I feel an overwhelming sense of empathy while experiencing Joi T. Arcand’s solo exhibition “she used to want to be a ballerina.” It’s not that I ever deamed of being a ballerina. This empathy is, rather, because of an intimate, indescribable resonance I feel through Arcand’s sensitive typographic and photographic storytelling.

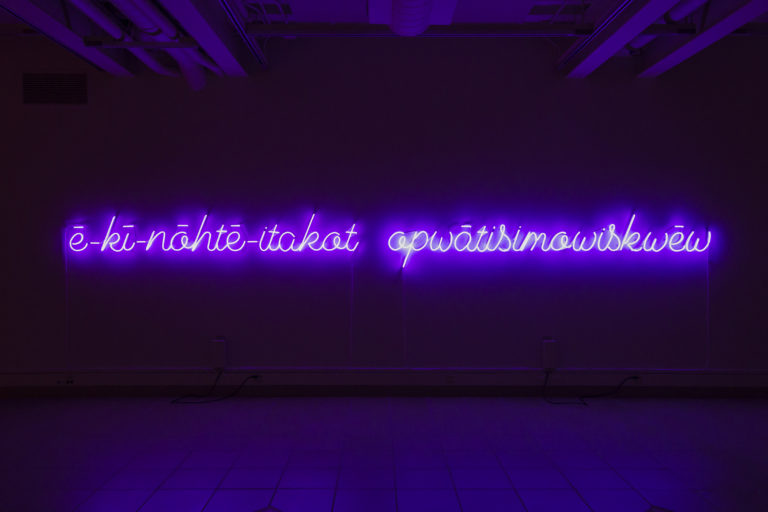

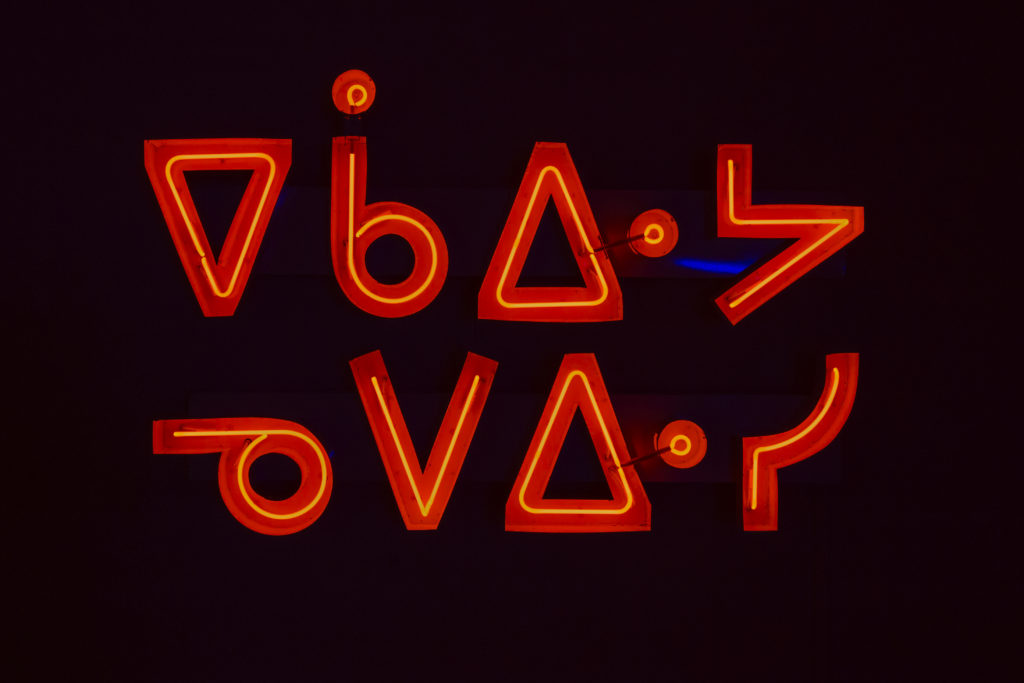

In this exhibition, Arcand, known for working with the Plains Cree syllabics, shares her childhood dreams and heroes. The first section introduces the exhibition in the manner of a prologue. Two neon texts ēkawiya nēwëpisi — (Don’t be shy) (2017) and ē-kī-nōtē-itakot opwātisimowiskwēw (she used to want to be a fancy dancer) (2019) occupy the adjacent walls bracketing the entrance. Their attractive pink and blue glow floods the gallery, suggesting a sense of melancholy ahead.

In a side room, the three photographic light boxes that compose she used to want to be a ballerina (for grandma Vivian) (2019) depict Arcand’s feet in three standard ballet positions. In a corner, a music box plays Buffy Sainte-Marie’s song “She Used to Wanna Be a Ballerina.” The pink music box, complete with rotating ballerina figurine, is covered with stickers of stars, butterflies and letters that spell “BUFFY,” “kiya” and “itako”—the latter two terms together meaning “be you.” Another kind of tribute can be found in a window display next to the entrance. Here, hot pinks and white vinyl Cree syllabics mingle with the English words “BALLERINA,” “ROCK & ROLL,” “TCHAIKOVSKY” and “PAVLOVA.” Together, this display commemorates Maria Tallchief—the very first prima ballerina in America.

Joi T. Arcand, she used to want to be a ballerina (for Buffy Sainte Marie), 2019. Jewelry box with music. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Carey Shaw Photography.

Joi T. Arcand, she used to want to be a ballerina (for Buffy Sainte Marie), 2019. Jewelry box with music. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Carey Shaw Photography.

Returning to her childhood dream of becoming a ballerina, Arcand suggests a way to exist and dream in that re-imagined world, while never letting us forget her indigeneity. There is regalia with ribbons sewn on by her grandmother, there is music from Buffy Saint Marie, and there is a tribute to Maria Tallchief. As with Arcand’s neon works, there is a restlessness in these tributes—a constant search for balance between Indigenous and Western elements. This oeuvre doesn’t seem to comfortably stay within any particular set of expectations.

In a curatorial statement, Leah Taylor mentions Arcand’s “short-lived experience Powwow dancing in her youth, and her long-lost dream of wanting to be a ballerina.” There is an unfulfillment here, a gap. And a gap is also seen, or rather, epitomized, in many of Arcand’s translations and re-interpretations between Plains Cree syllabics and English words.

Joi T. Arcand, she used to want to be a ballerina (for grandma Vivian), 2019. Three photolight boxes. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Carey Shaw Photography.

Joi T. Arcand, kī-nōhtē-itakow wāh-wihkisimowiskwēw (for Maria Tallchief), 2019. Vinyl wall paper. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Carey Shaw Photography.

The melancholy of a linguistic distance here reminds me of another work of Arcand’s from 10 years ago. Here on Future Earth: Northern Pawn, South Vietnam (2009) is a photograph depicting a streetscape in North Battleford. Two storefronts have had their English signage replaced with Plains Cree syllabics.

On top of one store in this photo, a mural depicts a group of Indigenous warriors, two horsemen, a chief and a companion standing at the edge of a cliff surveying the vast landscape beneath them—until that landscape is disrupted by a settlement fort emerging from the right side of the image. This mural is emblematic of 19th century Canadian landscape paintings by artists . Such imagery was part of official government efforts to promote settler expansion into the Canadian West. Arcand’s Plains Cree syllabic signage disrupts that historical narrative. By translating all the English words into Plains Cree, Arcand presents snapshots of an imagined world where Cree culture, untainted by colonialism, thrives.

In this “Future Earth” of Arcand’s, I also see my own country reimagined. The building adjacent to the mural is a Vietnamese restaurant in North Battleford. “South Vietnam” is a reference to the part of the country where my hometown Sài Gòn is located. My history coexists with Arcand’s here in her alternate world. We intersect at the extensive history of being subjected to colonialization under imperial power. By translating “South Vietnam” into Cree, Arcand’s work crosses cultural and geographic boundaries, inviting inquiries on ways language could decolonialize. More importantly, it urges me to reflect on the history of my own mother tongue.

Modern Vietnamese, Quốc Ngữ, became popular in 1910 when the French colonial administration mandated the use of a Western writing system based on Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum—a 1651 Vietnamese-Portuguese-Latin dictionary invented by Avignon Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes. De Rhodes’s dictionary attempted to capture Vietnamese phonetics based on Portuguese; meanwhile, the country had been using variations of Chinese writing system over a few centuries. In early 20th century, the French accelerated the adoption of Quốc Ngữ as a strategy to undermine the Chinese influence and enforce Christian and French values and language in the new colony. The integration was successful, as Quốc Ngữ has persisted through both French and American occupations and it became the national writing system after the country gained its independence. While some traces of French linguistic influence remain, contemporary Vietnamese has taken full ownership of the language. Calligraphy that stylizes Roman alphabets into pictographs is considered a traditional art form.

The vernacularization of modern Vietnamese epitomizes Homi Bhaba’s notion of the “third space,” where ideologies of the dominant and the subjugated collide. The language is a constant reminder to its people of a colonial legacy, and a promise that we will not allow it to happen again.

Joi T. Arcand, ē-kī-nōhtē-itakot opwātisimowiskwēw (she used to want to be a fancy dancer), 2019. Neon. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Carey Shaw Photography.

Joi T. Arcand, ē-kī-nōhtē-itakot opwātisimowiskwēw (she used to want to be a fancy dancer), 2019. Neon. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Carey Shaw Photography.

I find refuge in Arcand’s Plains Cree. Our languages share similar historical paths in their developments; they both exist in this third space of culture. While Plains Cree is still slowly reclaiming its sovereignty in communities, modern Vietnamese has fully gained its agency over the usage of the language with the creation of numerous regional and generational dialects.

I wonder at my inability to recognize Cree letters that signify “South Vietnam.” Arcand’s translation of the Vietnamese restaurant’s sign carries her vision of an “alternate present” across cultures, and it points toward the present Vietnam. This traversing creates disruptions, ruptures and overlaps of languages, beliefs and ideas, out of which emerges a gap of productive imagining. “she used to want to be a ballerina” actualizes that gap and makes it physical. Using the marginal modal verb “used to,” Arcand makes sure that gap stays open, unfulfilled, physical and felt.

Writing in 2018 about Arcand’s work, John G. Hampton observed that “languages travel too,” suggesting that the “foreignness” in Arcand’s work is a product of colonial monolingualism. In that sense, Arcand is dismantling the colonial hierarchy of languages, providing agency and responsibility to the many languages that co-exist in so-called Canada.

Joi T. Arcand, ēkawiya nēwēpisi (Don’t be shy), 2017. Neon channel sign. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Carey Shaw Photography.

Joi T. Arcand, ēkawiya nēwēpisi (Don’t be shy), 2017. Neon channel sign. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Carey Shaw Photography.