I’m not an investigative journalist, nor am I a statistician. I am a Palestinian Canadian member of the Toronto arts community. And as a member of that community, I was motivated this month to shed light on a problematic area within it, and on June 4, I published a spreadsheet showing the representation of artists who are Black, Indigenous or persons of colour (BIPOC) at several leading commercial galleries in Toronto. For far too long, I have known that a majority of artists represented in Toronto galleries are white. Galleries that have BIPOC artists in their roster represent a fraction of the group.

Artist-activists have used data to shed light on the gender and racial inequalities in art communities since the 1980s—and beyond.

At the end of May, I saw an exponentially increasing amount of content on Instagram that focused on anti-Black police brutalities, the Black Lives Matter movement, anti-racism activism and related solidarity. These events prompted me to convert my general awareness of bias into more concrete data. Then, the #blackouttuesday posts happened on June 2, which led to many criticisms of performative allyship. The day after, on June 3, a friend, local African Canadian artist Esmaa Mohamoud, posted an Instagram story that expressed her frustration and anger with Toronto galleries—these galleries, she noted, were showing support and solidarity with Black Lives Matter, yet an overwhelming number of them didn’t represent a single Black artist.

The research process I undertook was inspired by artists. The Guerrilla Girls immediately came to mind after I saw my friend’s story—this group of artist-activists has used data to shed light on the gender and racial inequalities in art communities since the 1980s. And in the weeks prior to using spreadsheets to point out the inequalities in commercial galleries, I had been using them to document COVID-19 cases in Canada. On a daily basis in April and May, I had been logging new coronavirus cases, recoveries and deaths. It felt important to see the numbers for myself by accessing the government websites rather than relying on news agencies. So I began my research into an older and more severe harm: systemic racism.

Toronto is often described as diverse and multicultural, but I didn’t see that representation in the rosters of these galleries.

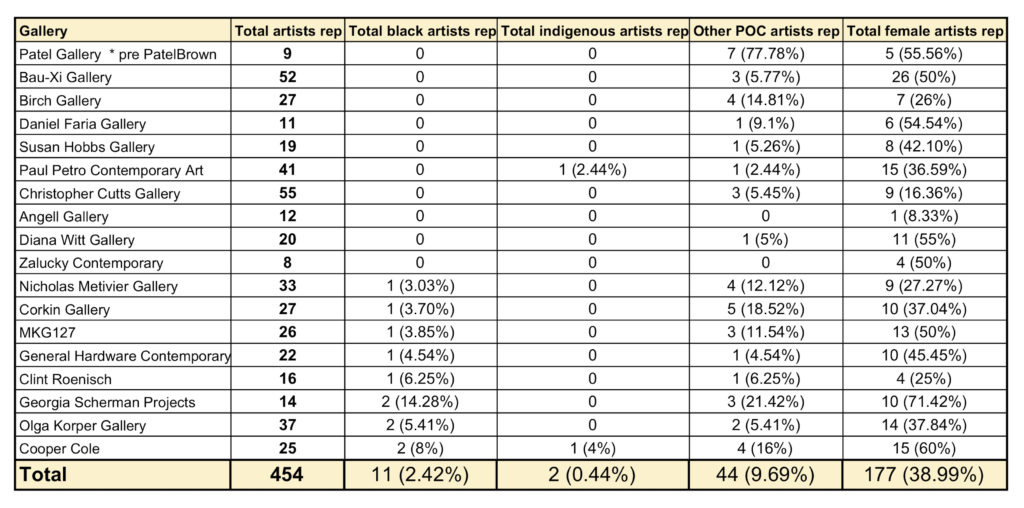

To compile data on gallery representation, I listed the galleries in Toronto with which I was most familiar and looked at their rosters of artists before researching each to know more about gender and racial identity. It is helpful that artists self-identify in many biographies. Knowing that, as a non-professional researcher, my data would have imperfections, I made sure to address that constraint in my original post—and I uploaded a second post later in the day on June 4 when I was given a correction.

The findings of my quick search did not surprise many. Toronto is often described as diverse and multicultural, but I didn’t see that representation in the rosters of these galleries. Several commenters expressed that this was not news to them, but rather an unspoken reality.

Yet there were a few other things that also jumped out to me personally as I went through the research. Although the focus of my search was Black and Indigenous representation, I inevitably noted that not one Palestinian artist was found. During my search, I did notice something I wasn’t expecting: I had learned from previous conversations with my mentor that ageism was yet another problematic area in the arts, and that younger artists often received more attention than older ones. So I was surprised in the data to find that there were a fair number of senior artists represented by these commercial galleries—however, I must note, the majority of these were older white men. I did not draw attention to this in my social-media posts, though, because I wanted to keep focus on the bias against Black and Indigenous artists.

If I were to repeat this project in the future, I’d look at collecting more data—especially on more intersections of race, gender, age, disability and 2SLGBTQIAP identities.

I also learned a lot from comments people made on the spreadsheet. While I did receive some congratulations, other community members conveyed frustration, as they rightfully felt my search did not encompass their demographic, or other demographics of concern. If I were to repeat this project in the future, I’d look at collecting more data—perhaps creating a survey that gallerists and artists could fill out to provide more information. I would include more categories that looked at more intersections of race, gender, age disability and illness, and sexuality across Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual and pansexual (2SLGBTQIAP) identities.

This project and responses to it also prompted me to reflect on the role of commercial galleries. Artists will have different views on the significance of commercial-gallery representation—that is, on whether such galleries are an influential part of artists’ success. And I do acknowledge that a critical eye needs to be placed on the entire ecosystem: museums, universities, board members, collectors, arts administration, staff, and so on, must all also be looked at for their lack of BIPOC representation. I knew that my research on commercial spaces was just a microcosm of the bigger picture—but it was something that I could achieve as an individual. That a similarly revealing survey of commercial galleries in Ottawa came out recently tells me I’m not alone in this scope and interest either.

Commercial galleries are businesses, but they are also members of the arts and cultural community. As such, they need to be held to a higher standard.

I didn’t have any expectations of the commercial galleries themselves once they saw the post. It simply felt like the right thing to do: unveiling the findings that confirmed what we intuitively knew. I do wonder, though: If galleries rectify their artist rosters to be more inclusive in the future, will their actions, moving forward, ever be seen as sincere? Personally, I want to be optimistic. I have to be optimistic because any other view is bleak and will wear me down. Ultimately, I hope any gestures that follow from galleries in the months to come are not short-lived and that they, instead, are part of a greater push toward real inclusivity for many who have always been held back. As Lauren Wetmore put it recently in a Momus podcast, “without a follow-up conversation, the implication of the solution is just, ‘Okay get those numbers up.’” And that’s not enough.

Here’s what some real change would look like: more BIPOC artists getting representation in commercial galleries, without it being an act of tokenism; more BIPOC artists having solo shows; and more galleries working with BIPOC collectors. And I’d love to see galleries giving back to the communities that they are often responsible for gentrifying. Commercial galleries are businesses but they are also members of the arts and cultural community. And as members of those communities, they need to be held to a higher standard of inclusiveness and promotion of equity than they have been previously.

At this time, all allies need to look at their own communities and industries for accountability. There are real reasons to feel optimistic. I have already seen the ripple effect on social media, but I hope to start seeing real change in real life. I have never before seen such solidarity in the Toronto arts community. And I do hope this momentum keeps going and growing. This is not a fad, this is not a temporary uproar. This is the boiling point. People want change, they demand it, and they won’t stop until this vision is fulfilled.

Updated spreadsheet published June 4, 2020, on

Updated spreadsheet published June 4, 2020, on