Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.—AUDRE LORDE

My intellectual formation dates to the early 1990s, when I packed up what I had learned studying art history with Drs. Bridget Elliott and Victor Chan at the University of Alberta and toted it to New York. Whatever I thought I was going to focus on in graduate school—it had something to do with German art, even though I didn’t know a word of German—flew out the window the moment I took my first class with the late Linda Nochlin, who had recently arrived at New York University.

I didn’t at first realize who Linda was, in the grand scheme of things. All I knew was that she was a brilliant, funny and deeply charismatic figure who seemed to derive endless enjoyment from laying bare the gendered work—the violence, but also the ridiculousness—of some of the most cherished works of art history.

It was her intense capacity for pleasure in looking that distinguished her, in my mind, from the other feminist writers who loomed so large on the scene in those days. I believed Laura Mulvey, of course, when she wrote, in her 1973 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” about how visual pleasure was produced in classic Hollywood film: by leaving no room for the female viewer, by forcing women into a choice of imagining themselves the passive object of the gaze, or of identifying, at the expense of their gendered subjectivity, with the active male protagonist. To imagine that our—women’s—enjoyment of the visual field was predicated on willingly erasing ourselves was a hard, important lesson for me, and I lapped up the work of such writers as Griselda Pollock and others who extended Mulvey’s lesson to the analysis of painting. Pleasure was something to be interrogated and deconstructed, even mistrusted, not taken at face value. Not a terrible lesson to learn, given how many people in the world seem to derive their greatest enjoyment from the unhappiness of others.

At a distance of a quarter century, Mulvey’s essay seems less unimpeachable to me than it once might have. (Even she saw the limitations of her formulation, and published a retraction of sorts not long after the text appeared, but that didn’t stop generations of students and scholars from treating the essay as settled law.) It seems a curious relic of a moment when Lacanian psychoanalysis was the order of the day, and when we still believed that gender could be reduced to a mere two fixed points. I’ve no doubt, though, that Mulvey continues to shape my thinking about images in ways that I can no longer even recognize because her ideas are so ingrained, and thus invisible to me.

The audience understood completely what she meant: aesthetic pleasure was important now, not just for its own sake, but to revive us, to give us the wherewithal to fight another day.

THE WORLD—or really, my world—was much different in the early 1990s than it is now. Wars were short and dirty, except when they weren’t. (I still remember the visceral trauma of reading about the sustained program of rape perpetrated by the Bosnian Serbs against Muslim women in the wake of the breakup of Yugoslavia, my fat tears smearing the ink on the newspapers I pored over, not quite believing what I was reading.) The HIV/AIDS crisis was largely invisible to me, I’m ashamed to admit, as were many other injustices.

There were reasons for this, none of them reflecting particularly well on my engagement or my politics. I wasn’t hooked into the alternative press that was sounding the alarm about issues that the New York Times failed to cover—and in the pre-internet age, keeping informed was a much different sort of business than it is now. Plus, there was enough good news to focus on, perhaps, that I paid less attention to the bad. Apartheid was crumbling, as was the Soviet Union. We were entering the Clinton era, an era of complacency for me and many like me—middle-class, First World Gen Xers, lulled by the soft waves of prosperity ushered in by neoliberalism, largely ignorant to the harshness and injustice that subtended it. The culture wars were real, though, as were the kinds of inequalities that led to Clinton’s impeachment and, consequently, to the racist welfare bill negotiated in its wake and the (further) criminalization of Black poverty.

The irony: I was learning to look askance at the way pleasure was produced in the visual field without being at all conscious of the violence that was obscured by my political complacency.

That changed by 2001, in the aftermath of 9/11, which ushered in a period of continuous war perpetrated by the US, and by the gross, populist nationalism that poisoned any possibility of political discourse. Even Obama couldn’t save us, as much as many liberals wanted to believe he could, and in some ways (drone attacks, deportations) he committed his own geopolitical crimes. It seems important to remind ourselves that what we are experiencing in the wake of the 2016 election is a horrifying intensification of what was circulating before.

The strangeness of the Trump era, and the only aspect of it that offers me a glimmer of hope, is that it’s impossible to be unaware or unaffected by what is happening around us. To be sure, some feel the injustices more keenly than others; some of us have more resources to deploy when injustice touches us. But the privileges and entitlement that once allowed someone like me to be mostly blissfully unaware of some really horrible things happening around me? Gone.

Perhaps that’s worse: knowing that if people stand idly by at what feels like a truly apocalyptic moment, it’s not because they were blinded by privilege. It’s that they see and don’t care, or that they see and celebrate the end times of our humanity. It’s not because they have no concern for my or others’ well-being. It’s that they are cheering for our demise.

It sounds like an overstatement, I know. But I now live in a country where people in power can simultaneously celebrate the “greatest generation”—the people who fought against the Nazis—while embracing the ideals of those very same fascist foes.

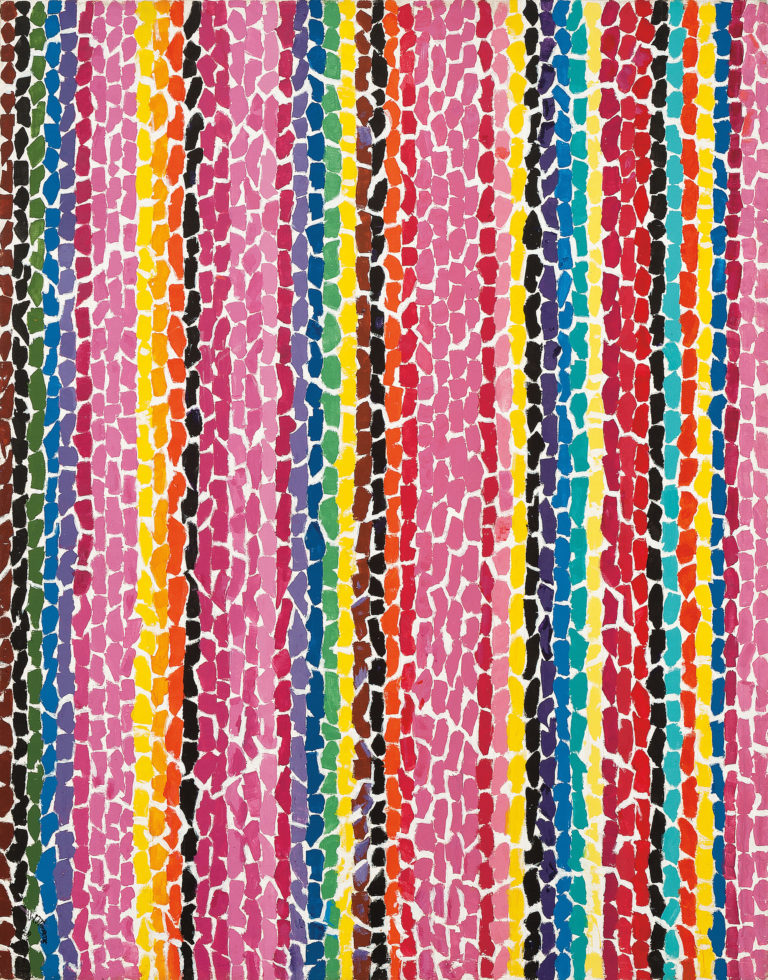

Alma Thomas, The Azaleas Sway With the Breeze, 1969. Acrylic and graphite on canvas, 1.62 x 1.27 m. Private collection. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York.

Alma Thomas, The Azaleas Sway With the Breeze, 1969. Acrylic and graphite on canvas, 1.62 x 1.27 m. Private collection. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York.

THESE ARE the thoughts that circulate in my mind as I think about my relationship to pleasure now, especially now as every day seems to bring news of the opposite. Linda Nochlin’s insistence on admitting to and revelling in the joy she took in even the most ridiculously sexist works of art seems utterly defiant in retrospect. She may have never been seduced by the sexiness of a Renoir nude per se, but I remember an epic dinner-party argument once when she declared him one of the best painters of the era due to the sheer virtuosity of his technique. (T.J. Clark backed her up.) This tendency was emphatically not the result of insensibility, or looking away: witness her standing, in late 2001, on a stage at Princeton where hundreds had gathered for a feminist conference, and issuing a dire warning that the wars the US was about to embark on would lead to a doubling down on the worst forms of toxic masculinity, of militaristic violence and of an increasing propensity to police the female body in the years to come. You could hear the gasps in the room as she laid out our future so starkly. Even more horrifying is the realization that she was not in the least wrong. No, for someone who saw so clearly, the embrace of pleasure was a necessary corrective, a rallying point even, as we confronted the evils of the world. An act of détournement in its perversity—I mean, RENOIR!

I know I’m not the only one these days who looks for pleasure when I can find it—not the easy dopamine hits that social-media clicks produce, but real, meaningful, reviving pleasure. Surely it is to be found at the heart of the struggle: nothing more fun than being at a protest, amid tens of thousands of committed, like-minded people, and revelling in the optimism and righteous outrage that propels us all forward. I am continually struck by documentary photographs of Lorraine O’Grady’s early-1980s performances of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, for which she donned a tiara and debutante’s gown made of white gloves and entered institutional spaces from which Black artists had been excluded, including, perhaps most famously, the New Museum. In a number of these images, O’Grady stands, in full regalia, with fellow artists and friends, her head thrown back in a full-throated laugh. Fierceness and pleasure are hardly incompatible.

But a respite from the struggle is no terrible thing, either—pleasure that comes for its own sake. Allowing ourselves to feel such things is the ultimate form of self-care. We live to fight another day.

Alma Thomas once said, “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.”

IN AUGUST, I moderated a conversation on abstraction at Greene Naftali Gallery in New York. The legendary African American artist and activist Howardena Pindell was on the panel, speaking of the two sides of her practice—one overtly political and combative, and the other devoted to truly beautiful abstract painting. This bifurcation had existed in her work even before what may be the artist’s best-known work—the devastating video Free, White and 21 (1980)—but it perhaps became starkest at this point. In it, she dons whiteface and, speaking directly to a camera, ventriloquizes the gaslighting and aggressions—micro and macro—she and other women in her family had experienced at the hands of white women, whose cruelty was glancing and often went unchallenged.

Free, White and 21 was made on the heels of a 1979 exhibition at Artists Space, a supposedly progressive, independent, publicly funded gallery, for which the (white) artist Donald had used the most incendiary racist epithet in the English language to title his works, while some of the most respected artists and critics of the time rallied to his defense. Pindell, along with a multiracial coalition of art-world figures, protested the show; she was ostracized by her colleagues at the Museum of Modern Art, where she worked as a curator, in the wake of her actions. The video was shown at AIR Gallery, a feminist cooperative art space, in an exhibition curated by Ana Mendieta—“Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States”—that was meant to challenge the almost exclusively white focus of the gallery and its politics. Knowing this context sheds some light on the frustration—or rather outright, barely contained, and wholly understandable anger—that emanates from the video monitor as you watch.

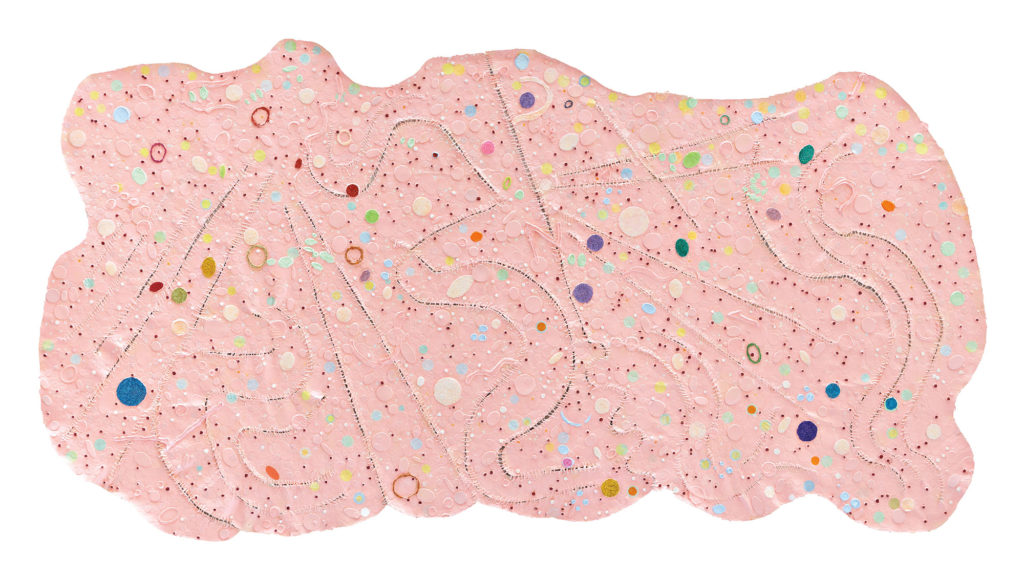

On this evening at Greene Naftali, Pindell spoke of new projects, including one particularly alarming-sounding object centred on severed hands, which reference the punishment of slaves and political dissidents. There was an audible gasp in the room when she discussed the dilemma of whether to include simulated blood. At the same time, she said, she was working on new abstract paintings, still focused on her signature use of cut-paper rounds in delicate pastel colours, collaged onto the surfaces of canvases, which sometimes incorporated glitter or perfume.

She assured the audience—charmingly, disarmingly—that these latter works were some of the most beautiful paintings she’d ever made. “I think of them as Tylenol for the Trump era,” she said with a twinkle. There was gentle laughter, along with a murmur of understanding. The audience understood completely what she meant: aesthetic pleasure was important now, not just for its own sake, but to revive us, to give us the wherewithal to fight another day.

Her words recalled, for me, the work of another Black woman who devoted herself to a deeply beautiful, non-representational, not explicitly political art practice: Alma Thomas. Thomas made abstract paintings in the middle of the Civil Rights era, while living in Washington, DC, a city roiling with racial tension and a place where millions of Black people were gathering in the 1960s to seize their right to be treated as full citizens of the country that they and their ancestors quite literally built. Her decision to eschew a representational style—and thereby to sidestep what many Black artists and writers considered an obligation for their peers, to make art that supported the struggle—marked her as an outlier. Her paintings— large, dazzlingly colourful canvases made up of saturated, blocky strokes of acrylic on white ground—were based, not on the historical events that were everywhere surrounding her, but on the visual pleasures of her garden, an oasis in the city.

Thomas once said, “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.” It would be easy to hear in her words an echo of Matisse’s infamous remark that he dreamed of making art that was “a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair” for a tired businessman: a palliative, an escape, a retreat into bourgeois complacency. But Thomas’s paintings, the art workshops she taught in neighbourhood community centres, her garden—all these taken together suggest to me, as I have previously articulated in a review of Thomas’s 2016 show at the Studio Museum in Harlem, that her paintings are, emphatically, not mere escapes. Rather, they are respites—breaks from the action, not flights from them. To my eye Thomas’s work, like Pindell’s work, and like so much of the work I am most interested in looking at right now, seems less like an apolitical retreat from the harsh realities of her political moment than an act of nurturing and care for a community stretched to its limit.

This, then, is the pleasure I seek.

Howardena Pindell, Carnival: Rio Samba School, Brazil, 2017–18. Mixed media on canvas, 104.1 cm x 2.1 m. Courtesy the artist/Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

Howardena Pindell, Carnival: Rio Samba School, Brazil, 2017–18. Mixed media on canvas, 104.1 cm x 2.1 m. Courtesy the artist/Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.