I’m getting a storage locker in Vancouver to tide me over between shifting studio and apartment sublets, and to consolidate my items guarded in the closets, basements and storage lockers of kind friends. For me, 2017 has been a year of negotiating spatial precarity—three months here, six months there, packing and unpacking boxes, and moving piles.

Looking back at my favourite art experiences of the year, I’m aware that they all, too, have highlighted, overcome or circumnavigated issues of storage and the challenges of Vancouver’s housing crisis.

An installation view of Jessica Bell’s exhibition at Unit 17. Courtesy Unit 17. Copyright the artist. Photo: Pongsakorn Yananissorn.

An installation view of Jessica Bell’s exhibition at Unit 17. Courtesy Unit 17. Copyright the artist. Photo: Pongsakorn Yananissorn.

Unit 17 opened in January in the iconic wedge-shaped building where Kingsway meets Main Street. The new commercial gallery was named for this first venue—a narrow corner unit on the second floor, with a partial wall that smartly obscured its office without blocking its windows (a certain satisfaction comes with witnessing the clever ways in which ordinary rooms are made suitable for showing art). Without counting its offsite projects, Unit 17’s exhibitions have spanned three separate locations, most recently a storefront building on West 4th Avenue. More than a former site, the name is now associated with the energetic adaptability with which the gallery has met venue-related obstacles in its inaugural year.

The second and final exhibition in the Main Street space, before the gallery abruptly moved, was a solo show by Vancouver-based artist Jessica Bell. While all of Unit 17’s programming has been strong, the succinct gestures of Bell’s exhibition are vivid in my mind. The works came out of a residency she completed in spring of 2016 at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, in North Adams, Massachusetts, which was historically a mill town with an emphasis on textile manufacture. Mass MoCA itself occupies what was once the Arnold Print Works complex.

With simple muslin, fabric remnants and discount clothing as their central materials, Bell’s works in this series form mental passageways between places and times. Sourced in North Adams, all of the cloth materials travelled to Vancouver by suitcase, and the works seem to imply further transport. Softlines (landscape) (2016) features 79 pairs of hand-dyed men’s, women’s and children’s dollar-store socks, vacuum-sealed into a leaning storage bag, as though positioned to be easily scooped up, and carried off.

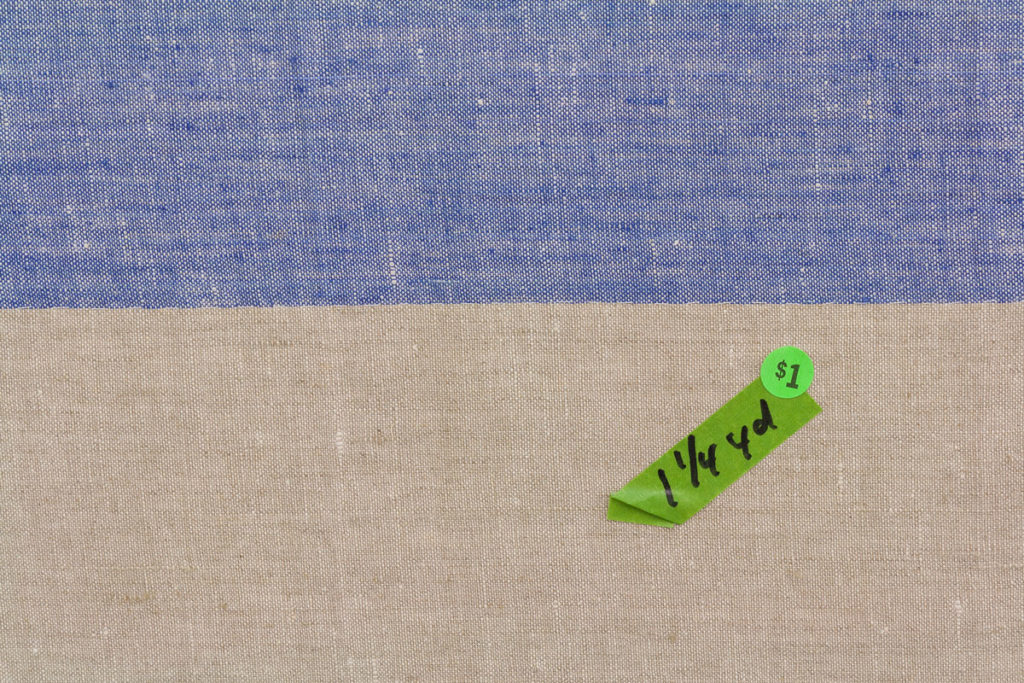

Detail of Jessica Bell’s work at Unit 17. Courtesy Unit 17. Copyright the artist. Photo: Pongsakorn Yananissorn.

Detail of Jessica Bell’s work at Unit 17. Courtesy Unit 17. Copyright the artist. Photo: Pongsakorn Yananissorn.

Bell configures ordinary materials with such restraint that they are defamiliarized, achieving other-worldly associations. The stark assemblages of rummage sale finds and craftwork motifs resist sentimental reading, with certain works seeming to articulate science fictions. Seed Work (2017) is a fabric remnant on quilted and stretched muslin, with a short length of green masking tape adhered central-frame, bearing hand-written yardage and a one-dollar price tag. With the found material stretched in landscape orientation, its horizontal stripes evoke an interrupted transmission, or flickering screen.

Similarly suggestive of space gadgetry, or ghostly conveyance, Commonwealth (v-neck, mock neck) (2016) and Commonwealth (pants) (2016) consist of hand-dyed discount clothing sandwiched between two layers of stretched muslin. They are visually confounding, with bodily shapes faintly visible, as though paused mid-teleportation.

Lightness of heart and firmness of foot (2016) is an inflatable dunnage bag with a yo-yo quilted cover. An archive of material research and a marking of the passage of time, its bunched muslin shapes represent each dye bath undertaken by Bell during her residency. I envision the performance of the sculpture’s deflation, after which it could be tidily tucked away out of sight come exhibition close—no storage locker required.

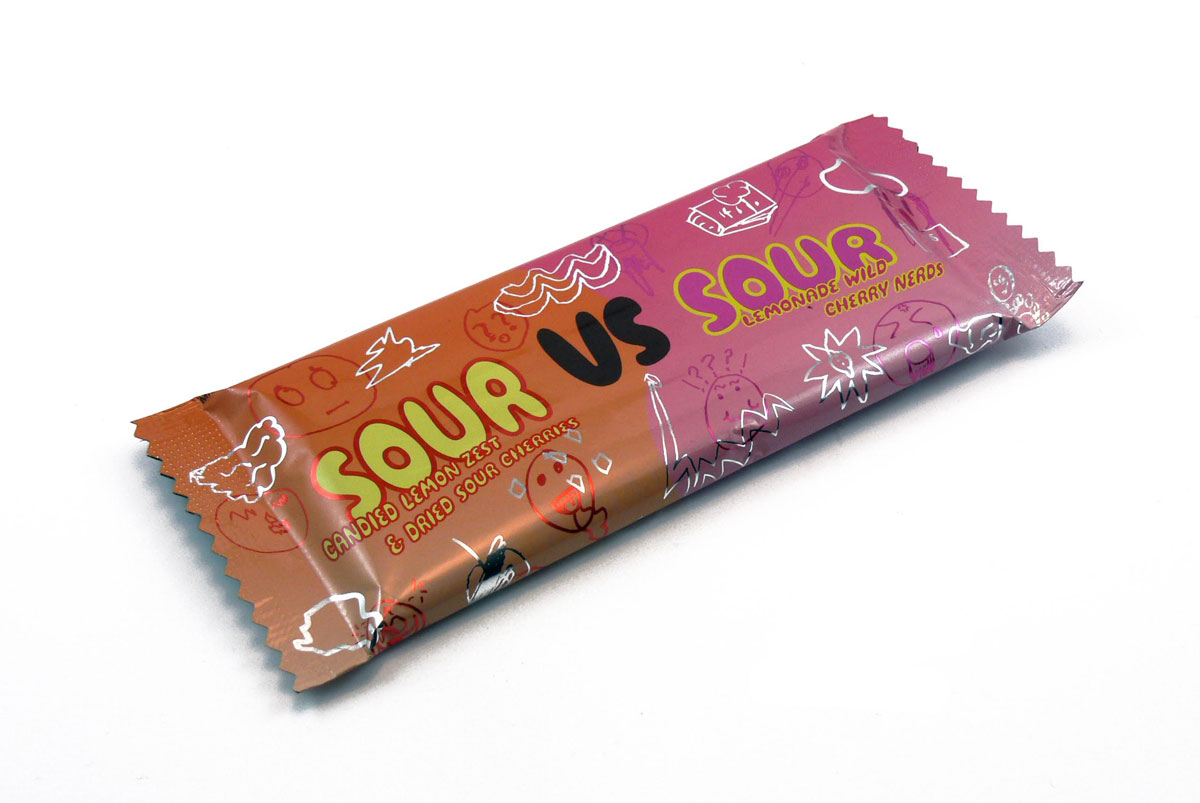

The SOUR VS SOUR chocolate bar plays off of a child-adult culture clash, and integrates social enterprise as well. Photo: Courtesy Hannah Jickling and Helen Reed.

The SOUR VS SOUR chocolate bar plays off of a child-adult culture clash, and integrates social enterprise as well. Photo: Courtesy Hannah Jickling and Helen Reed.

Also transparent regarding the impermanency of its gestures, Big Rock Candy Mountain is a multi-year engagement between artists Hannah Jickling and Helen Reed and students at Queen Alexandra Elementary School in East Vancouver. Curated by Vanessa Kwan and produced by Other Sights For Artists’ Projects, the initiative is described in various promotional texts as “a flavour incubator and taste-making think-tank.” While its facilitated dialogue occurs primarily between visiting artists and classroom students—who participate in numerous talks, workshops, experiments and fieldtrips—Big Rock Candy Mountain has extended its discourse to a broader public, notably through the edible artist edition SOUR VS SOUR.

After three months of exploration and research into divergent tastes with a grade 3/4 class, the artists worked with East Van Roasters—makers of organic “bean-to-bar” chocolate—to create the 58-gram individually wrapped bars. Produced locally in small batches, the editions have been available for purchase throughout the year at various art institutions and online. Taking cues from kid-targeted candy marketing, SOUR VS SOUR refers to the meeting of lemonade wild cherry Nerds, dried sour cherries and candied lemon zest, embedded into the underside of a 70% Madagascan chocolate bar, creating opposing sides of synthetic versus natural flavours. The tagline on the playfully garish foil wrapper reads “battle in a bed of bitter chocolate.”

Importantly, through its foray into confectionery preferences, the youth-empowering SOUR VS SOUR contemplates adjacent concerns—teaching, for example, about single-origin, fairly traded cacao beans while engaging with issues of Vancouver homelessness. East Van Roasters is a social enterprise of the PHS Community Services Society, a non-profit organization that provides housing and advocacy to individuals in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Located below the Rainier Hotel, a women’s-only housing project, the chocolate and coffee maker provides employment and job training for hotel residents.

SOUR VS SOUR is delicious and symbolic of the lively exchange between adults and kids instigated by Big Rock Candy Mountain’s inventive approach to public art. The project has proven that socially engaged practices can be funny and accessible while exploring new material approaches and furthering contemporary art dialogues. Jickling, Reed and Kwan are adept at selecting and combining playful, political and educational elements in a way that feels relevant and exciting. Next up: a chewable edition representative of recent explorations of gum as both a commodity and a sculptural medium.

View of “Kitchen Midden” at Griffin Art Projects. Photo: SITE Photography.

View of “Kitchen Midden” at Griffin Art Projects. Photo: SITE Photography.

Irrefutably joyful and a clear 2017 standout, “Kitchen Midden” was an exhibition of artworks, artifacts and objects culled from the private collections of nearly 100 artists based in Vancouver and its outlying areas. Presented at Griffin Art Projects in North Vancouver, it was curated by artists Anne Low and Gareth Moore, and was equally their installation—easily identifiable as aesthetically akin to their recent individual practices. (Additional to realizing this project, Low and Moore each presented notable solo exhibitions in 2017: Low’s materially mesmerizing “Witch With Comb” took place at Artspeak, while Moore’s “Bullae” encompassed a string of performances and an adjoining installation, together touted as “a series of sonic emanations” at Catriona Jeffries.)

Often requiring dedicated and costly spaces complete with temperature and humidity controls, institutional collections live in crates and drawers—their artworks and objects are snug between rigid foam segments, hidden under black felt cloths or bubble wrap, away from the light of day. They’re surveilled, and displayed behind glass or secured with steel brackets. By contrast, “Kitchen Midden” presented objects and artworks liberated from the conservational constraints typical to archives. The wide assortment of exhibited items—from feathers to photographs, textiles to ceramics, knick-knacks to furniture—were open to the room (and to potential prodding by viewers), displayed on sculptural platforms, draped over doorways and partitions, and constellated on the gallery walls.

View of “Kitchen Midden” at Griffin Art Projects. Photo: SITE Photography.

View of “Kitchen Midden” at Griffin Art Projects. Photo: SITE Photography.

The arrangements positioned artworks proper—The Circle of the Thieves (1827) by William Blake, or Sperm Whale, Teeth (1973) by Liz Magor—as equals next to artists’ personal and often strange collections: a stack of yogurt lids belonging to Kelly Lycan; an assortment of Marian Penner Bancroft’s rocks; or Khan Lee’s jars of cigarette ash. A paper guide provided some details and distinguished the array of known contemporary and historical originals from items with unknown makers, emphasizing the names of their collectors—endorsements that added weight to each entry.

The objects were gathered through numerous visits by Low and Moore to artists’ spaces, their meetings characterized by gracious exchanges of showing and telling. As possessions, each item had a place to call home, functioning as door stops, ashtrays, ornaments or focal points in the dwellings and studios of individuals who awaited their return. To hear their stories in entirety would take months, and my two visits to view the exhibition, while substantial in duration, felt painfully short. Thankfully, part of the fun of “Kitchen Midden” was its pronounced articulation of the kinds of things that, seemingly, all artists appreciate. I can hold prolonged visits with the things in my own room, or storage unit, that would be welcomed into this cohort: a birch-bark biting by Annabel Eyres; a cloudberry jam jar of murky holy water; smooth pebbles from Bere Point on Malcolm Island, where orcas come to rub themselves; and Group of Lunar Mountains – Ideal Lunar Landscape (1874) by James Nasmyth.

Lucien Durey is an artist and writer based in Vancouver.

Detail of Jessica Bell’s Seed Work at Unit 17. Courtesy Unit 17. Copyright the artist. Photo: Pongsakorn Yananissorn.

Detail of Jessica Bell’s Seed Work at Unit 17. Courtesy Unit 17. Copyright the artist. Photo: Pongsakorn Yananissorn.