Ed Mirvish was a Toronto legend. His discount store, Honest Ed’s, was more than a bargain department store. To many Torontonians it was a place of family, of entertainment and of adventure—a widely accessible one at that. When the store marked its closure with a weekend celebration in 2017, with plans already afoot to turn the land into a multi-tower real-estate development, thousands of Torontonians lined up to bid farewell to the store and what it stood for—things like annual free turkey giveaways and a dozen dishcloths for a dollar. The site will house approximately 50 new buildings, some of them quite tall, with the entire site offering roughly a thousand rental apartments plus a variety of retail spaces.

About a year after the closure of Honest Ed’s and its subsequent demolition, a series of three murals appeared on the hoarding surrounding the construction site that’s now in its place. A 2014 municipal bylaw requires that at least 50 per cent of the surface area of construction hoardings accessible to the public must be used for community art—so the murals are no big surprise. But when the developer behind this new Mirvish Village development is Westbank, they become part of a trend in which art dovetails with gentrification—or what some artists have called “artwashing.”

In recent months Westbank has also presented the 2016 architectural installation, Serpentine Pavilion, on Toronto’s King Street West to promote a new condo development. And just over a year ago, Westbank faced backlash for “Fight for Beauty,” an exhibition they organized near the luxury Fairmont Pacific Rim hotel they built in Vancouver. From small murals to huge installations, Westbank—like many other developers—has leveraged public art as a tactic to appear more ethical, considerate and community-focused in the midst of accusations of gentrification. But that strategy hasn’t always worked out as intended.

—

The pitch for this development replacing Honest Ed’s, then, is framed as a kind of sustainable, creative urban village. But who is this village for, exactly?

Maybe it’s best to start small. One construction hoarding where Honest Ed’s used to stand presents two horizontal digital collages titled To dwell is to leave traces by Toronto artist Jessica Thalmann. Her collage stitches together archival photos of houses in the area, providing an architectural overview of the neighbourhood’s transforming history since 1948. Thalmann cuts, collages and digitally folds the images into multicoloured polygons so that their contents represent “the traces, debris and discarded remnants of the city,” accessing the past in order to anticipate the future.

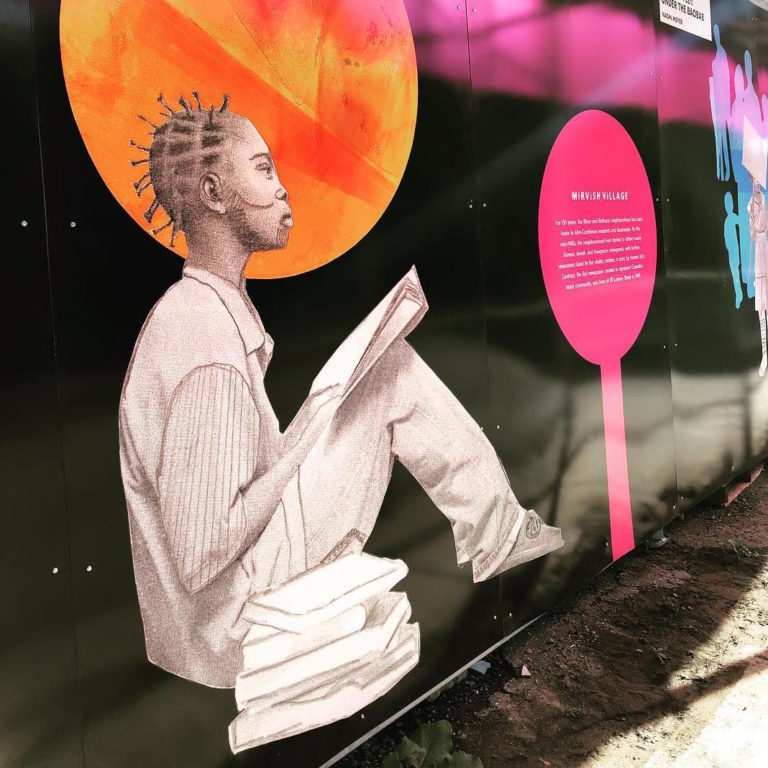

Another nearby hoarding supports Naomi Moyer’s mural Sit at My Feet: Under the Baobab, a compilation of sketches of Black folks who have settled in the area for more than 150 years. Moyer’s sketches show people going to the barbershop, children playing, folks at community protests and pages of Contrast newspaper—a publication for Toronto’s Black community founded near Bathurst and Bloor in 1969. Each drawing is a glimpse into the lives that used to be, have been or still are in this neighbourhood. Installed next to a rendering of the forthcoming Westbank apartment towers, they made me wonder whether there would be room for the continuation of these working- and middle-class Black communities in the new Mirvish Village development.

According to other panels nearby, the new Mirvish Village will integrate the “historical streetscape with low and mid-rise buildings, micro towers, 24 restored heritage buildings, pedestrian laneways and a public market featuring food entrepreneurs, artisans and daily live music.” On another hoarding panel, Westbank CEO Ian Gillespie acknowledges that the community’s history is rich, diverse, inclusive and, perhaps most significantly, that it’s been characterized by 65-plus-years of affordability. “Honest Ed’s,” Gillespie states, “brought together people from all walks of life. It catalyzed collective memory-making.” Not mentioned in this description is the fact that the City of Toronto defines affordable housing in Mirvish Village, and elsewhere, in relation to Toronto rental market prices—a value which is already exorbitant, and expected to continue to rise. The City of Toronto is trying to secure 20 per cent of the apartments in the neighbourhood for affordable housing, but the most recent documents indicate they have secured less than half of that from Westbank so far. Using this municipally legislated guideline, rent on a “deeply affordable” one-bedroom in Mirvish Village would still cost $962 per month.

The pitch for this development replacing Honest Ed’s, then, is framed as a kind of sustainable, creative urban village. But who is this village for, exactly? This question becomes more pressing when reflecting on the former residents and community members depicted in Thalmann and Moyer’s artworks, as it is doubtful that they could afford to rent the new housing units being constructed just a few feet behind the artworks in which they are depicted.

Part of the hoarding mural by Naomi Moyer at the Mirvish Village construction site. Photo: Mirvish Village Instagram.

Part of the hoarding mural by Naomi Moyer at the Mirvish Village construction site. Photo: Mirvish Village Instagram.

Part of the hoarding mural by Jessica Thalmann at the Mirvish Village construction site. Photo: Mirvish Village Instagram.

Part of the hoarding mural by Jessica Thalmann at the Mirvish Village construction site. Photo: Mirvish Village Instagram.

—

Founded in 1992, Westbank is a development firm known for luxury residential and mixed-use projects. Headquartered in Vancouver, the firm has a history of integrating art into project campaigns. In 2017, Westbank produced a pop-up exhibition titled “Fight for Beauty,” which featured work by a roster of Vancouver and international artists and architects inside a custom-built, brightly coloured tent accentuated with magenta—Westbank’s corporate colour. The exhibition was an opulent display of questionable curatorial strategy—if any such strategy existed at all. Montecristo writer Imogen Jefferies describes the experience inside the exhibition: “the massive, canopy-like structure is lined from wall to wall with rich, dark wood floors and warm, inviting lighting. At the entrance, visitors can grab an earpiece and listen to a 58-minute tour narrated by Gillespie, floating amongst the maquettes of past and future buildings on display and learning about Westbank’s goal in creating multi-purpose urban spaces alongside renowned architects like Kengo Kuma and Bjarke Ingels.” The experience appeared to be nothing but an elaborate sales presentation.

In this showcase Westbank architectural maquettes were on display with works from international artists, like Zhang Huan’s sculpture Rising, Martin Boyce’s Lantern Chain and Omer Abel’s glowing trees titled 16.480. Other notable artists in the show were Fred Herzog, Stan Douglas, Shane Koyczan and Douglas Coupland. Additionally, Gillespie put vintage couture pieces from his personal fashion collection on display, ranging from Alexander McQueen to Yves Saint Laurent.

Gillespie’s heavy-handing over the exhibition, not to mention his narrated audio guide, portrayed him as a tastemaker, with a subtext (“Mr. Gillespie knows good art, good design and good fashion, so buy in now.”) The “fight” for beauty here was understood as Gillespie’s alleged struggle to put up “beautiful” condos despite frequent pushback from communities and governments.

Understandably, “Fight for Beauty” was not well-received by the wider Vancouver art community. Maryse Zeidler, in a report for the CBC, remarked how the company framed the exhibition as a philanthropic project where beauty was re-contextualized as something accessible; but the community where the exhibition took place denounced it as artwashing, saying that Westbank’s developments made urban space inaccessible to artists and others of comparable incomes. These artists pointed out that arts and culture were being used as a Trojan horse—under the guise of neighbourhood revitalization—in order to displace lower- and middle-income residents and extract profits from the wealthy.

Accordingly, a group of Vancouver artists, curators, writers, activists and community organizers formed a coalition to shift attention from Westbank’s artwashing exhibition to the struggles they experienced in their own fights for beauty in Canada’s most expensive city. Vancouver-based activist Melody Ma created a parody of the exhibition website and called it “The Real Fight for Beauty.” The website documents protest actions in the community and offers press materials that provide deeper insight into Westbank’s intentions. The website states that Westbank is “co-opting the arts for PR purposes, while artists are being economically and physically displaced in Vancouver due to unaffordability perpetuated by real estate development companies”—a statement just as relevant to the art community in Toronto where Westbank is expanding.

The sales pitch on King West is that viewers would not simply live in a building—they would inhabit an art piece.

—

Torontonians should consider Westbank’s “Fight for Beauty” campaign and the associated backlash right now. During a promotional presentation at the Roy Thompson Hall in October 2018, Gillespie again claimed to be a cultural producer. That presentation had to do with a Westbank project in Toronto, the KING development near King Street West and Spadina Avenue. The talk featured the architect Bjarke Ingels along with artist Douglas Coupland—both of whom were included in the “Fight for Beauty” exhibition.

To promote the KING Toronto development, Westbank has used art in yet another way—namely, by bringing Ingels’s Serpentine Pavilion, the 2016 architecture commission by The Serpentine, to Canada . This makes Toronto the location of pavilion’s first international appearance after leaving Hyde Park in London two years ago. In Toronto, the pavilion housed a Westbank exhibition titled “UNZIPPED,” featuring maquettes for developments across North America that Westbank and Ingels’s architectural firm, BIG, are collaborating on. Despite being advertised as the main attraction, the pavilion has been deployed here as a promotional vehicle to get visitors immersed in Westbank’s architectural “greatness,” and to offer a taste of the KING residences—a taste to drive appetite, and ultimately boost sales.

Admittedly, the KING condos architectural rendering mirrors much of the Serpentine Pavilion’s tectonic elements, with cubical units growing vertically while also spreading above some to-be-preserved heritage buildings on the lot. According to renderings, each unit would have its own terrace of cascading greenery, forming an organic terrain of concrete and trees sprawling over Toronto’s skyline. (No wintertime renderings were offered.) Similar to the strategy of “Fight for Beauty” in Vancouver, KING Toronto’s renderings and “UNZIPPED” have been mesmerizing and Instagram-worthy, heightening appeal to future buyers. The sales pitch here is that viewers would not simply live in a building—they would inhabit an art piece.

Renderings of the Westbank development KING, displayed at UNZIPPED Toronto. Photo: Westbank Instagram.

Renderings of the Westbank development KING, displayed at UNZIPPED Toronto. Photo: Westbank Instagram.

KING Toronto Courtyard rendering. Photo: Westbank Instagram.

KING Toronto Courtyard rendering. Photo: Westbank Instagram.

—

Despite possessing many architectural merits, the context in which Ingels’s Serpentine Pavilion has been presented in Toronto raises concern about the intention of Westbank as the exhibitor and eventual developer of the KING project. With pre-launch prices for KING Toronto condos starting in the mid $700,000s, it seems that as a self-proclaimed culture producer, Westbank promotes art that is accessible only to those who can afford the price tag.

The futuristic optimism of “UNZIPPED” and KING Toronto contrasts with the nostalgia on view at Mirvish Village. Interestingly, messages at both exhibitions avoid engaging with the present. Is this a tactic? The company’s way of distancing itself from the immediate problems of gentrification, neighbourhood displacement and unaffordable housing?

It must also be acknowledged here how city legislation is often complicit in developer interests. In other words, it’s not just Westbank that is the problem, whether in Vancouver, Toronto or elsewhere. The mechanisms of land-development power matter, as do these displays of “community-improving” art— and the wave of popular support generated through Insta-friendly sketches help developers make cases to the city for zoning variances, height exemptions and more.

Perhaps the thorniest issue of all for an artist or art writer in considering these issues and artworks is the question of the creative work itself. When an artwork draws inspiration from and presents content about communities affected by real-estate development and then frames such content as a celebration of history, the artists must try to maintain their integrity and criticality by making space for viewers to reflect on the complexity of gentrification. This has created exclusive access for certain interest groups while removing access from others. In this context, Moyer and Thalmann’s murals at Mirvish Village, Ingels’s Serpentine Pavilion at King West or artworks by Coupland, Douglas, Koyczan and Herzog in “Fight for Beauty” could be seen as lip-service to the developer and completely subsumed by Westbank’s desired image of being a “culture producer.”

How much are the artists to blame? Not very much, I think. If I were Moyer or Thalmann, I would take the commission, too. It is a known fact that artists’ careers in Canada are precarious and unsustainable—few artists and cultural workers can afford to say no to any money.

Maybe the uneasiness I feel in seeing Moyer’s and Thalmann’s murals wrapping around the construction site of the incoming Mirvish Village has a different kind of value—value in the way they compel viewers, me included, to actually question the social commitment of Westbank and the complicated position of art and artists amid the complexity of neo-liberal real-estate development.

This article was corrected on February 11, 2019. The original incorrectly spelled Zhang Huan’s name as “Zhan Huang.”

A rendering of Westbank's Mirvish Village development in Toronto. Via Mirvish Village.

A rendering of Westbank's Mirvish Village development in Toronto. Via Mirvish Village.