Many events this year—such as the expulsion of Russian diplomats in the West and the intense international attention on the Korean peninsula—have suggested the return of a Cold War mentality in Canada, and well beyond.

Yet few Canadians are aware of the original Cold War’s deep impact on our national cultural policy—or of how those legacies from the 1950s are still strangling our imaginations in 2018.

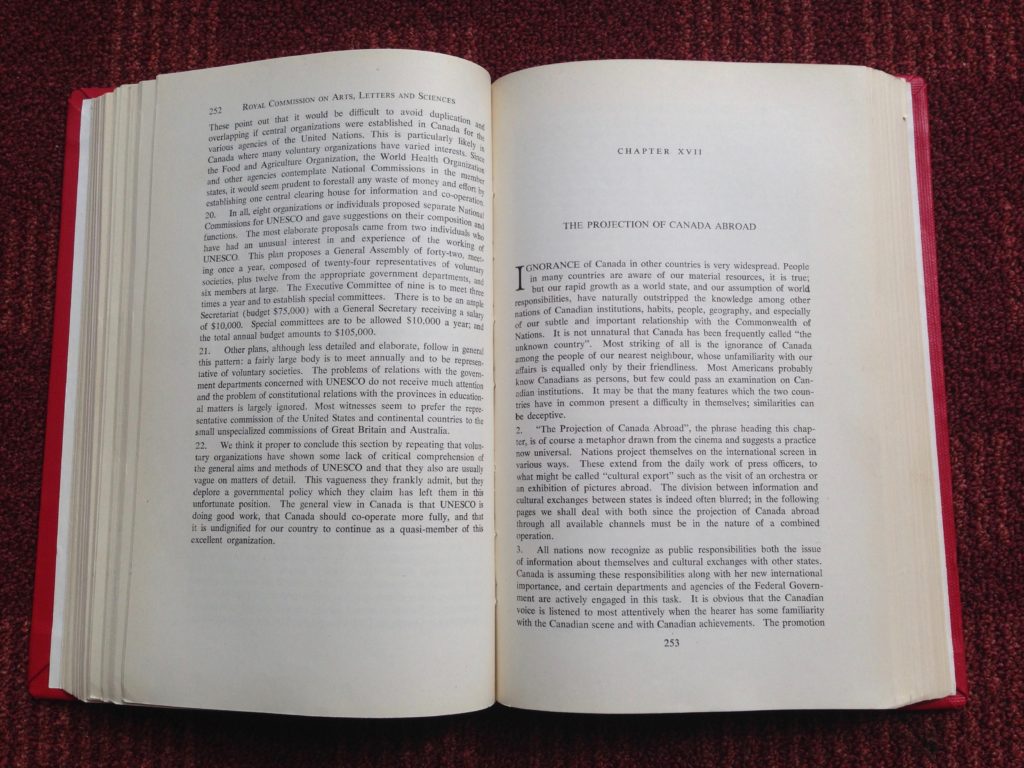

In 1951, the final report of Canada’s Massey Commission (a.k.a. the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences) was released. Better known as the Massey Report, this document provided the armature of what would become a state-defined national culture in Canada and give birth to the idea of Canadian content.

But the Massey Report has not allowed us to grow. It has robbed agency from artists. And the contemporary contradictions that have emerged in Canadian art and its institutions still flow through this mother of all policy documents.

What I hope to do in this essay is make some of these detrimental connections clearer. I want to make the case for replacing the Massey Report—an out-of-date document premised on elitist, Eurocentric, 19th-century notions of culture but that, in the strangest and most distressing manner, continues to define Canadian society.

The Massey Report and its ethos still leads to policies which define, officially, what that Canadian “culture” and “content” is—to the exclusion of much actual Canadian art-making and actual Canadian artist experience.

What Is Canadian Art, Really?

Looking at what the results of the Massey were, and how quickly they emerged, is important.

For instance, fresh with the Massey Report’s impetus to foster the “projection of Canada abroad” (as one of its chapter headings put it) Canada organized its first independent participation in the Venice Biennale in 1952.

The curatorial politics implied in this first Venice participation (justified by the Massey’s philosophical leanings) is well analyzed by Sandra Paikowsky. This exhibition of Canadian culture as paintings by Emily Carr, Alfred Pellan, David Milne and Goodridge Roberts, she writes, “raises issues surrounding the presumption of an official national art and the institutional authentication of culture.” It is also aligned with making culture part of a project of consolidating political power in the international (with an emphasis on European) sphere.

The leaders of the “national” art identity constructed back then are now well known, of course. As Joyce Zemans puts it, “as the Cold War intensified, members of the Group (of Seven) were written about as historical figures, their nationalist project something of the past, despite the fact that several members were still exhibiting regularly.” Again, art became valued mainly in terms of nationalism and encouraging a single “national identity” rather than other values.

The very sense of what defines Canadian art came out of that that writing and other 1950s activities like the ramping up of the National Gallery of Canada’s Sampson-Matthews project, which distributed silkscreen prints of landscape art far and wide: “our collective sense of what is ‘Canadian’ in Canadian art and the positioning of the land (and more particularly of the wilderness aesthetic) as the key to Canadian identity can be traced to the Sampson-Matthews project,” Zemans writes, “and, more especially, to the post-war phase of that project.”

On a broader scale, the Cold War period and the Massey Report saw a push for cultural infrastructure and institutionalization of state support—all as a central part a nationalist narrative. It established the rationale for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the National Film Board, the Canada Council, the National Gallery, the National Archives, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the National Library, among other institutions.

These institutions are vital to many artists today. But there was a cost then to promoting this particular idea of nationhood and culture put forth in the Massey Report. And there is still a cost now.

Members of the Massey Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, and Sciences in 1951. Seated from left: Montreal engineer Arthur Surveyor, committee chair and University of Toronto chancellor Vincent Massey, and UBC president Norman Mackenzie. Standing: Laval University's Georges Henri Levesque and University of Saskatchewan history professor Hilda Neatby. Courtesy University of Toronto Archives.

Members of the Massey Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, and Sciences in 1951. Seated from left: Montreal engineer Arthur Surveyor, committee chair and University of Toronto chancellor Vincent Massey, and UBC president Norman Mackenzie. Standing: Laval University's Georges Henri Levesque and University of Saskatchewan history professor Hilda Neatby. Courtesy University of Toronto Archives.

The Problem of Nationalist Art Narrative as Policy

What happens when you put forth a certain idea of nationhood and culture—whether in the Massey Report or elsewhere—is limitation to a single narrative or set of narratives. And that’s a huge problem, one that still needs fixing.

“As far as the legacy of the Massey Report, has been real and widespread. It is not an inclusive one,” writes Susan Crean, offering a critique and alluding to the invocations of “national identity as a cultural smokescreen.”

Crean’s insight is not new, but it is still salient. She wrote this in one of the first salvos against the Massey: her brave book Who’s Afraid of Canadian Culture? from 1976. Many of its points are still relevant 42 years later.

“The growth of arts established during this period and the Massey Report that paved the way for government subsidy,” Crean writes, “may be regarded as the effort of an elite class of patrons to preserve its own cultural forms by transforming them into Official Culture.”

On Official Culture and Entitled Aesthetics

This “Official Culture’s” set of narratives for Canadian art post-Massey has been well summed up by art historian and curator Debra Antoncic:

“Art historians and curators who have investigated the post-war period in Canada have focused primarily on formal aesthetics, conflict between proponents of abstraction and representation, and expressions of Canadian national identity in work by Canadian artists,” she writes.

What’s more, the stories Canada has told itself about culture post-Massey glorify only certain curators or collectors.

“The narrative of Canadian cultural maturity that has developed since WWII is typically framed around charismatic, dedicated and newly-professionalized curators who persuaded a reluctant wealthy class to support the arts in the name of civic and/or national public service,” Antoncic notes.

That set of art stories from the 1950s continues to echo in the 21st century, be it in an American appointment in a leadership position in Canadian cultural institution; in the outdated collection mandates of art galleries and museums; or in the very urgent issue of nationalism impacting cultural politics.

These are art narratives that continue to surface and resurface in 2018, given the relative sense of safety and authority that certain “approved” aesthetics and stories provide to both curators and artists.

Writer and curator Amy Fung has termed this problematic tendency “entitled aesthetics”:

“I am speaking to the lineage-chasing artists and curators who choose to regurgitate canonical aesthetics from decades past…Entitled aesthetics inbreeds a type of navel gazer who do not understand that aesthetics are time-sensitive tangents born of socio-historical contexts.”

As old narratives repeat, their biases both become more powerful and, to those in power, more invisible.

“For the genre of experimental cinema, like Abstract Expressionism in painting, or like Beat poetry in literature, the canon has been filled by a very narrow demographic that benefited from a post-war condition that turned towards abstraction in form and content as a reflection of the world,” Fung writes, “and at the base of this, of course, is a systematically racist, sexist, and ableist society.”

It’s clear that in 2018, the old 1950s armatures of Canadian culture are no longer sufficient. But what can come next?

The original Massey Report and its legacy strangled an emergent public which did not have a provenance in Anglo-Franco heritage. It consolidated elite power and served to subvert and defund art and artists that did not fit its “official” vision, whether in medium or in mindset

Cultural Policy as National Power Play

Before we can answer that question, it is crucial to reflect further on how the Massey Report is an outcome of ideological polarity of the Cold War period—when freedom-versus-totalitarianism and capitalism-versus-communism were pitched as a battle for civilization.

And since the Massey Report, the imperative of support to sustain the arts has been advanced and defended as an important function of the modern nation state.

“If one were taking a postcolonial position such as that advanced by [Partha] Chatterjee, one could argue that this move stands directly in the tradition of colonialized governments, which are endowed with the dual task of producing difference and sameness,” writes Jody Berland. “Make Canadian culture, call it Canadian culture, prove that Canada has a culture, and ensure that it functions well in the world market.”

On the political home front, the Massey’s dismissal of the idea of “amateur” artist communities and artist activism also had ideological roots and effects.

Maria Tippett, in her book Making Culture: English-Canadian Institutions and the Arts Before the Massey Commission, suggests that the appointment of the Massey commission was a result of a direct threat posed by the increased support for the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation in Canada (the precursors of the present-day New Democrats) whose platform outpaced the Liberals in advancing the agenda of a national culture. The history of community arts centres and multiple folk traditions was swept away by a Trojan Horse of the elite, who invoked defense of nation and sovereign in putting forward their own notions of official culture.

And as Robert McKaskell has pointed out, the Massey Report resulted in a huge decline in influence of voluntary societies and artists groups in the 1950s, their role effectively replaced by the National Gallery and the Canada Council.

These effects of the Massey Report combined to consolidate the existing powers in Canada, whether in politics or in the arts.

Time for a New Framework

Even though Cold War echoes grow louder politically and economically, both nationally and internationally, now is the time for the Massey Report’s hold on Canadian culture to wane.

In my view, it is high time in Canada for a new commission, perhaps a new framework, to be set up that has a whole different set of voices involved—a commission and framework that does not rob artists and communities of artists of their agency to contribute in the making of the nation.

But in reimagining Canadian culture in 21st century, how can we truly avoid the claptrap of the Massey Commission’s imagination? How can we break those shackles to truly embrace a Canadian culture beyond the confines of a two-founding-nations plank?

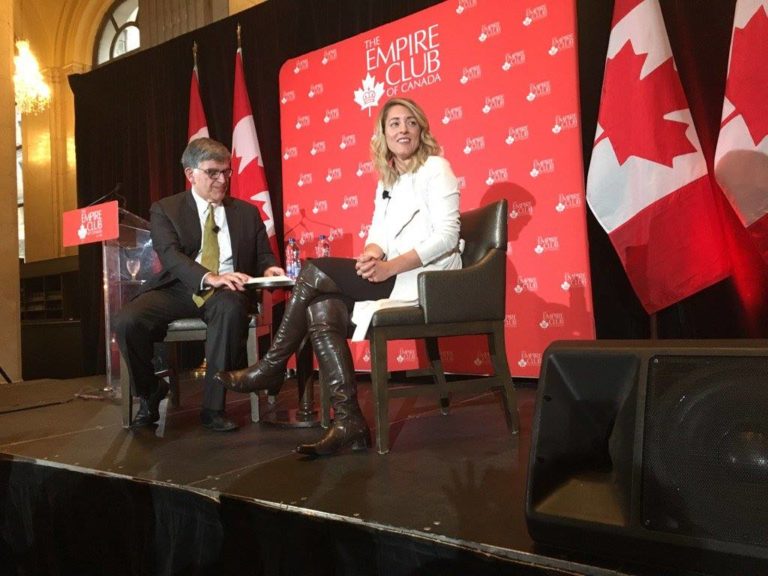

In fall 2017, Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly tried to update the Massey Report with a new Creative Canada strategy. Launched with talks at the Economic Club of Canada and the Empire Club of Canada (pictured), the strategy was widely panned. Photo: Facebook.

In fall 2017, Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly tried to update the Massey Report with a new Creative Canada strategy. Launched with talks at the Economic Club of Canada and the Empire Club of Canada (pictured), the strategy was widely panned. Photo: Facebook.

Learning From Past Attempts

It is essential that any new commission revising the Massey be aware of its history, and tendencies to repeat it—tendencies that are strengthened by the power imbalances that Massey and its legacy has fostered.

Two other attempts so far to revise Massey Report strategies have not created the change we really need—a more equitable art and art realm in Canada.

In 1980, the feds struck the Federal Cultural Policy Review Committee, which released what would be come known as the Applebaum-Hébert reports of 1981 and 1982.

Yet the Applebaum-Hébert reports mainly served to provide economic (and not just political, as per the Massey) arguments for culture in Canada. It separated Canadian culture in two—public good and private good—without fixing the problems of “official culture” articulated by Crean back in the mid-1970s, and still potent today.

Fast forward to fall 2017, and we had the much-fanfared debut of Creative Canada, branded as an overhaul of “national cultural policies” for the digital age—and which some hoped would again provide a much-needed update of the Massey. Again, they were disappointed.

“The rationale inherent in the government’s plan will turn the leaders of Canadian art and culture into followers of big data,” Ira Wells wrote. “Creative Canada won’t protect the distinctiveness of Canadian art but will shackle it to the homogenizing logic of corporate analytics. The result will be a more calculated, data-driven, snackable Canadian culture, one chasing web hits abroad in order to justify its funding at home.”

It is clear that government efforts in the 1980s and 2010s to revise the Massey have served only to exacerbate the power imbalances and inequities that the 1950s embedded in Canada’s cultural sphere and ideas of nationhood.

Any attempts moving forward must learn from those past attempts, and do better.

Artists Must Lead the Process

The original Massey Report and its legacy strangled an emergent public which did not have a provenance in Anglo-Franco heritage. It consolidated elite power and served to subvert and defund art and artists that did not fit its “official” vision, whether in medium or in mindset. And in later decades it played into the rise of economically valuated modes of government-supported art.

Efforts made to correct this situation are often superseded by the structural biases inherent in the system. In 2017, I spoke about the Massey Report’s exclusionary legacy at the Arts and Literary Magazine Summit at the invitation of Hal Niedzviecki. I did not miss the irony of that moment in following weeks as controversy played out around Niedzviecki’s own views on cultural appropriation.

But the good news is this: many artists over the past 65 years have kept working, kept resisting, kept refusing and kept reinserting their work into official narratives. From the creation of artist advocacy group CARFAC in 1968 to the founding of the Professional National Indian Artists Inc. in 1973 to the In Visible Colours event I organized in 1989 to the writings by Ken Lum, Paul Litt, Dot Tuer and others critiquing Massey in the 1990s, to ways many artists and allies resisted the big #Canada150 push in 2017, dissidents and activists have been changing and challenging the realm of “official Canadian culture” for decades.

These activities are proof that we don’t have to keep sustaining Cold War–style divisions, and their divisive values, in our arts and culture communities. And we don’t have to keep these values embedded in the very idea of Canada, either.

But we need better policy approaches and paradigms to reflect that. And we need them now.

The Massey Report, published in 1951, still shapes Canada's arts policy today. Its emphasis on “the projection of Canada abroad” and the necessity of “cultural export” as means of building power is echoed in current government strategies.

The Massey Report, published in 1951, still shapes Canada's arts policy today. Its emphasis on “the projection of Canada abroad” and the necessity of “cultural export” as means of building power is echoed in current government strategies.