In the spring of 2016, I was gifted a ton of Joyce Wieland’s marble. The marble was a gift from Jane Rowland, who moved into Wieland’s house on Toronto’s Queen Street East shortly after Wieland passed away, in 1998. Joyce had originally bought the house to use as a studio, but after divorcing her husband, it became her full-time residence. Jane lived alone, using Joyce’s old bedroom as her office and Joyce’s studio as her bedroom.

When Jane moved in she took up residence with an odd assortment of objects that hadn’t been cleared out, rehomed or archived: a trio of wooden cassette racks, a pink moiré valance, hand-painted wallpaper trim and slabs of marble—all left in situ by Joyce’s next of kin. The marble was the heaviest of the remnants, and Jane would leave it exactly as she found it, which was where Joyce had left it: leaning on the second-floor banister and in a pile in the basement, slowly dimpling the earth with its weight.

*

In January 2019 I received an invitation from the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre to present work at “Re-Joyce: Wieland for a New Millennium” in Toronto. I proposed to do a performance called The Weight of Inheritance, which would chart my relationship to Joyce Wieland’s marble. Through a constellation of objects paired with spoken text, I mapped a sprawling, erratic and radiating cosmos—a queered chronology. There was a tall piece of marble, a length of moiré fabric on a roll, a wooden cassette rack (and blank cassettes that I asked the audience to write on), several large black-and-white printouts of raisins, a banner and a printed example of book-matched marble. There was also a pot of black ink and a brush with which I wrote out select words on a long, narrow strip of paper I’d wrapped around a concrete column. I started with infrastructure theorist Susan Leigh Star’s first sentence in her 1990 essay “Power, technology and the phenomenology of conventions: on being allergic to onions”:

“This is an essay about power.”

Living at the whim of chronic illness, capitalism (like, who isn’t!), patriarchy (duh!) and the foundations of a queer youth, I have no linear stories to chart. What has formed me, with my sticky fingers and porous mind, is a messy, sweaty, often uncertain inheritance. It isn’t biological (though I do love my mom and sister very much).

*

In 1971 Wieland opened “True Patriot Love” at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, when it was on Elgin Street, in the now-demolished Lorne Building. There are many things to appreciate and acknowledge as groundbreaking about Wieland’s signature show: live ducks waddling around, a brass band inaugurating the opening, collectively produced embroidery hanging on the walls, handmade patches on I Love Canada – J’aime le Canada calling out US imperialism and a collaborative sugar mountain sculpture Wieland made with Canada’s parliamentary restaurant chef. What stays with me, as an artist who makes, hangs, unfurls and drops banners, is the documentation of the banner that stretched across the building facade, emblazoned with the exhibition’s title in English and French. Not quite a banner-drop from the activists’ toolbox, but an embrace, a binding, a consensual bondage. I wonder how tight it needed to be in order to stay taut and remain legible. When does this kind of pressure maintain function and when does it create pain?

*

Does Joyce Wieland get enough attention? Has she gotten enough attention? Wieland gets enough attention compared to other women artists who get no attention. Wieland does not get enough attention compared to her artist ex-husband and other men working contemporaneously with her in both film and art.

*

On June 26, 2016, at 5:38 p.m., I received an email with the subject line “raisins over passion indeed.” It was from Jane Rowland.

Raisins Over Passion was a zine I made in 2012 loosely based on Joyce Wieland’s iconic work Reason over Passion (1968), as understood through a lens of my own chronic gastrointestinal illness. Jane had seen my raisin riff at Katharine Mulherin’s space No Foundation and gotten in touch.

We began corresponding and soon after I received an invitation to meet in person at Jane’s/Joyce’s home. I arrived with my partner Cait to a fairly nondescript three-storey brick row house. Before knocking

on the door, we took a moment to appreciate the shade of inky blue that Heritage Toronto and the Toronto Legacy Project had chosen for their “an-important-person-lived-here” plaques.

*

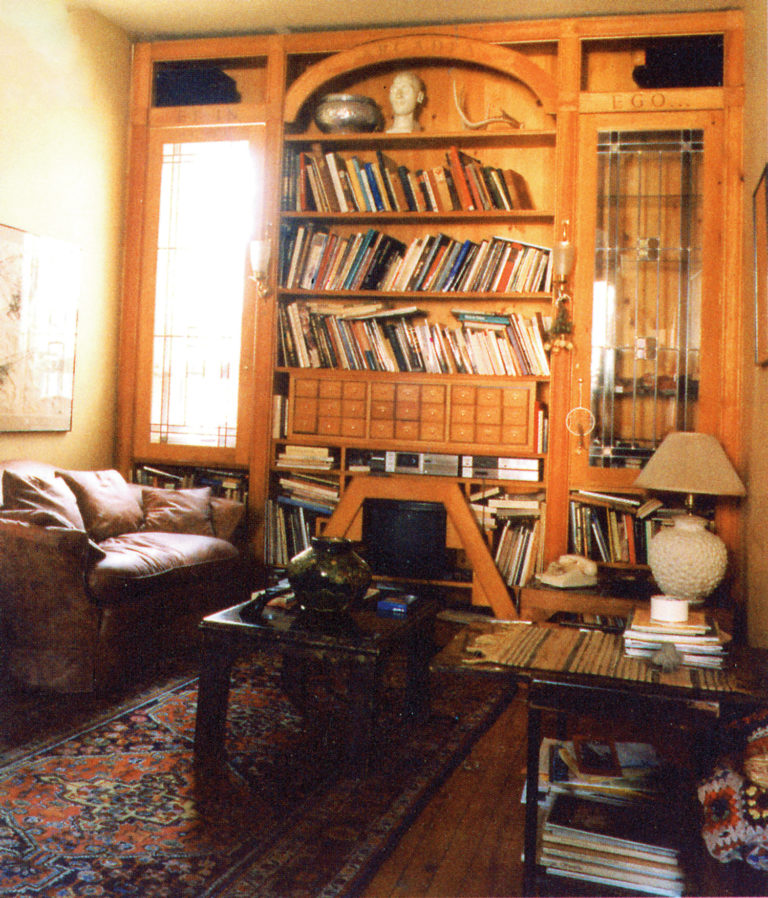

This house had a basement, a first and second floor, a third-floor attic and a backyard with birch trees. It had recently been taken on by a home-renovation television show. Jane mentioned this a few times as she walked us from room to room, pointing out the more garish decisions the gay television decorators had made: leopard-print carpeting, bathroom-floor tiles digitally printed with a stock image of light hitting the shallow water of a wading pool, pressed-tin ceiling tiles. She had experienced the very real financial and physical challenges of owning an old house, but explained her hesitation in making any changes to how Joyce had left it.

“There’s my chair / I put it there,” sings Diana Ross in her 1979 song “It’s My House.” The lyric will forever remind me of the aesthetic Cait and I met that day. As we followed Jane up the stairs to the second-floor landing, slabs of marble and piles of hooked rugs greeted us from their places, draped on and leaned against a banister and railing. Having once been deeply saddened by a girlfriend who “accidently” stepped on a drawing of mine while it was on the floor (among other precious objects), I understand this type of idiosyncratic feng shui Ross sings of and in which Rowland lived—and which I imagine Wieland lived in too. It is the “just so” aesthetic of a woman with no one to please but herself.

Hazel Meyer, The Weight of Inheritance (performance documentation), 2019. Courtesy Untitled Art Society. Photo: Katy Whitt.

Hazel Meyer, The Weight of Inheritance (performance documentation), 2019. Courtesy Untitled Art Society. Photo: Katy Whitt.

Hazel Meyer, The Marble in the Basement, 2020. Performance with Moe Angelos and Stephen Jackman-Torkoff. Courtesy FADO Performance Art Centre. Photo: Polina Tief.

Hazel Meyer, The Marble in the Basement, 2020. Performance with Moe Angelos and Stephen Jackman-Torkoff. Courtesy FADO Performance Art Centre. Photo: Polina Tief.

Inside Joyce Wieland’s house. Photo: Vincent Sharp. Every reasonable effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders to obtain permission to reproduce this image. If you have any queries please contact editorial@canadianart.ca.

Inside Joyce Wieland’s house. Photo: Vincent Sharp. Every reasonable effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders to obtain permission to reproduce this image. If you have any queries please contact editorial@canadianart.ca.