’s article FUCK THE POLICE, FUCK THE STATE, FUCK THE TATE: RIOTS AND REFORM, published by art-criticism collective The White Pube in June 2020, has also been inspirational. It explains that “decades of diversity policy and the attempts at inclusion in the arts are a history of continual institutional failure,” and that “reform in the arts represents a static position; it places a heavy focus on a politics of representation [and] inclusion, and assumes that diversity in and of itself is an end point.”

In other words, there is no decolonizing colonial institutions; change will come only from dismantling them and rebuilding structures not rooted in whiteness or capitalism.

I can also only hope we see lasting changes from this moment on. I hope we collectively begin to address the root causes of a lack of genuine representation. I don’t want galleries to ask why Black art isn’t “good” or “refined” or “Black” enough; I want them to ask why their own tastes are exclusionary.

Here’s some advice: Don’t say that there aren’t a lot of Black artists around; ask what the Black community wants, make the community feel welcomed, give space to the community. Don’t wait for the complaints to come; be actively aware of potential ways racism, colourism, colonialism, capitalism, ableism, et cetera, can contribute to the alienation of those around you.

The artist-run not-for-profit model has a lot of potential. Artist-run centres had their beginnings in a critique of dominant art-world structures. They suffer from a lack of funding and are often based too closely in the harmful hierarchies of the art world, but are run by those in the community, and are not driven by profit or selling work.

The places I have “called out” have been very receptive, kind and open. Though these reactions were unexpected, I was luckily able to pay myself and my colleagues for our efforts thanks to the advocacy of multiple people from the very places we were auditing and the Alberta Association of Artist-Run Centres. I am grateful for this support.

This has been the first time, with the release of this data and ensuing conversation, that I feel I have been taken seriously by my community at large. I hope that other Black artists and community members will be able to share that feeling too.

Figure 2 from

Figure 2 from