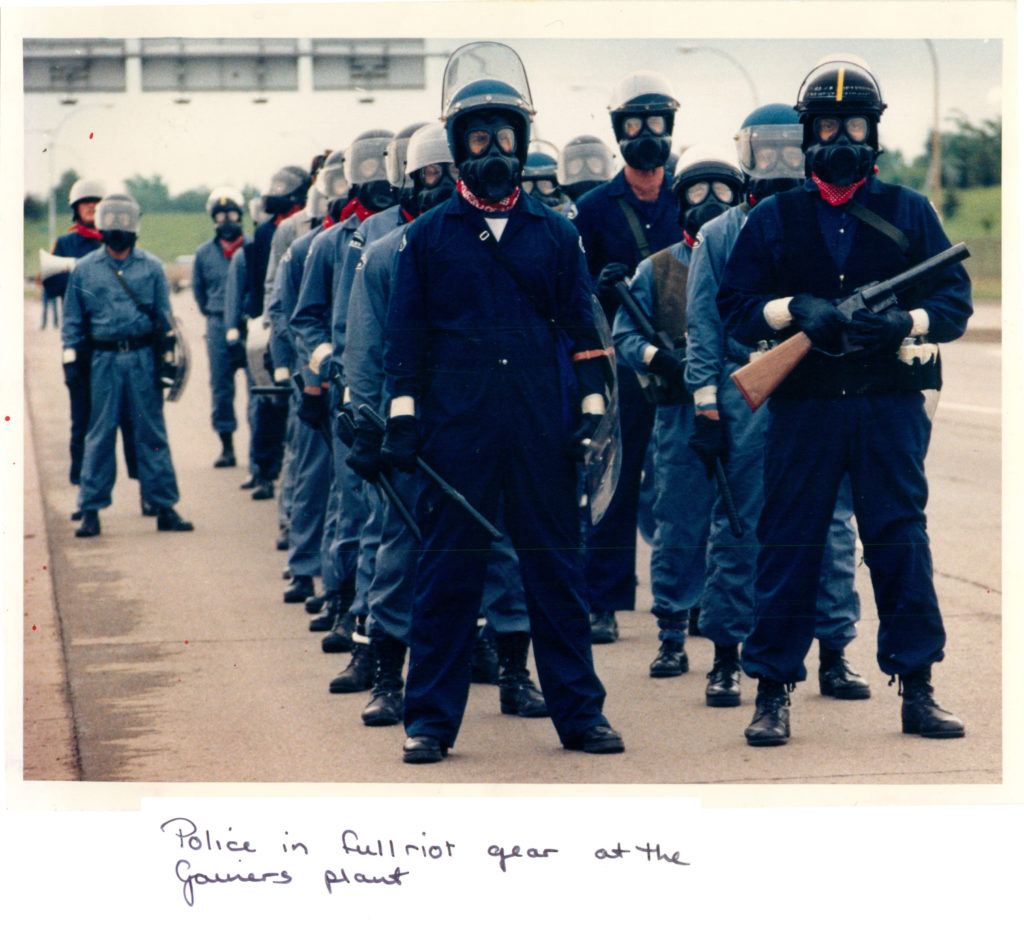

I’ve been thinking about this issue’s call for “writing and projects that explore particular histories, curiosities, interests and obsessions.” It got me thinking about where curiosity ends and obsession begins. What instantly came to mind were two photographs I saw when I was a kid and that I’ve never quite been able to shake—from our local paper, the Edmonton Journal. I suspect that’s when I first saw them, I don’t exactly remember—I was 11 at the time. It’s hard to tell how much of my memory comes from that precise moment and how much has been built up from stories shared by others or my own repeated examining of the history. Either way, the images have always haunted me, and I see a lot of my work, research and overall interest in visual culture as influenced by them. The photographs show the 1986 Edmonton police response to labour strikes by Gainers meatpacking plant workers.

I’ve retold this history a number of times, often in long, rambling emails to friends as an addendum to conversations where I mentioned it in passing. The act of writing these emails—and especially the time I’ve spent sifting through links and images to share along with them—has also shaped my memory of the event itself. It’s hard for me to know now which parts I actually remember from my childhood and which have been siphoned off internet searches. Upon each revisitation, I learn more, forget more and then learn more about the history all over again.

However it is that I came to first see these images, they have stuck with me going on decades now. I found them terrifying, especially as a young kid, and their chilling aesthetic seemed to me only explainable as being from the future—or, really, from science-fiction movies about the future. In hindsight, the impact these images had helps explain my gravitation toward not only sci-fi movies, but those framed within a story of resistance in particular. I love films in which citizens fight back against fascist states (always maintained by fascist cops) that have run their fantastical future world into the ground. Of course, there’s nothing fantastical about the idea of fascist cops—their presence in film comes straight from reality.

Robert Duvall in THX-1138, 1971. Courtesy Picturelux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

Robert Duvall in THX-1138, 1971. Courtesy Picturelux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

There’s a blurry line between the aesthetics of film and real life, and these images always seemed to me such a great example. I mean, stop for a second and consider that they document real-life events in 1986. A quick search reveals that only two years later, in 1988, protesters in New York’s Tompkins Square Park were met by cops similarly armed with batons and face shields, but their uniforms were far from the overtly fascist vision that met Edmonton protestors just two years earlier. To me, the police response in Edmonton to the Gainers strike looks much more dystopian, more akin to the faceless android police from George Lucas’s THX 1138 (1971) than to their brethren from New York. Maybe whoever styled those cops’ riot gear in Edmonton back in the ’80s had been influenced by the film. Maybe, as they ordered those blue coveralls in bulk, they imagined a dismal future like the one from THX 1138 and projected those faceless android cops into reality.

I’ve been thinking about how, after I first shared the Gainers strike photos with the editor of this piece, she mentioned RoboCop (1987)—not only the ways police were imagined in the film, but also the many articles published in its wake connecting the story to the rise of the neoliberal state. One of these think pieces, by Keith Orejel, responds to the 2014 remake: “At the heart of RoboCop is a cautionary tale. The movie warns against the inherently corrupting nature of public–private partnerships.” It occurs to me now that these images of Edmonton police might perfectly capture where neoliberal fantasy meets reality—a state striving for the punishing control of RoboCop, but on a neoliberal budget.

Since 2020 began, I’ve also been thinking a lot about the movies I grew up watching in the 1980s and ’90s—and how they instilled in me this ability to recognize (maybe I mean anticipate) the signs of a society on the brink of collapse. I’ve always gravitated toward horror and sci-fi genres, and that time period in particular crafted some truly influential works, in a pop-cultural sense. For those growing up when I did, movies represented the world in a specific way: while we witnessed the rise of neoliberalism IRL, they predicted for us how it would end. Thirty-some years later, here we are.

Edmonton Police at the Gainers plant, 1986. Material republished with the express permission of Edmonton Journal, A Division of Postmedia Network Inc.

Edmonton Police at the Gainers plant, 1986. Material republished with the express permission of Edmonton Journal, A Division of Postmedia Network Inc.

I remember my parents and other grownups frequently speaking about the Gainers strike, how terrible it was. The man at the centre of it all was Peter Pocklington, and I remember my parents saying his name like it was poison. They still do—it makes it difficult to know if my introduction to the events surrounding the strike happened in real time or after the fact. When I asked my mom about it recently, all she said was, “Yeah, it went on for a long, long time,” then sighed and walked away. The internet tells me it went on for six and a half months.

It’s a convoluted story.

Gainers was a meatpacking plant in Edmonton near the end of the city’s heyday as Western Canada’s hub for the industry. At the time the Gainers strike photos were taken, the plant was owned by Pocklington, an entrepreneur, former Progressive Conservative Party leadership contender and “vocal advocate of free market capitalism,” according to a number of online biographies. Pocklington is also known (out here, at least) as “Peter Puck” because he is most famous (out here, at least) for owning the Edmonton Oilers during their “dynasty years,” and perhaps even more famous for trading a tearful Wayne Gretzky to the Los Angeles Kings in 1988. I learned later that he owned a number of other sports teams, but his role with the Oilers is especially important to the retelling of the Gainers story, partly because the team is so influential in the social fabric of the city, and partly because its growing success under Pocklington’s ownership became a sticking point for Gainers workers demanding fairer pay.

In 2014, for the 30-year reunion of the Oilers’ 1984 Stanley Cup–winning team, an Edmonton crowd gave Pocklington a standing ovation, an important reminder of just how prone people are to forgetting collective histories and a great example of the ways we pick and choose which histories to remember. (This event so utterly pissed me off that I still scream on the inside whenever I recall it.)

Peter Weller as RoboCop, 1987. Courtesy Everett Collection/AF Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

Peter Weller as RoboCop, 1987. Courtesy Everett Collection/AF Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

Before knowing the details of the strike, it is important to know the backdrop of Edmonton at the time. The year 1986 was the peak of the ’80s global oil glut—when oil prices collapsed and Alberta, seemingly forever trapped by its reliance on the unstable oil industry, faced a steep recession. At the time, strikes broke out in a number of sectors across the province. Amid the rise in neoliberal policymaking, including the privatization and deregulation that had already begun to take a strong hold on many industries, workers struggled to maintain the protections they relied on. Edmonton’s economy has always been—and continues to be—at the whim of the boom-and-bust oil industry, but the ’80s marked a peak of this instability.

At the time of the dispute, Gainers was one of the largest meatpackers in the country. Before the 1986 strike, Pocklington argued that the Alberta Pork Producers Marketing Board (now called Alberta Pork), the nonprofit that from 1969 through 1996 served as the “single-desk seller to market all pigs in Alberta,” had too much power. Convinced that his profit margin was undercut because the board was fixing hog prices—a charge, by the way, they repeatedly denied—Pocklington went so far as to launch a media campaign against the organization in 1985.

When the Gainers collective agreement expired in 1986, Pocklington insisted that high hog prices meant he needed to keep operation costs low. As a result, Gainers management enforced a starting-wage cut of more than 40 per cent and threatened workers’ pensions. Anticipating a strike, Pocklington ran ads for replacement workers and brought in strike-breakers, or “scabs,” from Quebec. On June 1, 1986, 1,080 employees—members of the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 280-P—took strike action. Further fuelled by the employment of temporary workers and (out-of-province) scabs, the strike quickly turned into one not only about wages and pensions, but also about the jobs themselves, transforming into volatile confrontations. A third of the Edmonton police force was brought in to manage the situation. Strikers attacked the police-escorted buses transporting scabs across picket lines, thousands protested in support of the workers, production at the plant dropped sharply and Gainers products disappeared from shelves. The meat that did make it into stores was continually sabotaged by shoppers who covered displays with “Boycott Gainers” stickers before items could be sold. Front yards were covered in lawn signs speaking out against the company and encouraging people to boycott their products. Gainers became the most unpopular brand in town—a sentiment that spread across the country.

I wonder how my work would be different if these images from 1986 didn’t continue to haunt me, if our collective visual culture wasn’t constantly having to imagine futures bound by the injustices felt across our experience.

The strikes finally ended in December of that year, after Premier Don Getty stepped in and handed Pocklington a sizeable provincial aid package (most sources confirm the package amounted to roughly $67 million, a combination of loans and other assistance) upon agreeing to rehire striking workers at a two-year wage freeze followed by a small raise, and with pensions intact. When Gainers failed to make loan repayments three years in a row, the Alberta government took over the company. The government ran Gainers for four years at a loss and eventually sold the company (also at a loss). Peter Pocklington still owes the province of Alberta $13 million—and more than 30 years later, lawyers for the province say they continue to attempt to collect it. I wonder if they asked him about it in 2014 when he received that standing ovation (I’m screaming).

I’m not surprised that Edmonton hockey fans would praise the man who, in their eyes, brought them the game, while completely ignoring the damaging precedent he set in Canada through his refusal to recognize pattern bargaining and adhere to collective agreements of labour unions (a tactic that continues across industries to this day), or even just the money he owes the province. I guess it’s also likely that some of those fans were the very cops from the Edmonton Journal photos, or maybe their kids. I’m sure they see Pocklington differently than I do. I get that. But I can’t stop thinking about this sense of collective forgetting, and how tied up it is with so many other issues we face. What does it mean for a society to prop up those who in any popular movie would be quickly understood to be the utmost of villains? What does it mean that we as a city ignore the harm Pocklington caused workers? Considering the damage of our current provincial government’s cruel austerity budget, that $13 million Pocklington owes could really come in handy now.

It’s impossible to remember this story without considering the links to worker disenfranchisement at meatpacking plants throughout the current pandemic. The Cargill meatpacking plant, part of a private American conglomerate, had almost 1,000 employees test positive for COVID-19 at its High River location this past spring. In July, a class-action lawsuit was filed against the plant in connection to the outbreak, alleging not only that the company knew the lack of protective measures would result in harm to its employees and their families, but also that they lured workers back from self-isolation, putting employees further at risk. To date, more than 1,500 cases of COVID-19 have been tied to Alberta’s Cargill plants—along with three deaths. That many of the 2,000 employees are immigrants and temporary foreign workers and thus more at risk for manipulation from management reminds me that the worker protections lost during the Gainers strike in 1986 have had long- lasting impacts on workers’ rights through the years.

In hindsight, the impact these images had helps explain my gravitation toward not only sci-fi movies, but those framed within a story of resistance in particular.

Thinking back to the public support Gainers workers received throughout their six-month strike, I can’t help but wonder where that same support is for meatpacking workers now. They’re literally facing sickness and death at the hands of the companies they work for, all for profit’s sake; in the case of Cargill, the corporation reported net earnings of US$2.56 billion in 2019.

Since the pandemic began, numerous plants across the country have had outbreaks. Working conditions at meatpacking plants have always been dangerous, but the push to remain profitable at the expense of workers has never been more visible than during the pandemic. Where was the boycott on meat processed at the Cargill plant? I can’t ignore the role racism plays in this: that the majority of workers in today’s meatpacking plants are people of colour, many new to the country, taking on jobs that have seen security and compensation degraded over the years, is related. Of course, the reality of globalization means that all these issues are tightly woven together and difficult to tease apart. But the example of Pocklington’s Gainers surely points to the beginning of where we find ourselves now.

Since the Gainers strike, Pocklington has been charged for fraud in the US numerous times, with little consequence: in 2009 he was charged for bankruptcy fraud; in 2013 he failed to pay restitution of US$5 million in a securities fraud case in Arizona; he was charged with securities fraud again in California five years later. Despite this, he made Canadian headlines in 2018 as he sought out investors for a new venture: a hydroponics cannabis facility in California. Don’t get me started. We knew the legalization of marijuana would see crooked rich white guys take over the industry for a product whose criminalization for decades reprimanded Black and marginalized citizens (many of whom are still in prison). Once again, looking closer at Pocklington reveals so many of the issues in our unequal and unjust system.

I really could go on. I just got lost down another internet rabbit hole. I’m thinking again now about this question of where curiosity ends and obsession begins. I wonder how my interest in this history could be perceived less as obsession and more as curiosity if only we remembered our collective experiences more acutely. As an artist, the obsession drives me, but a lot of the time, I wish it didn’t. I wonder how my work would be different if these images from 1986 didn’t continue to haunt me, if our collective visual culture wasn’t constantly having to imagine futures bound by the injustices felt across our experience.

Edmonton Police at the Gainers plant, 1986. Material republished with the express permission of Edmonton Journal, A Division of Postmedia Network Inc.

Edmonton Police at the Gainers plant, 1986. Material republished with the express permission of Edmonton Journal, A Division of Postmedia Network Inc.