In late September, 1969, five Canadian and two American art workers travelled to Inuvik in the Northwest Territories as a kind of postscript to the exhibition “Place and Process” at the Edmonton Art Gallery. Artists Lawrence Weiner, Harry Savage, and the N.E. Thing Co. (Iain and Ingrid (then called Elaine) Baxter), EAG director Bill Kirby, writer Virgil Hammock and I spent all of 39 1/2 hours in Inuvik, then a raw, “new town” being built by the federal government on the Mackenzie River Delta, some 120 miles north of the Arctic Circle. A number of conceptual artworks were executed, none of which addressed the political and environmental implications of our brief intrusion, or the plight of the Indigenous inhabitants (Inuit, Dene and Métis), many of whom had been involuntarily relocated from the nearby town of Aklavik.

Although I have never returned to the Arctic, rereading my account of the trip (“Art Within the Arctic Circle” in the Hudson Review) almost 50 years later, I am struck by the fact that the issues we noticed then have since come to the fore nationally and globally. I described Inuvik as “a redneck town with an overnight population of well-dressed businessmen (many of them German and American) who come in to set up further exploitation plans.” Were we, as art workers from the south, to visit the area today, we would be far more knowledgeable about the Arctic’s unprecedented warming and its changing ecosystems, about Indigenous rights trampled by the presence of military interests and fossil fuel industries, about destructive roads and pipelines threatening wildlife and sacred spaces. (The standoffs at Standing Rock were a teaching opportunity for the entire continent.) Artists are all too often the flying wedge of gentrification. We arrived on the first-ever passenger jet to land in Inuvik. However, even in our ignorance, we were appalled by the blatantly inequitable social conditions in the so-called “transitional area” that was already labelled “one of Canada’s newest slums.” Farley Mowat wrote this in reference to west Inuvik, or “Happy Valley,” where Indigenous people lived beyond the pale of the utilidor line, an above-ground water and sewage system that connected the other (upscale) side of the town, providing the non-Indigenous population with adequate services and protection from the elements.

In 2018, neither Conceptual art nor the Arctic are what they were in 1969. The term “conceptualism” has broadened to the point of uselessness by incorporating any object or installation in which idea or content plays a significant role. But I’ll stick to my story from the mid-1960s, that true Conceptual art is “dematerialized,” which (at this point in time) disqualifies the current work of many of the pioneering Conceptualists. In an acute retrospective essay on “Place and Process,” Charity Mewburn noted the younger artists’ “antagonistic attitude” toward Greenbergian orthodoxy (an attitude I shared with a vengeance), suggesting that the Edmonton exhibition, given its virtual absence from the historical record, itself fell victim to the very colonization it set out to critique. Although I doubt if that was the goal of “Place and Process,” I am intrigued by her interpretation of Weiner’s The Arctic Circle Shattered (produced by several blasts of a shotgun on a rock) as “a succinct visual metaphor” for American colonialism, and NETCo’s Territorial Claim, in which Iain Baxter “marked” (pissed) an imaginary borderline, as a Canadian response.

As for the Arctic, it is, as we all know by now, among the fastest-warming areas on a fast-warming planet. (My favourite protest sign reads: “The Climate is Changing/Why Aren’t We?”) By the 1960s, the centuries-long search for the Northwest Passage had resulted in territorial disputes and become a national independence issue, especially in 1967, Canada’s centennial year. As an American, I was unaware of the extent to which Canadian national identity was tied to the aura of the legendary “North.” Nor did I understand that by concentrating on the bleak, featureless terrain of the subarctic, NETCo might have been mocking (or at least confronting) earlier Canadian artists’ idealizations of the region. Climate change is opening up the Arctic to tourism, industry and the military, abetting the ongoing invasion of global oil interests and further exposing long-hidden Northern cultures to continued exploitation as well as environmental destruction.

Today there are nine hotels in Inuvik, and a mosque; the main tourist attraction is an “Igloo Church.” But on our one night there in 1969 there was no place to eat, so we were forced to attend the grand opening of the Eskimo Inn—complete, as I noted then, with “pink alcoholic punch and soggy hors d’oeuvres.” Of the few Indigenous people attending, even fewer were interested in entertaining the entrepreneurs with step-dancing; one “overdressed lady” complained, “We gave them drinks and now they won’t even dance.” “The Eskimo Inn is not for Eskimos,” said a young Indigenous woman bitterly.

For many of us, the Arctic is a mythical land of ice and snow. While curating an exhibition on climate change at the Boulder (Colorado) Museum of Contemporary Art in 2007, I couldn’t resist the glowing blues and whites beloved of photographers near the Poles. On arrival in Inuvik decades earlier, I noted that the tundra wasn’t as “exotic” as I’d expected, with frozen ground, some snow and ice, and temperatures around 15 degrees Fahrenheit. A recent extreme high for September was 79 degrees; in February of this year, the Washington Post reported that the region is “stewing in temperatures more than 45 degrees above normal.” The tundra is giving up its greenhouse gases to a world that has asked for it. I was surprised, rather than disappointed, at how the landscape of the western Arctic differed from the conventional image of the Arctic. What impressed us was “the space, and the infinite sameness of the terrain, the very subtle color range illuminated by a sharp, even light which has a terrible clarity.”

The purported focus on place in late ’60s and early ’70s land art was actually a focus on site. Place, or the cultural landscape, is where land and lives meet. In the interim, land use and lived experience has become more interesting to me than landscape. When Edmund Carpenter wrote in 1966 that “Eskimos” were not interested in scenery but in action, existence, he probably knew nothing about the emerging international trend of Conceptual art—but this would have been a telling insight for artists at the time. Ingrid Baxter, among others, has discussed an “aesthetic of distance,” forecasting the appropriation and cultural imperialism implied by the now-infamous practice of artists parachuting in to suck up place and use it merely as site. While we would not have identified with the historic/heroic explorers of the North, our brief foray into the Arctic was, in hindsight, an intellectual adventure, a naively colonialist art-scouting trip. But it was an eye-opener, and a lot of fun. We were young, and Conceptual art, for all its serious impact, was something of a game, or a game changer.

Thanks to Bill Kirby (who curated “Place and Process” with New York writer Willoughby Sharp) for reminiscing and clarifying with me.

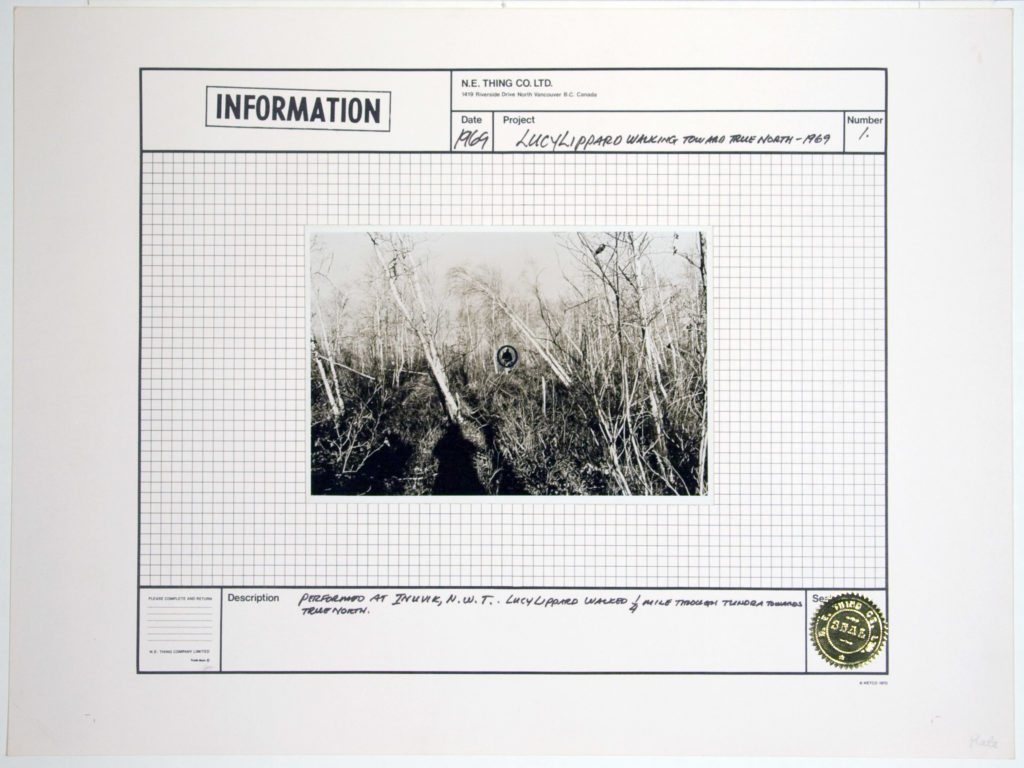

N.E. Thing Co., Lucy Lippard Walking Toward True North, 1969. Silver gelatin print, ink, paper, foil seal and offset lithograph on paper, 45.5 x 60.9 cm. Collection Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia.

N.E. Thing Co., Lucy Lippard Walking Toward True North, 1969. Silver gelatin print, ink, paper, foil seal and offset lithograph on paper, 45.5 x 60.9 cm. Collection Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia.